Utility Chic: Luxury’s Fascination With Workwear

By Something CuratedUtility is chic

Utility wear in contemporary fashion can be used to describe anything from a pair of dungarees to a French workman’s jacket. Examining the intersection between workwear and fashion, this feature considers the trades of chefs and fishermen to explore the appeal of utilitarian clothing in the luxury market.

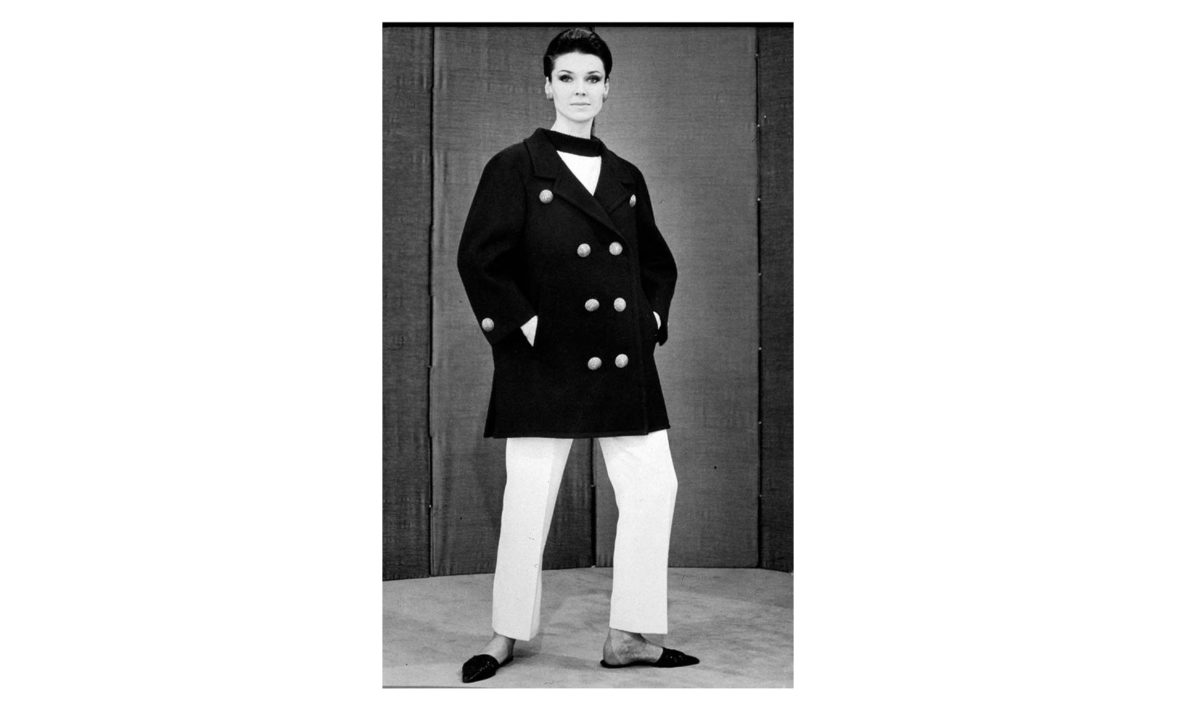

Yves Saint Laurent’s appropriation of the fisherman’s pea-coat in 1962 is one example of the re-imagining of basic workwear. It is clear that there has always been general interest when ‘honest clothing’ has the potential to be offered up as ‘luxe wear’ to consumers as fashion. In urban areas, a worker’s uniform takes on a different meaning, and there are as many street-style blogs devoted to those wearing a beanie and French work-man’s jacket in faded blue as they are to more extreme fashions. Functionality of the garments and the importance of textiles have been constantly referenced. So what is its appeal?

Is a working uniform ever fashionable?

Chefs and fisherman have been plying their trade for centuries and they have to wear a uniform to perform said labours. Chef’s clothing has been less obviously appropriated by designers and their uniform would be unlikely mistaken for anything else. Yet food has never been more fashionable in our culture, with many chefs now considered celebrities; the expression ‘food porn’ has become part of our vernacular. Chef’s clothing is familiar: a white shift, baggy checked trousers and clogs. Taken out of its food environment and placed in an urban context such as a gallery launch or an opening night at the theatre and they become something new.

Japanese fashion designer Rei Kawakubo often references the aesthetic of working clothes or uniforms to create her collections. A stroll through the Commes des Garcon domain that is Dover Street Market in London displays what looks like workmen jackets rendered in black or navy wool with little or no embellishment, yet they cost probably ten times more than a jacket from Denny’s Uniforms in Soho. In 1997 Kawakobu created Body Meets Dress, Dress Meets Body, also known as the ‘lumps and bumps’ collection. It featured models wearing clothes that were padded with lumps and bumps, thereby challenging the notion of the perfect body and emphasising the beauty of the female form with exaggerated bottoms and bosoms. This series led to a commission to create the costumes for the choreographer Merce Cunningham for his ballet, entitled Scenario. Dancers wore tightly fitted clothing in large checks and stripes which incorporated padded lumps and bumps yet these clothes did not restrict the grace and agility of dance. Kawakobu is notoriously private and rarely, if ever, discusses her process, yet this collection appeared reminiscent of a chef’s uniform. It was not simply the checked material that unwittingly referenced a cook’s trousers, but observing the performers duck and dive, they were reminiscent of the choreography evident in a busy kitchen, when chefs execute their own fluid form of dance to cope with the labours of service.

Blue is the colour

The colour navy has been worn in the fishing trade for hundreds of years and indeed the navy jumper is practically a uniform for male fashion designers. This same colour is a recurring theme in fashionable work-wear and has long been championed by those lovers of black. Coco Chanel was a pioneer of taking the aesthetic of working clothes and elevating them and among her first designs were those inspired by the wide-legged trousers and striped tops worn by fishermen in the 1920’s.

Function and authenticity

The point is that working clothes have a very particular function. Break down a chef’s uniform or that of a fisherman and every element has a purpose. Chef’s trousers don’t have zips because they get too hot in the kitchen; fishermen wear thick jumpers knitted with 5-ply wool which repels the water and unlike a chef’s trousers, buttons are superfluous because they’d get caught up in the ropes and lines on a boat.

Many fashion designers appeal to consumers by evoking “authentic” clothing. Authenticity could be reflected in a jumpsuit designed by Maria Grazia Chiuri at Dior, which resembles that worn by a garage mechanic. While the wearer may wish to invite admiration for their apparent commitment to such labours with the ersatz worker’s dungarees and aprons they wear to perform them, they may also invite ridicule because said clothes, such as the aforementioned jumpsuit, which was part of Dior’s A/W 2017 collection, would be unsuitable for their intended trade.

Contemporary work-wear designers

For 40 years the fashion designer Margaret Howell has chosen the workwear aesthetic to create her brand identity. Her understated designs convey a commitment to quality and longevity and a seeming reluctance to bow to the whims of fashion. Her clothing strongly references vintage workwear and possesses a powerful nostalgia. She has stated that the starting point for her designs was the purchase of a striped cotton shirt in a jumble sale in 1970: not only was it the quality of the shirt, the 200 thread count and its softness and simplicity that appealed, but it also reminded her strongly of the clothes her mother used to make for her when she was younger and the ones she used to make for herself.

Fabric quality and feel are crucial to her and the softness of cashmere is as appealing as the tough texture of a cotton drill apron. In a recent interview with the author, the actor Maxine Peak, cited her grandfather’s brogues and a number of garments designed by Howell as favourites in her wardrobe. Her view that these classic designs never went out of fashion and her method of looking more feminine or indeed fashionable was simply to wear red lipstick.

Old Town Clothing in Norfolk, whose strapline is ‘plain clothes made simple’ is the brand which is cited more than any other in reference to contemporary work-wear. It offers a bespoke service to create garments which are directly inspired by working clothes and materials. For example, the Jaywick Smock and Dress can be made in drill cotton or denim, and should you desire a pair of Stovepipe Trousers, they too can be rendered in moleskin or corduroy. This no frills approach to a demi-couture design has a cult following, worn by actors, such as Maxine Peak to fashion curators including Judith Clark at the London College of Fashion.

Habitus

The East End of London is now a common environment in which to see such luxury working clothes. This once largely working-class area has become a sprawling, contradictory mass. In 1900 Britain’s first ever housing estate, The Boundary Estate, north of the city, was established for the working classes whose professions included labourers and journeymen and seamstresses. Over 100 years later this area has become one colonised by a different kind of labourer; brewers, coffee baristas and fashion designers. It is a location where the original working class function no longer bears the same relevance and the social space means something entirely different. It is worth noting that many of the stores which sell ‘work wear’ display them in surroundings that echo the working aesthetic. Dover Street Market favours simple clothing rails and muslin curtains and Margaret Howell’s store in London’s Wigmore Street is a paean to bleached wood, enamel pots and Windsor chairs.

Modern occupations

Changes in fashion are reflected in changes in occupation. Coding, not banking is where the money is and a suit is superfluous when coffee shops have become offices. Trainers are not just for exercise and menus are ‘curated.’ A pair of dungarees made from Japanese denim worn in the East End is a more likely indicator that the wearer is an art director rather than a plumber. Is it this association with labour and nostalgia that makes fashionable workwear appear more meaningful or simply clever marketing by luxury workwear brands? We are living in an age when authenticity has become a buzzword and some of the most popular television shows demonstrate the ’traditional’ craft values of baking and dress-making. Perhaps the fascination is rooted in a desire to project a different set of values, when sartorial decisions were simpler and following fashion was less of a priority.

Words by Belinda Naylor | Feature image: Margaret Howell A/W13 research (via Styleforum)

Listen to When Women Wore the Trousers