Interview: Curator Valentina Ravaglia On Tate Modern’s Major New Nam June Paik Show

By Something CuratedFrom 17 October 2019 – 9 February 2020, Tate Modern will present a major exhibition of the work of visionary Korean artist Nam June Paik. Renowned for his pioneering use of emerging technologies, Paik’s innovative yet playfully entertaining work remains an inspiration for artists, musicians and performers across the globe. Organised by Tate Modern and San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, this will be the most comprehensive survey of the artist’s work ever staged in the UK, bringing together over 200 pieces in a mesmerising riot of light and sound.

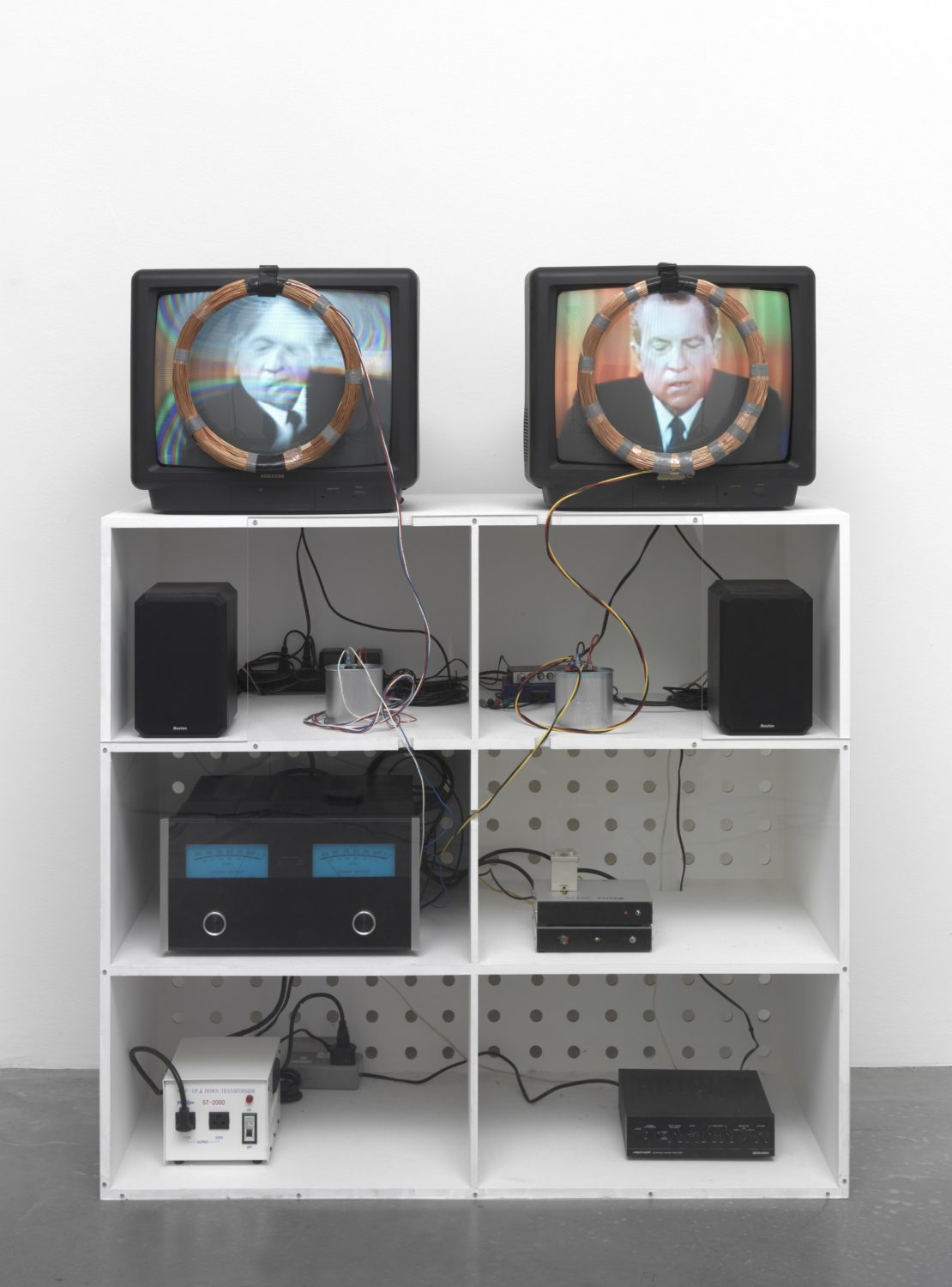

Paik developed a collaborative and interdisciplinary practice that foresaw the importance of mass media and new technologies, coining the phrase ‘electronic superhighway’ to predict the future of communication in an internet age. He has become synonymous with the electronic image through a prodigious output of manipulated TV sets, live performances, global television broadcasts, single-channel videos, and video installations. Ahead of the show’s launch, Something Curated spoke with one of the exhibition’s curators, Valentina Ravaglia, to learn more.

Something Curated: What are you aiming to achieve with the upcoming Nam June Paik exhibition?

Valentina Ravaglia: Paik is a prime example of an artist transcending boundaries, through his anarchic mixing of media as well as of cultural references. He was a truly transnational artist working over three continents and he never missed a chance to expand his horizons; he often worked collaboratively and across disciplines – from music and performance to science and mass entertainment. We wanted to put together an exhibition that can convey the multifaceted nature of his career beyond his reputation as a pioneer of video: his oeuvre has so much more to say.

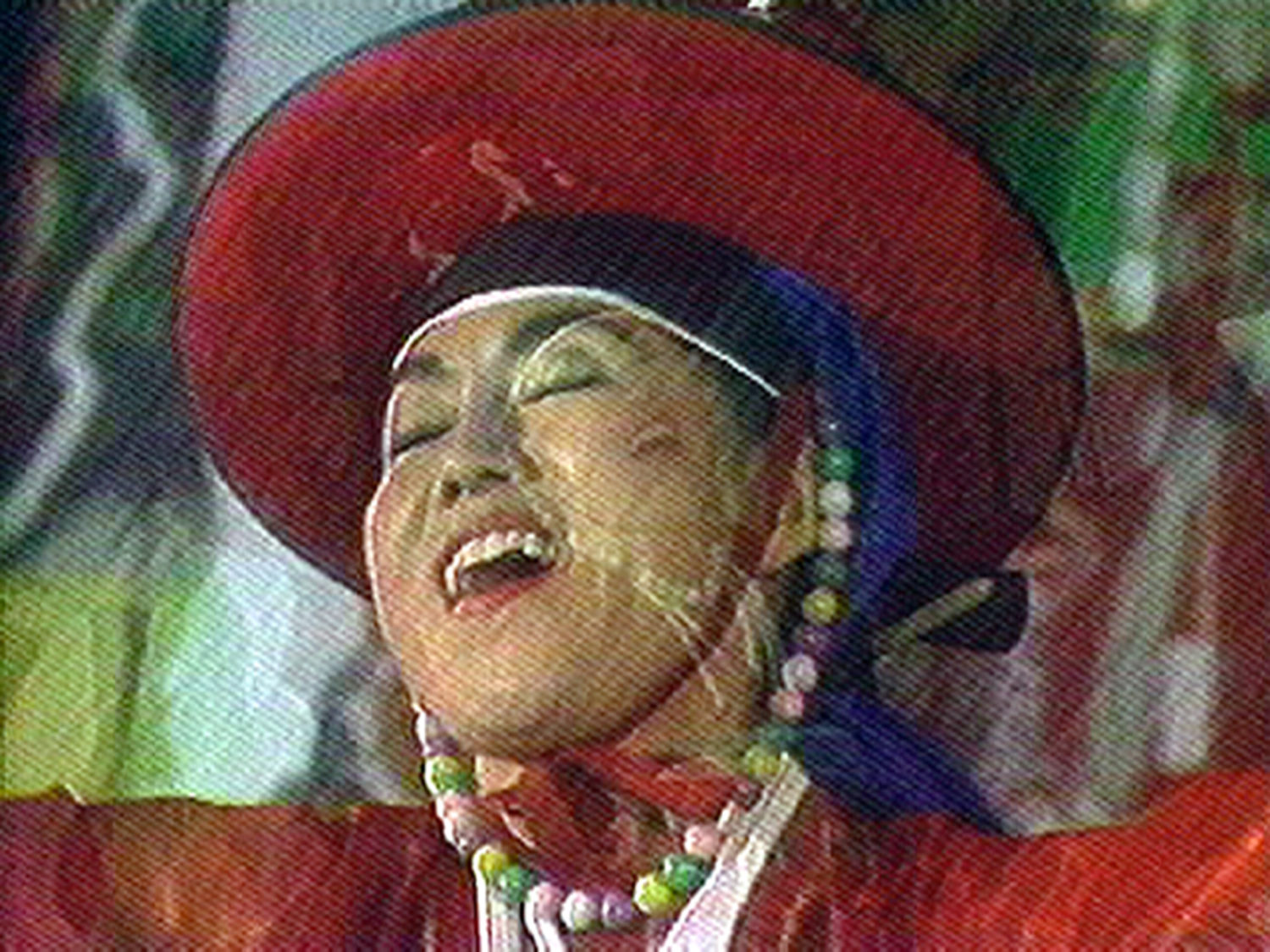

Hopefully visitors will leave the exhibition with their expectations having been subverted, one way or another. Those who are acquainted with Paik’s most iconic works will discover new aspects of his oeuvre and biography they were not familiar with, while those who don’t know Paik at all will have been introduced to an artist whose output is extremely diverse in terms of medium, tone, scale, subject matter and cultural origins: from a blank, silent 16mm projection titled Zen for Film (1962-64) to his Sistine Chapel of 1993, a room-sized, four-channel installation with multiple projectors creating an immersive riot of colour and noise, featuring John Cage, David Bowie, Korean dancers and swimming fish.

SC: Why is Paik an important artist for us to consider now?

VR: Paik has not had a large monographic exhibition in London since his solo show at the Hayward Gallery in 1988 (Nam June Paik. Video Works 1963-88). Considering how influential Paik has proven to be on generations of artists working with video and mass media technologies, as well as the potential his art has to connect to a younger audience of digital natives, this felt like a blind spot that needed to be corrected at once. The fact that this exhibition will travel to five venues overall (Tate Modern, the Stedelijk, the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, SFMOMA and the National Gallery of Singapore) is surely a testimony to its timeliness.

Our exhibition however also strives to demonstrate that Paik was far from being a pure technophile tinkering with electronics and dabbling in video effects. He truly understood the potential as well as the dangers of mass media and was interested in the way technology affected society throughout history. He had an incredibly sharp critical and philosophical insight into the subject, one that resonates profoundly with today’s concerns with environmental sustainability, automation, surveillance and information control. Paik didn’t just predict the Internet when he wrote about the ‘electronic super-highway’ in 1974: he thought of its creative, economic and sociological ramifications, too.

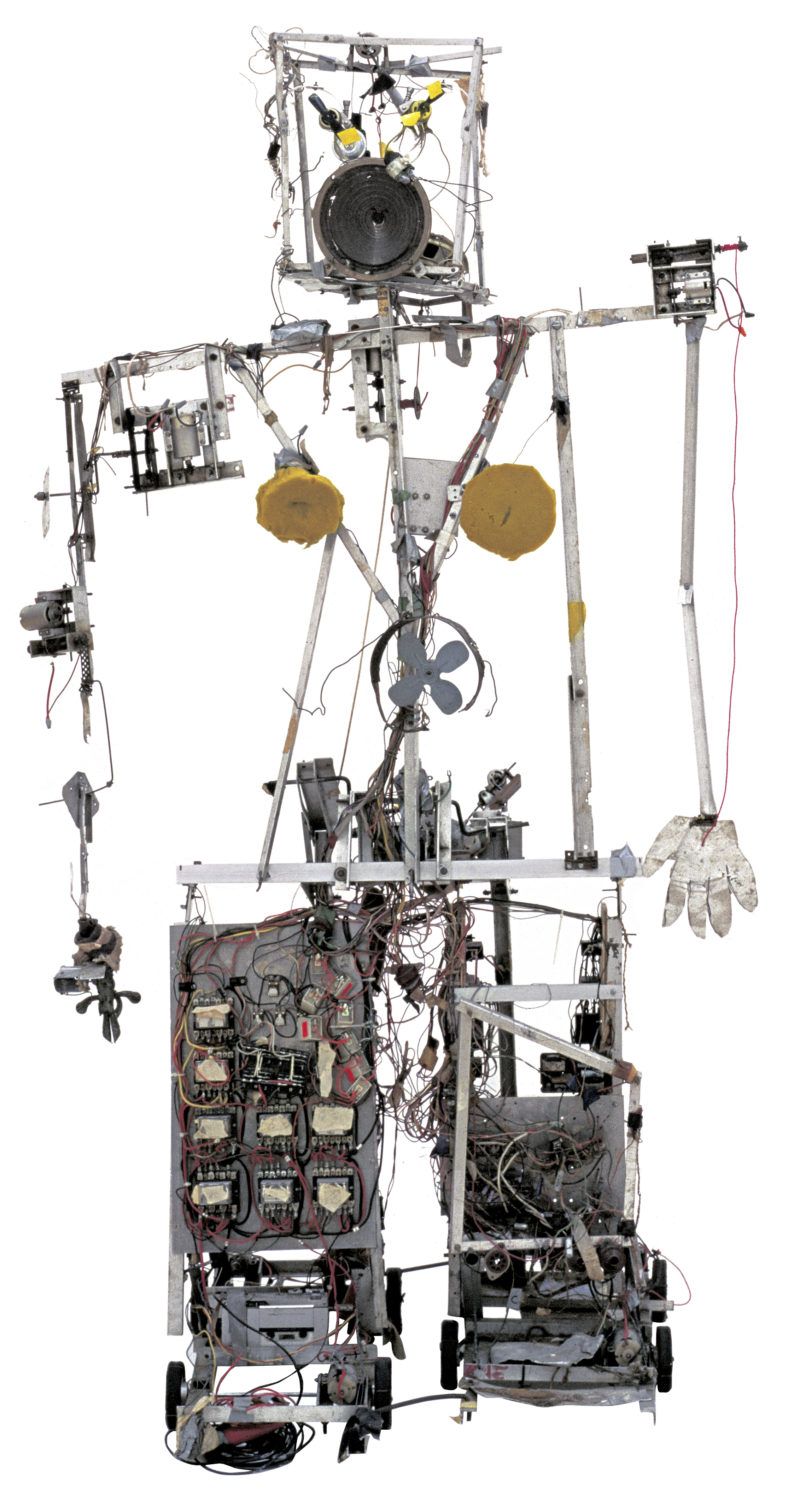

Paik wanted to show a way forward through his work, a future where art and technology can work together as equals, not just illustrating or imitating one another. For Paik artists were the true innovators because of their license to mess with technology and to keep it connected to its human side. That’s why his robots look so awkward and his performances – like those with cellist Charlotte Moorman wearing his ‘TV props’ – so absurd and playful. This is also why he pointed the camera at the viewer as often as he pointed it back at technology itself. His interactive artworks, like Random Access (1963) and Three Camera Participation/Participation TV (1969/2001), invite the viewer to take control of technology – partly so that it would not take control of them.

SC: I understand the show is set to bring together over 200 works, from early compositions and performance to video and large-scale television installations – could you tell us about your approach to displaying these diverse elements?

VR: The exhibition doesn’t follow a chronological order, and is essentially constructed around a number of turning points: the ‘Exposition of Music-Electronic Television’ exhibition, his moments of radical experimentation with technology including his collaboration with engineer Shuya Abe in developing the Paik-Abe Video Synthesizer, his live broadcast and satellite projects, participation in the Venice Biennale representing Germany in 1993, and of course his encounters with his many key collaborators including John Cage, Joseph Beuys, Charlotte Moorman and Merce Cunningham.

SC: Can you expand on Paik’s pivotal role in Fluxus?

VR: Paik met Fluxus founder George Maciunas in Germany, just as the former was beginning to create works that pushed established disciplinary boundaries, particularly those between music and visual art. Paik’s early works were also concerned with everyday gestures and objects, incorporating them as elements of his happenings as an ‘action musician’. These aspects resonated with Maciunas’ ideas around the nascent Fluxus movement, and this early encounter led to Paik co-organising and taking part in some of Fluxus’ founding events in Wuppertal, Düsseldorf and Wiesbaden. Paik’s ideas and works were a huge part of early Fluxus: he collaborated with a variety of international Fluxus artists and often took part in their works as a performer as well.

Furthermore, it was Paik who introduced Joseph Beuys to Maciunas and Fluxus, and he served as an international ambassador for Fluxus as he travelled between Europe, Japan and the US. Even though Maciunas and Paik had some disagreements over the years, particularly over Paik’s participation in events organised by Charlotte Moorman who Maciunas despised, Paik continued to make Fluxus-influenced works for decades. He also remained a friend and admirer of the founder of Fluxus, as demonstrated by Piano Duet – In Memoriam George Maciunas (1978), a Paik and Beuys’ collaborative performance commemorating the founder of Fluxus after his untimely passing.

Nam June Paik | 17 October 2019 – 9 February 2020 at Tate Modern, London

Interview by Keshav Anand

Feature image: The Mongolian Tent, 1993. Courtesy LWL-Museum für Kunst und Kultur Westfälisches Landesmuseum. Photo Hanna Neander.