Interview: Frances Corner OBE, Head Of LCF & Pro Vice-Chancellor Of UAL

By Something CuratedHead of London College of Fashion and Pro Vice-Chancellor of University of the Arts London, Frances Corner OBE has over two decades of experience within the higher education sector. Publishing widely on art and design education, in 2014, she launched her first book entitled Why Fashion Matters. Named a London Leader for Sustainability, Corner champions the use of fashion as an agent for innovation and change, particularly in the areas of sustainability, health and wellbeing. Among other positions, Corner sits on the British Fashion Council Industry Advisory Board; she is Chair of the International Foundation of Fashion Technology Institutes, and a Trustee of The Wallace Collection. Something Curated met with Corner to learn more about her work and her thoughts on mounting changes in the fashion industry.

Something Curated: Could you tell us a little about your roles as Head of London College of Fashion and Pro Vice-Chancellor of University of the Arts London?

Frances Corner: I’m the head of London College of Fashion; we have around 5500 students, from undergraduate through to postgraduate level. We have very strong industry relationships, strong research, as well as a focus on craft and technology. We have the obvious areas like womenswear and menswear but also courses such as BA Fashion Marketing, BA Fashion Illustration, BA Creative Direction for Fashion and MA Fashion Media Production. We have researchers working at the university helping students to strive in different disciplines within fashion. And for UAL, as a senior leader, I’m responsible for a number of initiatives, in particular, developing ideas for digital progress.

SC: You describe yourself as a fashion activist – could you expand on what it is you mean by this?

FC: Throughout my time at the college I have been trying to show that fashion is more than frocks and that it in fact has major implications with regards to our environment. For example, its use of water, the disposal of dye material and its contribution to landfill, can be very damaging. There are also significant ethical issues involving the treatment of garment workers, and the lack of transparency in supply chains.

The fact that the industry is worth almost $3 trillion, employs 57 million people worldwide, 80% of whom are women, makes it hugely important. So I want to make people understand the cultural, social and economic implications of this massive industry. In the end it’s something that makes many people feel good and the fact is, we all have to wear clothes. That’s why we encourage our students and our researchers to think about fashion in new ways and find the solutions to the negative issues that the industry possesses.

SC: How does fashion affect everyone?

FC: We all must wear clothes. It’s not always about following a trend, it’s also about being aware of good design, knowing how some things are made and developing your own approach to how you wear clothes. One of the things that is quite tricky at times is the casualisation of fashion, which means we don’t value clothes in the way we used to. We have more disposable income, we buy a whole range of things, and because of this clothing has become less valued. Fashion used to be one of the ways in which we could express ourselves and what was once important to us culturally has been somewhat marginalised. Because of this, I’m quite keen that we get people to understand more about clothes, fashion and good design, along with all these different subcultures attached to it – it’s really important and something that we should be celebrating and thinking about.

SC: You’ve stated, “Fashion can be art but it is always business.” How do you feel this relates to the ethos of fashion education?

FC: It’s important whilst someone is at college that they push their ideas to the extreme, as far as they will go, because they don’t know what they could potentially be creating and what they are creatively capable of. Afterwards, when you graduate, you will have to moderate your thinking and output because, at the end of the day, you will be working for a business and you are there to serve a function. For example, you can look at the work of McQueen and it can be argued that it is a work of art. However, he considered the idea that people are going to want to wear his clothes, people are going to want to buy it; it’s not just a work of art.

SC: What research projects are you currently involved with?

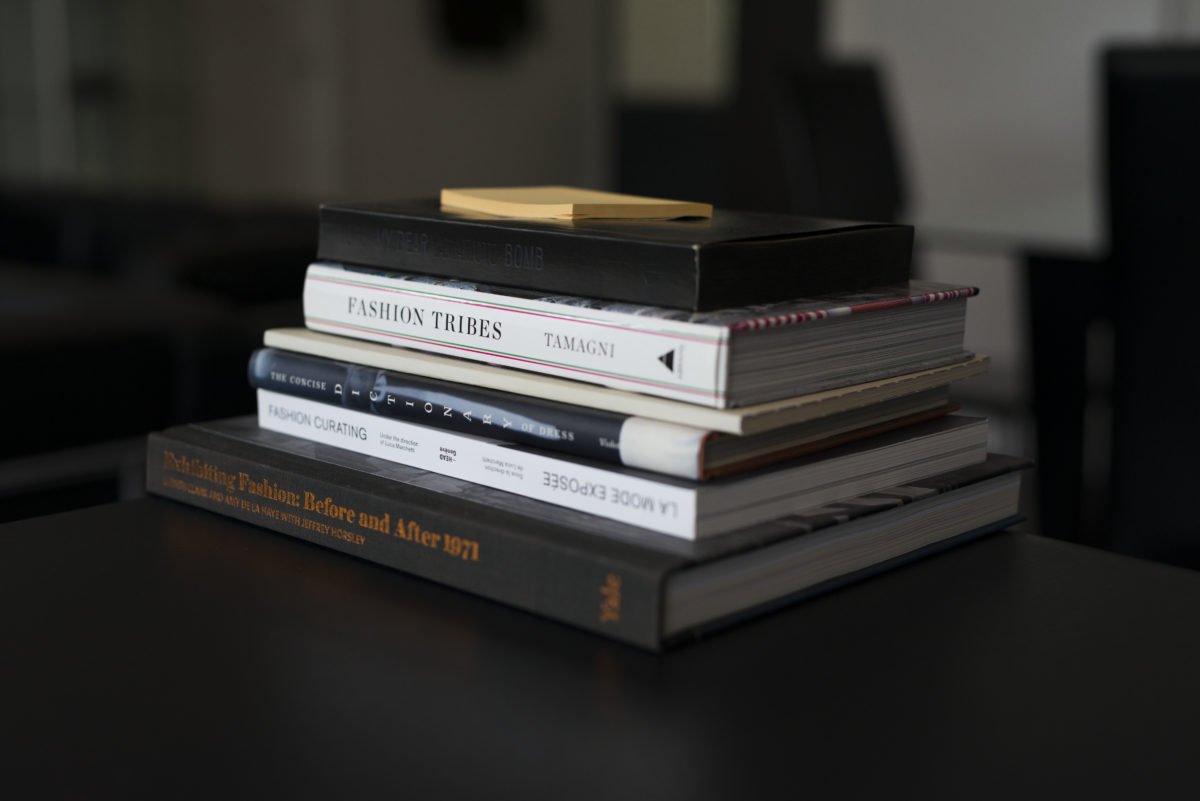

FC: For example, we have the Centre for Fashion Curation, where we have Professor Amy de la Haye working on Gluck: Art & Identity, an exhibition about the 20th century artist, at the Brighton Museum. Professor Judith Clark has just had a major exhibition, The Vulgar, on at the Barbican. We also have exhibitions in our own Fashion Space Gallery that again look at fashion in different ways, exploring clothing and how it’s presented in museums and galleries. We do a whole range of research projects with regards to the sustainability of fashion at our Centre for Sustainable Fashion and research issues like the amount of water that’s used in not only the creating of garments, but also their everyday maintenance. We also have a number of world leading cultural theorists like Professor Reina Lewis who explores the relationship between fashion and faith.

SC: How do you feel the fashion industry has changed over the past decade and do you recognise any key shifts?

FC: Obviously online retailing has completely changed the way that fashion is being sold. Platforms like ASOS and Net-a-Porter are major developments that have brought about the change. Also, the notion that it’s now possible to have a global reach without having a physical shop is a huge change. As I mentioned before, in regards to sustainability issues, people are far more aware of the subject now than they were 10 years ago.

SC: Do you find there is a relationship between these changes in the industry and fashion academia?

FC: Yes, I think that fashion academia isn’t a theoretical subject, it’s a practical one, and industry is always closely involved with that. I describe the college as having one foot in industry and one foot in education. Fashion courses worldwide have a real focus on industry.

SC: There seems to be a wider appetite for graduate collections in recent years – why do you think that is?

FC: Yes, I think that’s true, especially in London where we have such a long history of fashion education and art schools. I think there is a real interest in looking at things that are new and what’s the latest thinking. Also, London in particular has a longstanding and close relationship with street fashion, and there will always be an interest in the thinking behind that. Students get taught about how to grow a business or a fashion enterprise because it’s one thing creating a graduate collection, but it’s another thing learning how to sustain that year on year. Students come to us with their ideas and vision, and it’s our job to help nurture them.

SC: Do you have any personal favourite London designers?

FC: I wear Yohji – that’s my thing. In terms of ones to watch, with menswear, I really love Charles Jeffrey. I think J.W. Anderson, who’s a graduate from LCF, is amazing in his ability to work both at Loewe and also produce his own lines, whilst curating the exhibition at Hepworth Wakefield. It’s interesting to watch how these British designers are really building their names and their futures.

SC: You were named a London Leader for Sustainability in 2009 – how do you believe fashion is tackling issues of sustainability, and what do you think can be done?

FC: I can see how we are embedding these concerns into the college and all of our students. At the moment, we have numerous projects looking into it, and I feel that focusing on the supply chain, teaching our graduate buyers about the ways things are produced and their impact on the environment is critical. Our biggest power at the college is to really think about those issues and enthuse our students to make it a real part of their career within fashion.

SC: Could you tell us more about the London College of Fashion’s collaboration with UN Trust Fund to End Violence Against Women and Girls?

FC: We developed the Orange Label, designed by students, which could then be used by companies that would use it to sell their goods with a percentage of the money going to the UN Trust Fund. We are also helping some people at Zaatari refugee camp in Jordan by supporting some of the women to set up their own beauty business, to gain independence. We have to be aware of these issues; there are creative things we can all do to empower women and girls to have a brighter future. Education is key to that.

SC: What inspired you to write your book Why Fashion Matters – and is there another book on the way?

FC: Yes, I’m working on something around the future of fashion, drawing together some of the ideas that I’ve mentioned, investigating technology and social enterprises in fashion. I am looking at the innovative people who are showing how fashion can play an important part in society, the economy and our planet, and inviting them to write their ideas down, to hopefully include in the book.

SC: Where do you live in London and what drew you to the area?

FC: I don’t live full-time in London. I work in Oxford Circus and I have a base in Stratford. We will be moving the college there in the next five years; it will be a massive project and will connect our institution to the V&A, Sadler’s Wells and UCL.

SC: Where do you look for inspiration in London?

FC: One source of inspiration for me is people watching on the street. I also like to visit galleries. Looking at art and not just fashion is really important to me.

Interview by Keshav Anand | Photography by Michelle Marshall