Interview: In The Studio With Architects Casper Mueller Kneer

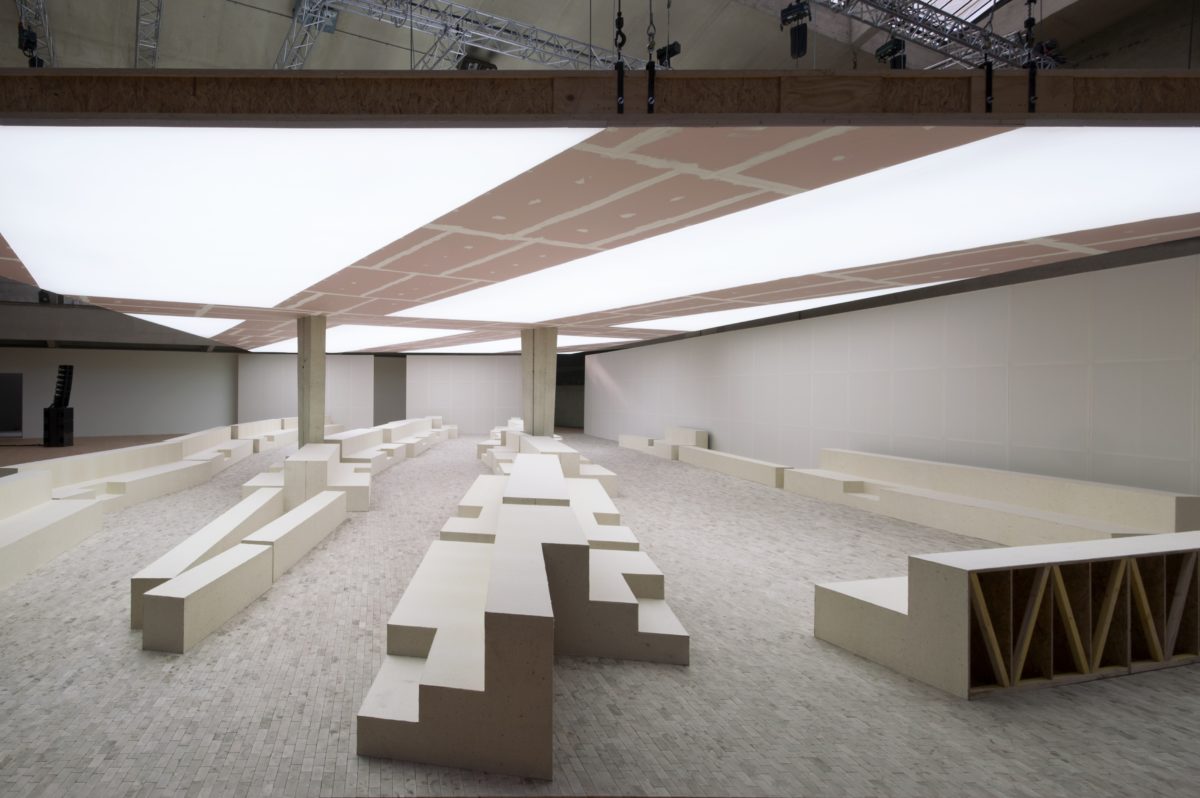

By Something CuratedCasper Mueller Kneer Architects was established in 2010 by Jens Casper, Marianne Mueller and Olaf Kneer, when the trio merged their London and Berlin practices. Since then the studio has developed a particular reputation for producing spaces for the arts, culture and fashion, with a distinctly materials-led focus. Recent projects include the critically acclaimed gallery for White Cube in Bermondsey, several collaborations with Paris based fashion house Céline worldwide, and exhibition designs for the Wellcome Trust, and the Jewish Museum in Berlin. Something Curated met with the architects at their Barbican studio to learn more.

Something Curated: Can you talk to us about your backgrounds – how did you get into this field?

Olaf Kneer: We’re all from Germany, but Marianne and me have lived in London for most of our lives, 28 years or so. We’ve always been back and forth between Germany and Great Britain, which is how we met Jens, in Berlin, 14 years ago.

Marianne Mueller: I met Olaf at the Architectural Association, which is still a really important reference point for us. It’s one of the most renowned schools of architecture in the world, with an independent programme.

OK: This was in the early 1990’s, which was a very interesting time. It was a strange time to stay in London, because it was super depressed here. There was a very long recession that had been going on for quite a while, and it felt like there weren’t many prospects for architects in this country. Maybe because of that, there were very interesting people in academia. It really felt like a lot of things were coming together at the AA. After having met in Berlin we introduced Jens to the AA, where Marianne and I were teaching. We ran a programme called “AA Berlin Laboratory”, which was an exchange programme, where we were all based in Berlin. We invited Jens to teach with us within that set-up, in September 2009. That strengthened our collaboration, and a bit later, we got an opportunity to work together in a more formal set-up, and founded the company.

MM: There’s this crossover between teaching and practice and real projects and academic projects, and I think that is something that combines us all. That’s what got us together.

SC: How would you describe the ethos of your practice?

MM: I would say that our practice is sort of research-focused. Research is partly practiced in academia and partly through live projects. That might be through a research position, or an academic position that is a platform in order to establish research or it might be through a fee paying project. There are two research strands. One is about material and the other is about, let’s say, heritage preservation, and found objects. The focus on materials, and material research allows us to develop a lot of materials that we work with, so we don’t only necessarily specify products, but we would also develop materials. There was a great array of projects in which we were able to do that. We also develop components, which is something that the practice is really interested in.

SC: Could you speak about any projects you’re currently working on?

Jens Casper: There are a number of projects that we are working on. In Berlin we are working on the transformation of an industrial site into an event space for three and a half thousand people, like a music hall, in Dortmund in West Germany. This project is called Phoenixhalle and will be finished within the next year.

MM: We continue to work in the art and exhibition context. That’s another strand that follows through with the practice. We work a lot with spaces for the arts. We’re currently working on another exhibition for the Barbican Centre, which is an ongoing collaborator. There are also a number of research projects which are currently going on, which relate back to the idea of heritage. We’re also currently working on projects with Curzon Cinemas and clients from the fashion world.

SC: What interested you in setting up an office in London?

OK: It’s not just London, it’s Berlin and London. London came about because of its connection to the academic world. Had we not had the AA connection, we wouldn’t have necessarily stayed here.

MM: The fascinating thing about London is that it’s such a hub. It somehow allowed us to work on projects globally. London really provides that sort of ground where you can work in many different places, and that’s something, especially in recent years, that has really taken off.

SC: Could you tell us about your collaborative dynamic?

JC: It’s not as if he’s the project manager and she’s the project designer or he handles the finances or whatever, it’s not like that. We’re three designing individuals with some very closely shared values.

SC: Is there any kind of system you’ve developed for approaching a new brief, or does it tend to be very organic?

MM: Perhaps it’s the other way around. The briefs come to us, because I think we present a certain attitude, and therefore, a lot of projects have come to us. In a sense, we don’t need a system because we simply work the way we do. No project starts from scratch. Every project has a history, that we somehow try to work with. Every building has a history; every place has a history. We look at these reference systems that we partly bring in from the outside, but the project may have its inherent reference system, which we’re trying to connect to.

JC: It’s interesting to have a project, like that one in China, where there is no context at all, to bring this method into the project: What can be referenced when there is very little to relate to? Every project needs a set of references to be developed.

SC: What was the narrative behind the White Cube Bermondsey gallery?

JC: There are a lot of narratives, but the most interesting may be that the building itself was an ordinary warehouse when we started. We were working with it as if it was a monument, and in the end we turned it into one.

OK: It was a very simple building. It was considered low quality, of no particular architectural value when we started looking at it. No one thought that it was beautiful, or that we should put a gallery in it. We didn’t dramatically transform it, but the few things that we did, changed it. It changed the way people looked at the building.

JC: We were looking for qualities that could be developed within the given setting. The structure was given, certain conventions were given, but the light for instance was something that we worked on. Every one of the spaces within the gallery has a different light condition. The proportions are important, and then you’ve got this long corridor, communicating like a street without any thresholds, that allows you to move in and out of gallery spaces without any constraints.

SC: What do you think are issues that architecture is or should be trying to solve in London at present?

OK: We thought about public space, and particularly the loss of public space. We’re wondering whether architects can contribute in a way to change the thinking. We need to encourage those people that make rules to think about the built environment and public space, and allow participation, and the kind of de-regimentation of public space.

MM: London is one of the cities where the privatisation of public space is most advanced in Europe. In that sense, it’s a really important issue.

SC: Why do you think art organisations and creative studios have been drawn to working with your practice?

MM: Perhaps because we’ve built up an expertise in working with these types of spaces. For display spaces, it is really important that architecture provides a sort of background. It is an architecture that would not enter into a competition with an object on display, but it would somehow provide a setting or framing or stage for this object. We think a lot about this relationship between the object and its setting, and between the viewer and the object. It is these relationships that we’ve been exploring in a number of projects.

SC: Preferred work attire?

OK: We’re quite relaxed. It’s funny, yesterday we had a new guy starting and he came with a tie. He’ll stop doing that very soon. Personally I love wearing Yang Li, he an amazing designer. There’s a kind of simplicity and seriousness about his work.

MM: I really enjoy wearing clothes designed by women. It’s still very rare to see female designers. They deserve more attention.

SC: What are your favourite places to eat in London?

MM: This has been our favourite place for a really long time, and it’s St. John. We really like the attitude that is taken towards the food, and we love the chef. He went to the AA, and he got his honorary diploma this summer, so it was a great moment.

Interview by Keshav Anand | Photography by Dexter Lander