Interview: In The Studio With Eddie Peake

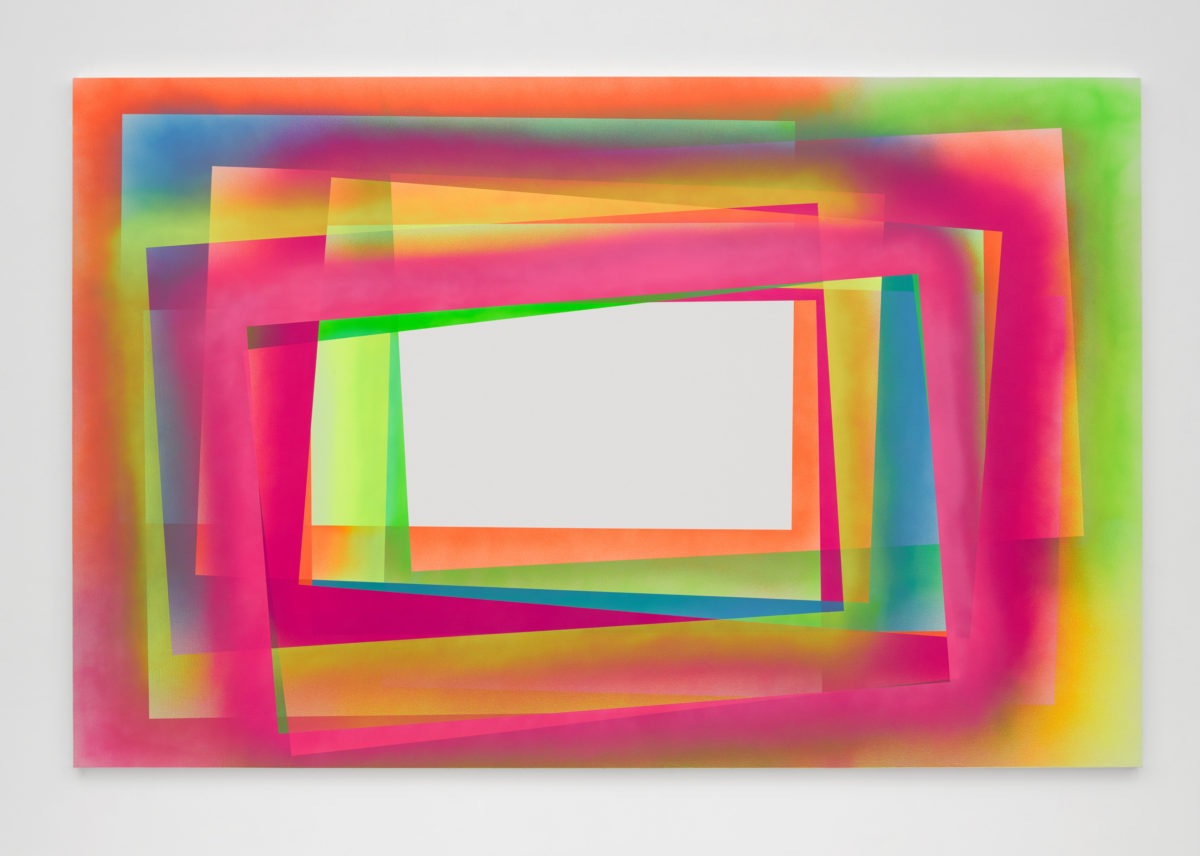

By Rachel McleanEddie Peake’s diverse artistic vocabulary encompasses performance, video, photography, painting, sculpture and installation. Peake’s central focus lies in the lapses and voids inherent in the process of translating between verbal language and nonverbal modes of communication. It is in the discrepancy between words and any other language, including, images, emotions, gestures or sounds, that his art is located. Peake’s work is an often-energetic spectacle in which the absurd and the erotic each find a place, and in which the artist plays a central role. Ahead of his upcoming exhibition, Where You Belong, opening later this month at White Cube Hong Kong, Something Curated speaks with the artist about the evolution of his work over the years and his aversion to convention.

Something Curated: What compelled you to want to become an artist at the age of seventeen?

Eddie Peake: When I was younger I wasn’t one of those people who knew from day one that I wanted to be an artist. That might be because from a young age I was exposed to contemporary art, and there are few things which can really put a young person off wanting to be a given thing more than it being something that their parents do. So it’s always something I always kind of resisted. Also, I had always wanted to do something more rewarding, because frankly being an artist is not a rewarding job. Well it can be, I am in a rare position of doing things that are quite public and I’m very supported, I am not being unappreciative of that, but for the most part it’s hard work, and thankless work, and then when it goes well you also get extremely criticised.

When I was in my late teens, I kind of hated school, I was not very good at it, well I really struggled with it; I was going to drop out, then I did drop out, then I restarted, and I was going to drop out again, and in that exact period I by accident made some paintings I really liked. I just made some paintings for an assignment at school, and, I tried something new that I hadn’t tried before. The paintings I made were big and bold, and happened quite easily for me. It was the combination of these two things, it being quite easy and enjoyable, and then resulting in something I really liked. It was kind of an epiphanic moment — I realised that you can do something you enjoy and like the results, and that’s what you should be doing with your life. That happened around the end of seventeen or eighteen.

SC: Is there a guiding narrative or ethos that connects your work?

EP: No, I wouldn’t say so. It’s quite varied. It’s more of a collection of dominant ideas.

SC: What is your daily routine like? Do you work mostly in this studio or tend to move around a lot?

EP: I try to be here in the studio as much as I can, I’m not here too often. I get here at 11, stay until 7 or 8. I’m never doing a singular thing, on some days I might come in and work with a fabricator or responding to emails.

SC: Do you feel that art school was necessary?

EP: I’ve been to four art schools in total. While at Slade I did two exchanges, one at Bezalel in Jerusalem, the other at Yale. Then there was the Royal Academy of Arts. I think going to art school is a really good thing to do, whether you like it or not, but I think you can be an artist without going to art school. I just think that it’s a really good thing to do because even if you don’t enjoy it, the level of exposure to ideas, processes, and art, frankly, is so much more intense than it is if you don’t go to art school.

SC: What projects are you currently working on?

EP: The main thing I’m working towards is the exhibition in Hong Kong, Where You Belong. It’s a solo show, and though the question around identity has always been in my work to some extent, it’s really the focus of this show. What I mean by that is that I want to be specific, it’s quite a vague, overused term. I suppose there’s an aspect of my work that has tended to invite a kind of scrutiny, often quite punitive, aggressive and judgmental about my personal life, and particularly about my personal sexuality. And whilst I’m not asking, “Why the hell is that happening?”, because there are aspects of the work that kind of invite that, it has always tended to be a kind of inquisitive line of enquiry on my part — as opposed a self-aware trickery, which is where the scrutiny mistakenly focuses on, I think.

From my point of view, I want to try with this show to tackle it a bit more head on, so there’s that, that’s one of the three main themes. It’s a sort of investigation or quest for realising one’s own identity. It’s my conviction that you arrive at the universal or the social or the political via the personal, so I don’t think it stops with being just about my own identity. Identity with specific regards to sex, sexuality, gender and desire as well. The second theme is to do with psychosis and depression, and the inner conversations that take place within one’s head. Depression specifically is an ongoing struggle that I deal with in my life; I’ve spent time in psychiatric hospitals with various kind of medications to deal with it. I don’t see these two themes I’ve mentioned so far as unconnected, if you ask someone who is struggling with psychiatric issues, how can that not impact on your sense of self in the world?

The third thing that the show relates to in my mind is looking. The role that one places as a viewer, not just in an art gallery. In the Hong Kong show there will be these photographs of a naked girl masturbating in a gallery, but I quite like that her gaze is fixed on the computer she is looking at, the porn. While she could be said to pertain to the sort of imagery most people associate with a male gaze, she’s actually in her own world of looking that is for her own gratification.

SC: Tell us about some of your projects which you are most proud of?

EP: I was really happy with my recent performance in at Jeffrey Deitch’s new gallery in New York that was entitled Head. I think it was the best performance that I’ve ever done, actually. I made it collaboratively with the performers, that’s how all of my performances are devised. So me, and in this instance, five dancers and three musicians, we have a set amount of time to create and rehearse the piece, five days I think it was. One of the people I collaborate with quite frequently, Gwilym Gold, once said that he thinks, “We find the work”, which I thought was a really apt description actually. To make something like this the whole ensemble, that is to say the musicians and dancers and I, arrive in the space, improve and workshop the shit out of it. I tend to lead those by shouting out, dictating what people should do, and they’ll tend to respond to what I’m saying. It means that 90% of the stuff we try out ends up being discarded, and then the other 10% results in the work. It’s very nerve-wracking as I never know whether it’ll result in a piece of work I like.

SC: Do you have any unfinished work you’re able to tell us about?

EP: I have tonnes of unfinished paintings and ideas, though the latter are not really unfinished; they just take a long time to come into fruition. There’s a place in my studio where I post different ideas. Sometimes I feel inspired to create something which I thought about years before. I first had the idea for the naked football match that took place at the Royal Academy of Arts, which is probably one of my most well-known pieces, 8 years before.

SC: You are often described as the most promising artist of our times. Which other contemporary artists work do you like and why?

EP: They’ve been running that article for 10 years now, in different publications and stuff. It’s quite annoying now, like chill guys, I’m really here, I’m not going away. I guess I like artists who don’t really mind putting themselves out there in a way that leaves them vulnerable — those who have the balls to leave themselves exposed. I say this because in a lot of the exhibitions I see, I feel like the artists very carefully try to closet themselves away from the world, while also exposing their work. I don’t really have much respect for that endeavour.

There are some artists that I think do that, from the past who I still think about a lot, not necessarily from my generation: David Foster Wallace, David Lynch. Basically anyone called David, I’m just joking. I like Michelangelo Pistoletto and Linda Benglis. I really like Peter Saul’s work at the moment. I think many of the artists I respond to tend to have a masterful disdain for convention and tradition. A lot of what I like is not what you’d necessarily look at and go, that is, and then in big, bright, neon-invert commas “good”. In terms of more contemporary artists I’m a fan of the work of Ericka Beckman.

SC: Nudity has always been accepted as the norm in classical sculptures, why do you think in the 21st century it is so often deemed as provocative and humorous?

EP: That’s an interesting question. I don’t know. It’s quite odd because I lived in Rome for a couple of years, and everywhere you turn there is a naked sculpture, and yet, if you want to employ nudity… I feel like we live in this weird age of conservatism in which people are desperate to find opportunities to be offended. So desperate are they in fact that they’ll even be offended by things which aren’t actually offensive.

I realise that the other side of that coin is really good, that people are questioning some of the conventions that have enabled men to dominate the world forever, and for white people to do the same. The other side to this is that artists who want to do things that interrogate or challenge a given historical precedent might be taken completely at face value for their work, rather than be seen to be questioning whatever they are portraying. This consistently happens to me and it’s really annoying. There’s this conservative assumption that nudity is being used to provoke, titillate, but really in essence, what could be more banal or mundane than using the thing that we all have at a sort of base, primal level, which is the naked human body? And that reaction to my work does sort of bore and annoy me, because my use of nudity is, I guess it’s a few different things, but on the one hand it’s these ongoing questions which relate to gender, desire sex, sexuality, and so on, and all of that is filtered through a totally self-reflective line of enquiry.

It’s not me making judgements about anyone else in the world, it’s me being quizzical about my own position in the world. And on the other hand, it’s just a simple solution to the question, let’s say we’re talking about a performance, “What is this performer going to be presented like?” And if every single thing we do has a semiotic register attached to it, then the one semiotic register I don’t mind working with is that constituted by nudity. I don’t want costumes, because up until now at least I haven’t come up with a set of costumes I would feel comfortable employing in my work.

SC: One thing that often seems to find a place in your work is the human body – why?

EP: Aside from the reasons I’ve already mentioned, regarding this enquiry into self via gender, sexuality and all that, I also really like for there to be a narrative and immersive experience for the viewer. I tend to want the viewer to feel implicated as a participant, as a protagonist and that the bodies they encounter might act as a sort of mirror. The reason I say “might”, by the way, just to be reductive and simplistic about it for a moment; there are artists who think about the work and then they make it, and then there are artists who make the work and then they think about it, and I am 100% the latter. I do teaching now and again, and I’m always amazed when talking to a student or an artist who talk and talk and talk about this work, and then I say, “Okay, let’s see it,” and they tell me they haven’t made it yet. I don’t know how you can know about your work until you’ve made it, because inevitably you do one thing to make it manifest and real in the world, and it turns out quite different to your initial expectations. I’m not saying I don’t have a vague idea prior to creating a work.

SC: How did the Forever Loop at the Barbican come about? What was the narrative for this performative installation?

EP: I was really happy with it, I have to say. To me it felt like a phenomenon. It was amazing for me that 31,000 people came to see that show, and I heard random people talking about it even on buses. So it was really exhilarating for me — not just from the perspective of, “My show is a big hit,” but I want the work to have relevance in the world. I didn’t want it to just be a finite thing that’s only entertaining. I’ve always maintained that I want to make my work for the world, not just for the art world; I don’t want it to be exclusive. I want it to be part of the conversation about being a person in the world. In terms of actual content, I wanted the show to be a totally subsuming environment that the viewer would be immersed in, and by necessity kind of implicated in our form of narrative. And when you ask, “What was the narrative?”, I wouldn’t be able to say anything specific in terms of plot movements or a specific chain of events, it’s more the feel and structure of a narrative.

SC: In previous interviews you have mentioned that you often work with other artists but don’t see the resulting work as a collaborative piece. Thinking more about the process, what was your most memorable collaboration?

EP: I often hear it used when anyone has any kind of interaction with another person, and I don’t think that is necessarily a collaboration. There have been instances where I have done performance work, where I’ve written every line and showed the performer an outright choreography from beginning to end, and then I’ve later seen them do an interview talking about a collaboration. When I explain why I don’t like it’s overly prevalent use as a term, I always use an analogy of making a soup or a sandwich — if you’re collaborating with someone on making a sandwich, where you can identify your individual and divergent practices together, I feel like that’s not collaborating. Whereas if you are making a soup, where it’s all blended together and you can’t discern who did what, the respective, different components, that’s a collaboration worth doing.

In a sense the performances that I make are made collaboratively but don’t result in collaborations, because it is ultimately my authorship. In terms of actually collaborating, it’s nice to get to a point with someone where you have such a good, intuitive understanding of one another, you don’t necessarily need to interrogate every decision that gets made. I’m at that point with a lot of the people with whom I work extensively in my performances, notably Tim Goalen and Gwilym Gold. The good thing about working with Gwilym is that we worked on each others’ projects a lot; he’s made a lot of music in my performances, and I’ve made music videos for his solos. Tim Goalen who is an old friend, he writes scores for TV shows and film, but he also works with me on music and sound projects, be it playing guitar in a performance or producing a track I’m releasing on my record label.

SC: In a previous interview you said that through your art you want to create a language that is untranslatable, but that somehow communicates what you’re feeling in a language words can’t. It seems you use this language for personal reflection rather than communication. What do you want your viewers to feel or learn while experiencing your work?

EP: I suddenly can’t remember anything I’ve ever done in my career. It’s very difficult to say what I want the audience to take from it, for one thing I want the work to be enjoyed, but in terms of meaningful content, it extends to that thing I was saying about arriving at the social, political or universal via the personal. So I hope that it relates to questions that affect everyone, about who they are in the world. At the same time, I don’t know whether the work is about anything, it is whatever it is. So when I say that I want to arrive at a language that isn’t equivalent to verbal language, the very fact of trying to articulate what I mean by that negates that endeavour. But what I mean by that, is that I think there are some experiences which are very poignant, and can affect your life, which don’t happen via language — they are transcendent of language.

SC: You have described yourself in the past as shy – how do you consolidate this with the centrality of yourself in your work?

EP: Really, I don’t feel like there’s any reason not to do something because you are shy. I know what you’re saying, how can you reconcile being shy and putting yourself out there, often nude — totally counterintuitive, but the good thing about art is you mediate your impulse and the resulting art comes from a making process. Even if it’s a photo of me with my genitals out, it’s not the same as me standing in a room in front of 10 people and entertaining them. I remember once being told by a friend, if there’s ever anything you feel nervous about or not able to do, “Just pretend”, and I actually follow that advice. There’s work I want to make, and I don’t want to allow shyness to get in the way of that, just as there’s certain art that requires a certain skill set, and I don’t want my lacking that skill set to prevent me from doing it, so I’ll find a way. Perhaps I want to make the kind of work I want to make because I am shy and insecure.

SC: What’s next?

EP: Nothing solid set in stone, but there are some film and video-related projects, and some other exhibitions. The only thing I can discuss is the upcoming show in Hong Kong, which I’m really excited about. It’s the first solo show I’ll have done since the Barbican show, and the reason why that is significant for me is that the Barbican show happened 10 years after my first exhibition. Though it didn’t sink in immediately, I later realised that the Barbican show was the most extreme iteration of what I was trying to do with all my exhibitions up until that point. So for me it felt like it was the opportunity to move on from all those things I was trying to do. It felt like the end of the first chapter. Now I feel like I’m at the beginning of the second chapter, and the Hong Kong show is the first iteration of that.

SC: What’s changed between these two chapters?

EP: It would be very difficult for me to answer that. I don’t know, as the show hasn’t happened yet. I think there’s a more direct, visually direct iteration of some of the questions that I’ve been talking about, to do with mental health and psychosis and depression, but also in terms of an enquiry into identity through sexuality and gender. And how people feel about those sort of things. These themes have always been in my work, but they’ve been enshrouded in layers that make the way of accessing those things indirect. I want this next chapter to be more direct.

SC: On Rome …

EP: I lived there for two years, and during the first year, I really struggled with it actually, as it so defiantly and fervently tries to maintain its historical traditions — and if you’re maverick, and unconventional as I am, that’s quite a problem. I hope you’re able to convey my ironic and implicitly self-deprecating nuance of that joke I just made. I ultimately came to appreciate that about Rome; I like that to an extent it is away from the frantic pursuit of newness that goes on in places like New York and London. Rome offers me a place to be a bit more contemplative and slower paced about just being a person, let alone making art. I work with a gallery in Rome, and I’ve done three exhibitions with them, Lorcan O’Neill. Two of the exhibitions I made when I lived there, and one while I was living in London.

SC: Which area in London do you live?

EP: I currently live in Dalston, but I’m just about to move to Mile End. I’m from Finsbury Park, that’s where I was born and raised.

SC: What drew you to this area and what does London offer you as an artist?

EP: Dalston is nice and I enjoy living there, but it does leave a bit of a sour taste in my mouth because of its very rapid gentrification which has quite severely damaged certain communities that have been there for a very long time. I don’t know the area around Mile End too well yet but I do like it – I guess I’ll soon find out. In London there is a predisposed and enthusiastic audience for contemporary art. While living in Rome I found that there was not only not that, but also a resistance to contemporary art. Both have different challenges. In London there is a much more critical dialogue to my work, in Rome people aren’t always particularly inclined to respond beyond saying they don’t like it. While on one hand it feels sort of futile to produce work in Rome, it’s also a really great place to test how important being an artist is to you.

SC: Preferred work attire?

EP: I really like wearing tracksuits whether I’m working or not. When I’m devising performances I like to be in something I can move around in.

SC: Favourite place to shop in London?

EP: I like buying vinyl records – Phonica Records in Soho, Sounds of the Universe that’s also in Soho, and Kristina Records in Dalston.

SC: Favourite restaurant?

EP: Nando’s.

SC: Favourite holiday destination or where would you live if not London?

EP: I don’t really take that many holidays. I like going to Rome and Italy in general, but a lot of the time I go to Italy it doesn’t feel like a holiday at this point, but rather life.

SC: One golden piece of advice to aspiring artists?

EP: If you have an idea of what you want to do and you haven’t been presented with an opportunity by anyone, create it for yourself. When I left art school in 2006 I wanted to exhibit my own work, but there were no opportunities, so me and my friends did shows on our own. I built a substantial body of work from our DIY galleries and worked so hard to get where I am now.

Interview by Elizabeth Sulis Gear | Photography by Michael Vince Kim