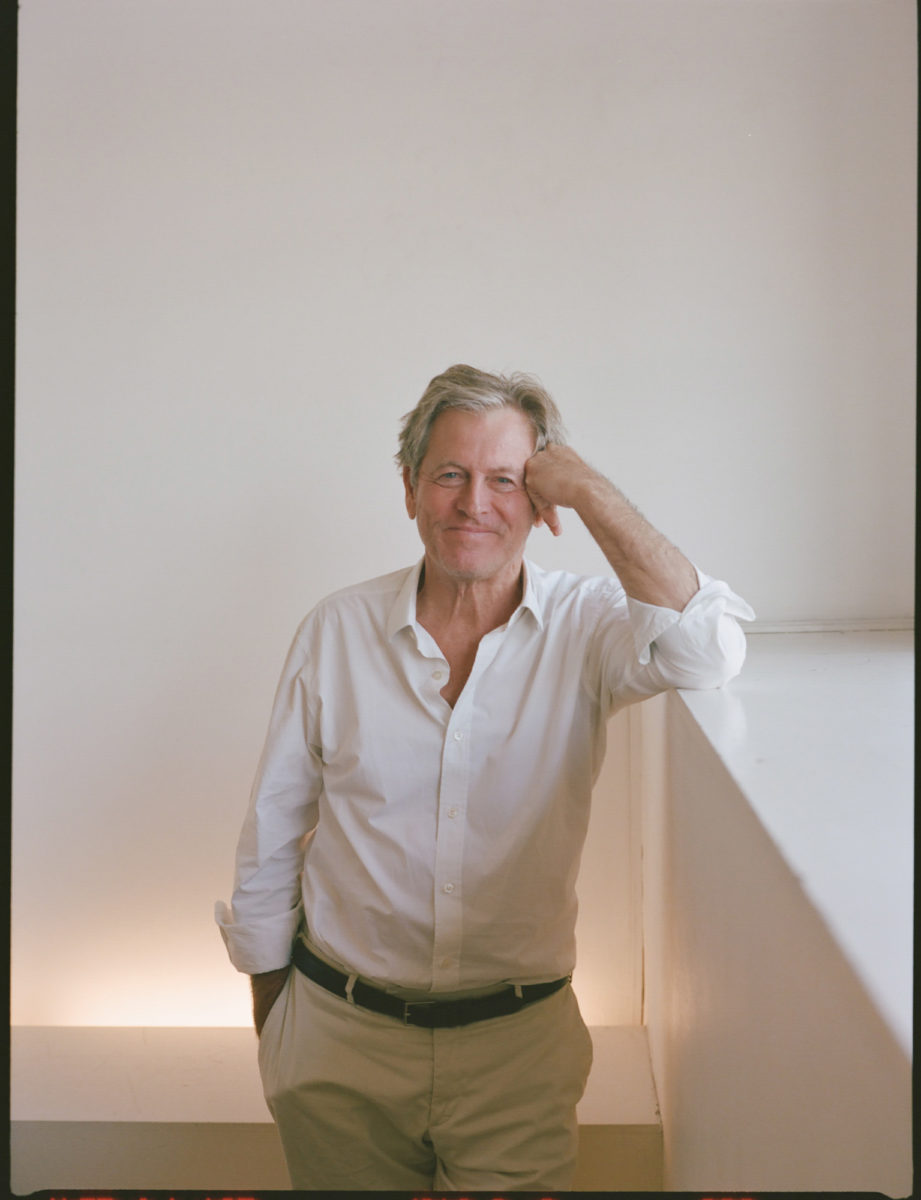

Interview: John Pawson On His Illustrious Career & ‘Spectrum’

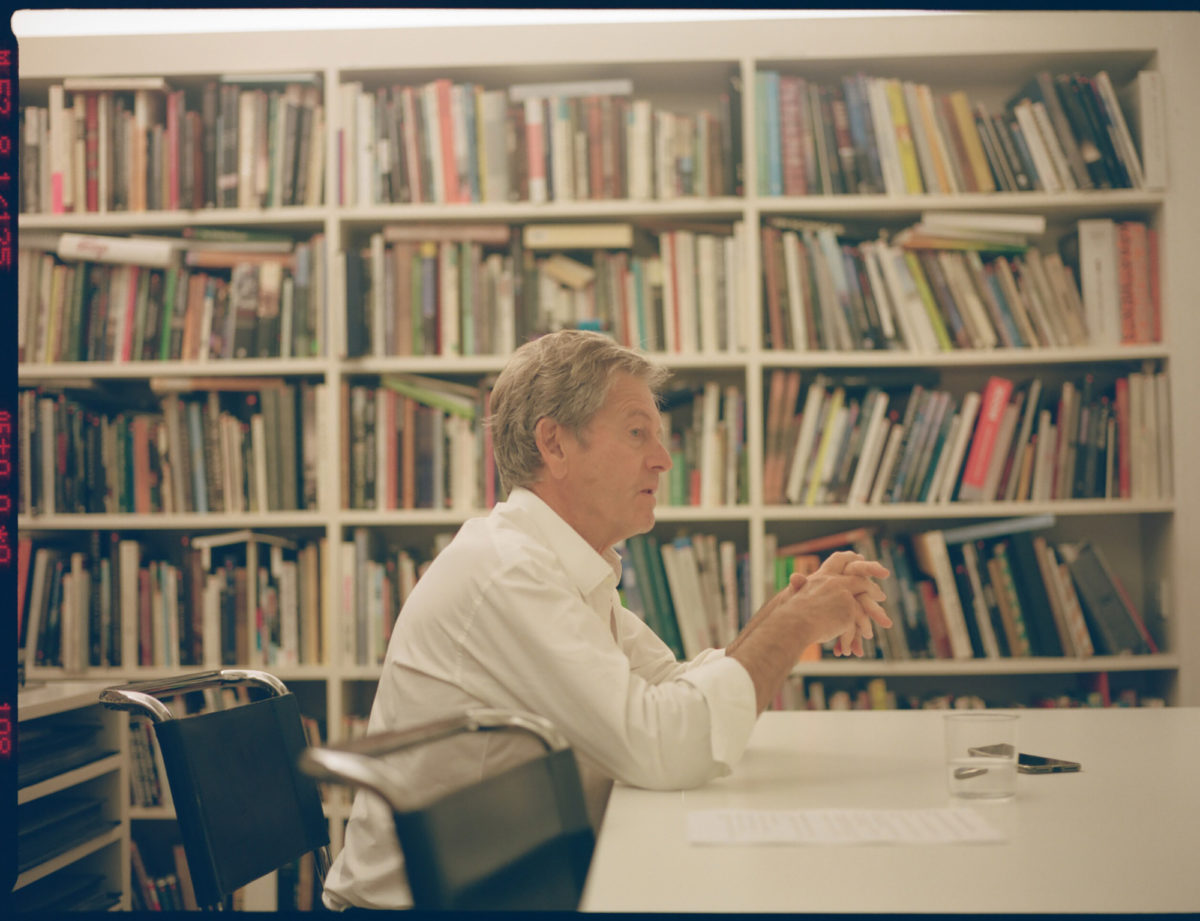

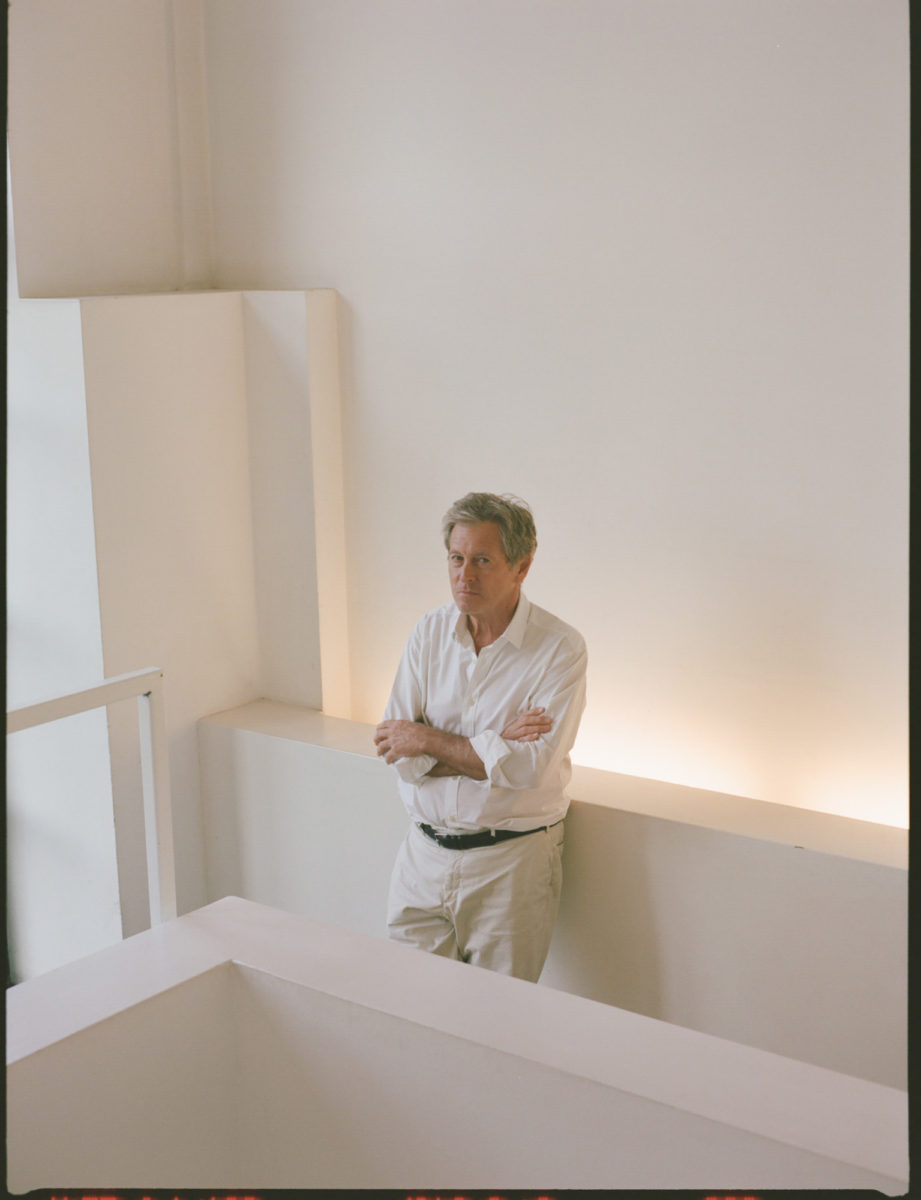

By Keshav AnandCelebrated architect and designer, John Pawson’s prolific practice spans homes, religious buildings, galleries and retail spaces all over the world, including the Nový Dvůr Monastery, a number of Calvin Klein stores, ballet sets, and London’s new Design Museum. His work distinctively “focuses on ways of approaching fundamental problems of space, proportion, light and materials.” Leading up to the launch of his latest book on 13 November 2017 – Spectrum, an unexpected ode to colour from a man whose love of white is well-documented – Something Curated met with Pawson at his King’s Cross office to learn more about his life and career.

Something Curated: Can you give us some insight into your background; how did you enter the field of architecture?

John Pawson: I was born in Halifax, Yorkshire and I always wanted to do architecture when I was at school. You know how they are at school, they said, “Well you can’t do architecture, you’ve got to do maths and you’ve got to read more books.” My father had a family business, making clothes and textiles, and he was keen that I should go into it too, so it took a long time. I worked for him for six years; it didn’t work. I was designing, but it wasn’t my thing, and then I was going to get married and that didn’t work out either so I ended up escaping to Japan and I think it was there that I had time to realise that I should follow my instincts.

SC: Broadly speaking, how would you say your practice has evolved over time?

JP: I suppose what has changed is the scale and the diversity of the work. I mean in England in the mid 70s and early 80s there wasn’t as much chance to do new building work; building houses in London or in England wasn’t the norm like it is now and so I tended to do mostly interior things, and sort of anything that was interesting, and for me that was always architecture. So whether it’s designing a cook pot or a monastery complex, which is essentially a small city, it’s the same approach. Today the office is bigger and there is a broader spectrum of work, from bridges and boats to ballets.

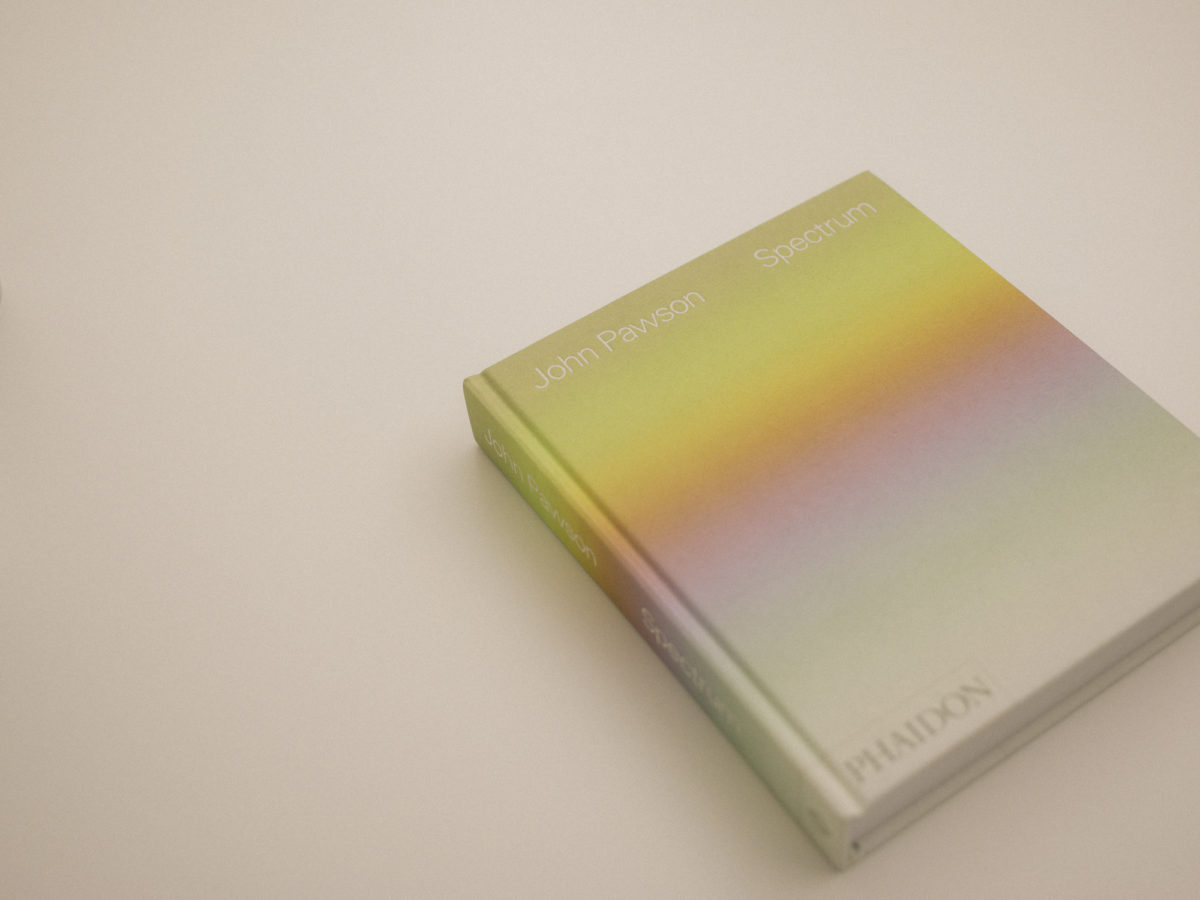

SC: What is the thinking behind your forthcoming book, Spectrum?

JP: I’ve always used photography as a tool; my sketches are very cartoon-like. The office keeps them as a sort of prized thing, but I think quietly it’s for the humour of them. I find using photography to be an easier tool than sketching and it’s a way of documenting. It retains a unique moment; each time I see something, I try and record it because it will never happen again exactly like that. I took them as a tool but then people seem to like the photographs that I did so we made this book. Phaidon knew about my pictures and they had the idea to order them by colour. I think they were surprised my photographs covered such a diverse spectrum. I mean you cannot escape colour, unless you’re colour-blind or have a condition.

SC: You are often described as a champion of minimalism – was there a moment when you discovered the aesthetic or was it always part of your taste?

JP: When I look back, there were sort of moments. I tell the story: I went on a school outing when I was six and I was very proud of these Parker pens; I had the arrows in my breast pocket. I went on the trampoline and they came out and I lost them on the beach in Blackpool; I was very upset on the bus home and I realised then that I should not get attached to material things and it’s crazy to behave as if I’d lost something important, like a human being. I was much happier after that. We lived in a comfortable house but in my room I never had anything, just a single bed. Both my parents were Methodists and I think that non-conformist, no adornment kind of life and church had some influence.

I wouldn’t say I was a champion of minimalism; it’s always what seems to make sense for me personally and it’s been very good for me that other people are drawn to it as well. When I started in England in the late 70s, early 80s people said things like, “You were in China, weren’t you?” Because they thought China and Japan were the same thing. It was extraordinary to me that they thought what I was doing was mad; they thought I was odd.

SC: I understand before architecture you had intentions of becoming a monk?

JP: As I said, my mother was a Methodist, and my grandparents were primitive Methodists, so I think she always felt slightly uncomfortable with money and her background, and she wanted me to be a modest missionary, unaccredited in Africa or something. My idea was to be a Zen Buddhist monk, and to achieve enlightenment in the best monastery in Japan. I remember seeing this documentary on an Eihei-ji monastery where these Buddhist monks were practicing martial arts as a discipline and I thought, “Oh, that’s for me.” I mean I was 24, I might as well have been 12; I had this schoolboy idea. My friend dropped me off at 6am and picked me up at 6pm, so I ended up spending 12 hours there rather than 12 years.

SC: What in your opinion is one of the best-completed architectural projects of the last decade and why?

JP: It’s not that I’m not interested or not aware but my head is so much focussed on what I’m trying to do. My interests span a thousand years, so it wouldn’t be a building in the last decade. I like Le Thoronet monastery but that’s 12th century. I like Louis Khan as a 20th century architect. I’m not a great one for the new.

SC: Could you talk to us a bit about your experience working on St Moritz Church?

JP: Helmut, the priest of the church, had seen the work I had done in the monastery in the Czech Republic, and wanted to steer his committee to using me to refurbish the St Moritz building. It’s interesting because it was bombed by the British; it was a baroque church, quite spectacular, and after the war it was rebuilt as kind of modernist. They restored the shape of it but it was quite simple. It was a funny thing for a Brit to be working on a church that was bombed by the British – it was a nice thing.

SC: Are there any particular materials or types of spaces that you are currently enjoying working with?

JP: Not that it’s in any way the biggest but the farm I’m converting in Oxfordshire for the family has been preoccupying me for the last three years. We are lucky to have a very nice house in London but I did that 20 years ago; it’s interesting working on something for the family at a different stage. It’s a 17th and 18th century set of buildings with some land – it’s been a fascinating process of taking what’s there, learning from it, knowing deeply about the history and transforming it into something for the 21st century. It’s so long that I had to put a kitchen on either end, because its 50 meters from one end to the other, so you’re never far from a coffee.

SC: Could you talk to us about your approach when conceiving the Design Museum; what were you aiming to conceptually and practically achieve with the project?

JP: In London you have to deal with what you have and it was an extraordinary building in the first place. A lot of things go on apart from just the exhibitions, and these needed to be accommodated. It’s very difficult when you are deciding something for churches, as they are public buildings in the way that they are accessible, but not on the same scale as the Design Museum, which has almost a million visitors in a year. I mean, that is completely different, that is the public, that is a huge cross section of people, tastes and opinions.

You cannot please all million visitors; people said, “Oh, the public space is too big, the place is too small, there is not enough exhibition space,” and you are like, “Hey, you know, just enjoy it.” It’s in the middle of the park, it’s an extraordinary place, it’s near where I live too, so I love it. It’s amazing for London to have, on top of everything else that it’s got, a museum with an extraordinary programme of design exhibitions. We’ve got fine art and other things, and of course we’ve got the V&A, but to have this as well is great.

SC: Could you talk to us about your decade-long working relationship with Calvin Klein?

JP: I met Calvin in 1993. He had asked Ian Schrager for recommendations of young architects around the world and Ian gave him a small book of my work, and he looked me up when he came to London. It was an odd thing because I was in sort of an irritable mood after a bad meeting, and I’d had a couple glasses of wine at lunch, came back to the office and lay down. They told me, “Calvin Klein called” and I said, “Fuck off, I’m going back to sleep.” Then they said, “It was Calvin Klein himself on the phone for you.” Anyway, he said, “I really love what I have seen of your work, can we meet up?” and I said, “Sure,” and he replied, “Well is it fine right now, because I’m outside in the car?”

It’s a bit difficult to imagine now but I had seen him everyday in the paper, because of Studio 54 and the advertising. He was one of the highest profile names in the industry, so it was so surreal. Anyway, we seemed to get on and I think he would’ve liked to have been an architect. It was an interesting collaboration. It was a balance, trying to explain that you can’t always do things in architecture like in fashion, but nothing was impossible for Calvin. If he wanted something he would say, “What about this cortex steel?” and I’d say, “Well, I don’t think it’s really appropriate,” and he would just say, “Get Richard Serra on the phone …” Nothing was impossible.

SC: What are you currently working on?

JP: We’re doing some houses, we’re doing some religious things and we’re finishing two hotels next year, one is in West Hollywood for Ian Schrager. Being able to produce a temporary home for people is fascinating if you can get involved with everything. But I also like designing tiny things, a collection of stuff for the home. There are plenty of nice glasses and carafes but I quite like seeing my own on the table.

SC: Light plays a vital role in your projects – could you expand on this?

JP: There is no architecture without light – I think that was Louis Khan. It is the single most important thing. With white neutral spaces, if you’ve got light coming into the space, you can get a huge range of colour that changes all the time, so I don’t feel you need to artificially introduce colour.

SC: As well as public and commercial buildings, you have worked on numerous private homes – creatively speaking, do you find one to offer more freedom?

JP: Each project is very different. When I started out, my contemporaries were saying how impossible it was to do private houses because they were so complex and yet so financially unrewarding, because there just wasn’t the fee to cover things, and I never really understood that. I mean I could understand the money side but for me I find homes infinitely fascinating, the way people live, and you spend so much time in them, but I wouldn’t want to just do one thing. I’m always tempted by new things. I don’t know what’s coming but to have done a bridge, a boat, a ballet, even to do a book, is very satisfying.

SC: What was the narrative behind the set you created for Wayne McGregor’s Chroma at the Royal Opera House?

JP: The set had infinite possibilities because it was so simple. The inspiration came from the church at the Cistercian monastery I designed in the Czech Republic. The apse at Nový Dvůr is a white curve rising uninterrupted for over 16 metres, with a concealed void that produces a series of ethereal effects of light. You’re not quite sure what you are looking at and that’s what I wanted to achieve in the ballet too. I did a few sketches and Mark Treharne from the office made it happen. Lucy Carter, the lighting designer, was able to use light to change every scene.

SC: What attracted you to King’s Cross?

JP: I moved here in the 90s because it was cheap. We realised that its incredibly convenient transport wise for people working here; I mean if we moved they would have one extra stop wherever they were. It was quite tough early on because there was nowhere to eat at all, there were no decent shops to buy anything and also sadly, there was that terrible thing of young girls on drugs coming into the station trying to make some money through prostitution, and they would be asking me if I wanted business outside my own office.

SC: What are you reading?

JP: My neighbour, Robert Winder, has written a fascinating book on part of the history of England, which has just come out, The Last Wolf. I’ve recently also read Olivia Sudjic’s first novel which is quite extraordinary for somebody in their twenties.

SC: Favourite places to eat in London?

JP: Umu, the Japanese restaurant in Mayfair, is quite extraordinary. My home is my favourite place though but it’s a bit tough on Catherine to always have to cook.

SC: Favourite holiday destination?

JP: I’d rather anything than get on a plane but the Faroe Islands is the next one. They’ve got this lake, a kilometre long, which sits at the edge of this extraordinary cliff, so you’ve got the sea, the cliff and then the lake. In photographs, the sea looks like it’s being lifted up, as though it’s been Photoshopped.

Interview by Keshav Anand | Photography by Ana Cuba