Interview: SO–IL’s Florian Idenburg & Jing Liu On Architecture For Future Culture

By Something CuratedHelmed by co-founders Jing Liu and Florian Idenburg, New York-based architecture practice SO–IL’s diverse and globe-spanning portfolio comprises everything from art galleries and fashion showrooms to social housing and interactive public installations. With a client list including the likes of the Whitney Museum, Telfar, Google, Frieze, Versace, the Guggenheim, and K11 Art Foundation, since 2008, the practice has carved itself a distinct and covetable position in the industry. Their ambitious undertaking for K11, Hong Kong opened its doors last year, and this summer marks the launch of Brooklyn’s Amant Art Campus, a cultural incubator designed by SO–IL to integrate artist studios, gallery spaces, offices and a café. To learn more about SO–IL’s fascinating work, Liu and Idenburg’s collaborative relationship, and what’s next for the practice in light of the pandemic, Something Curated spoke with the architects.

Something Curated: Can you give us some insight into your respective backgrounds and how you entered the field of architecture?

Florian Idenburg: Jing was born in Nanjing, China, attended high school in Japan and got her architectural education in New Orleans at Tulane. I grew up in the Netherlands and Colombia. After graduating from the TUDelft, I worked for SANAA in Tokyo for eight years. This is where we met. After completing the New Museum in New York for SANAA, we started SO–IL, in Brooklyn, New York, in 2008.

Jing Liu: While we are based in New York, we really consider ourselves a global firm. We continue to learn from diverse cultures, and test our ideas in the broad context of their validity and agency. We believe that architecture is a material practice as well as a cultural one – both are very specific to their place. So it is important to do buildings in different places so we do not get contrived in our own comfort.

SC: How would you describe the ethos of SO–IL?

FI: We create spaces and objects for future culture. What we mean by that is that we believe that new cultures can emerge through collision and collaboration between people with different perspectives and experiences. Diverse in origin, our team of collaborators speaks a dozen languages and is informed by global narratives and perspectives. We are both locally-rooted and nationless. In a digitised world that increasingly draws one inward, our architecture is outward-looking, engendering meaningful dialogue with what is materially and psychologically outside of ourselves. We explore how the creation of environments and objects inspires lasting positive intellectual and societal engagement.

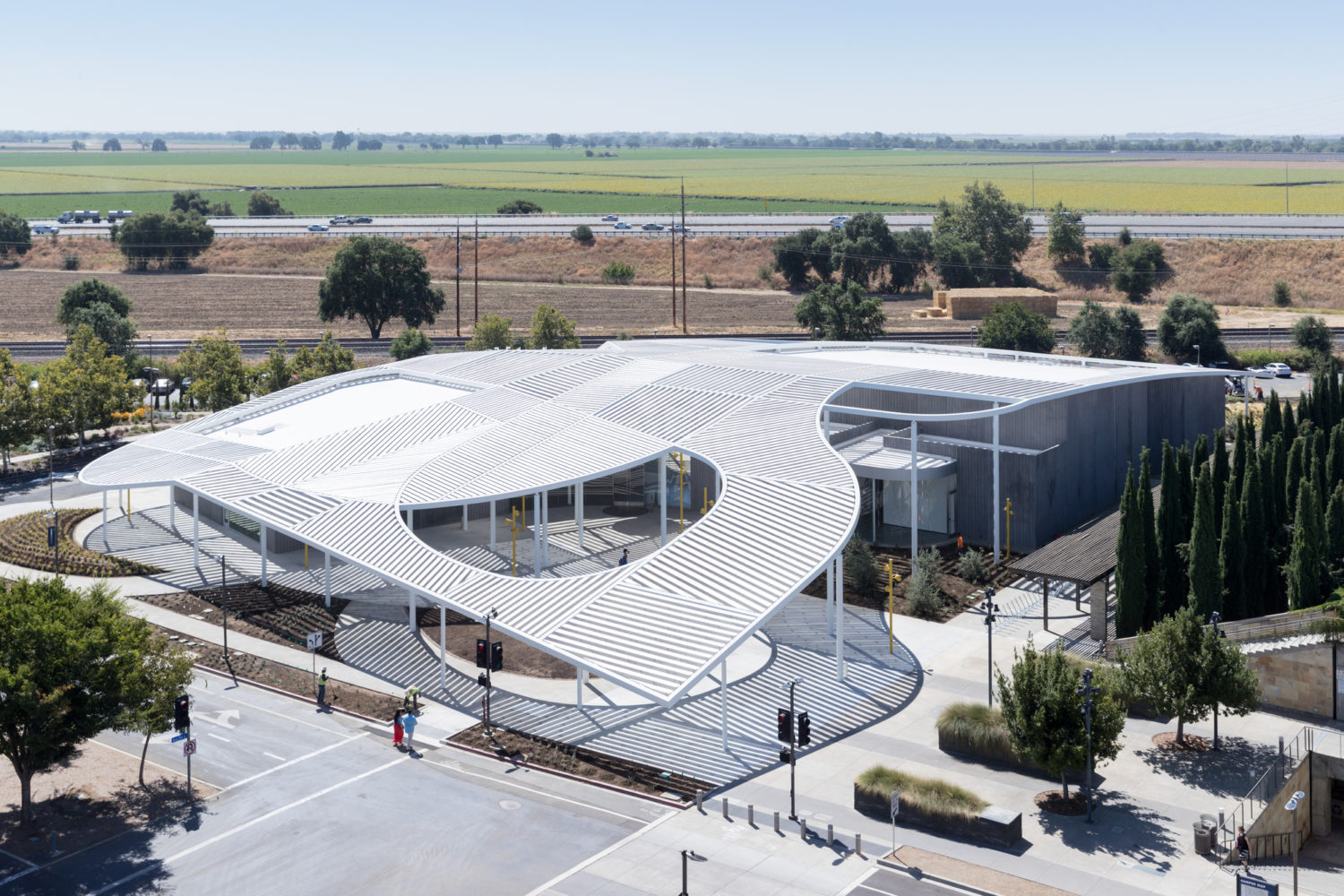

SC: What interests you in designing arts and cultural venues, for example, The Jan Shrem and Maria Manetti Shrem Museum of Art?

FI: At their best, arts venues and cultural institutions are platforms for ideas and discourse. We recognise that the arts can be co-opted to benefit financial or political agendas, but arts venues ideally offer frameworks for intellectual concepts and contemplations. They offer people time away from the every day, and hopefully, a space that stimulates the senses and inspires thoughts. There is a certain freedom in designing these spaces because they are built mostly to offer rather than extract something.

JL: Spaces for the arts also demand less “decoration,” since art is at the centre of it. So it is possible to focus on the spatial and tectonic. As they are also often the spaces where one is able to slow down, decompress and contemplate, where one discovers something new, there is the opportunity for people to notice these subtleties in architecture.

SC: Could you expand on your collaborative dynamic?

FI: Jing and I are in a continuous dialogue, growing through insights we encounter on our path. The learning from others we see as one of the most joyous things of practicing today. We are fortunate enough to be involved in projects in such a wide variety of settings that every project offers something new. The lessons we learn we bring to the next project, and as such, we have been able to have a very expansive view. A single mind can realise no project.

JL: This kind of collaboration does not stop with the two of us. Our studio works very collaboratively, and with engineers, designers from other disciplines and builders and makers as well. We evolve together within a broad context.

SC: What inspired the spectacular chainmail veil utilised at Kukje Gallery, Seoul?

FI: I have had a long interest in ambiguous forms and the notion of veiling. The idea that a form cannot be read as a simple outline or diagram but offers mystery and intrigue was something we found compelling. A standard white cube gallery would be too austere for the historic urban fabric where the gallery is located. We pushed all circulation to the periphery and enveloped the whole structure in a hand-fabricated chainmail veil, unique in strength and drape. The façade’s draped form echoes the surrounding rooflines. The mesh’s play of reflectivity and shadow gives the building mass a light appearance.

JL: We are always drawn to objects and bodies that are able to offer complexity and variety and yet are not complicated. What gives form to Kukje is rather simple; functional programmes and tension forces, the result is a surprisingly complex form that maintains the simplicity of the logic it is derived from.

SC: What are you working on at present, and how has the pandemic affected your way of operating?

FI: The year 2021 marks an important year in our practice. We are opening five projects on three continents, spanning from the UCCA Museum in Shanghai to Las Americas, a social housing project in Leon, Mexico. We are also finishing our first buildings in New York City, which is exciting, including Amant, an artist residency program in Brooklyn, as well as the studio for the artist Ghada Amer in Manhattan. The lockdowns made our office even more hybrid, but we were already pretty comfortable to work from various locations using multiple tools. We did use the quiet year to work on our archive.

We are currently working on the design and construction of three residential projects in our neighbourhood. The pandemic affected their conception. We focused on making the public circulation from street to home light-filled and full of fresh air. Additionally, we designed the plans with future pandemics in mind. One of the most lasting impacts of last year is that it has accelerated our transition to becoming much more mindful of the effects of our actions, both socially and environmentally.

SC: What do you want to learn more about?

FI: We want to develop our knowledge about the implications of design. How can we shape our buildings to minimise their negative impact on the environment while maximising what it gives back to the communities we find ourselves in. We are part of an organisation, Design for Freedom, which aims at ridding the construction industry of modern-day slavery. Unfortunately, there is a lot of ignorance amongst designers, including ourselves, regarding material selection. We often choose material in an attempt to balance the budget with aesthetics. It is currently hard to know how these materials were produced, especially the raw material, like aggregates, cement, metals, etc. For instance, it is easy to buy slavery-free chocolate, but try to do the same for ceramic tiles.

JL: We are also very much interested in the practice of architecture that does not take form in new construction. Adaptive reuse, renovation, repurposing are often much less energy and resource demanding than any form of recycling. So to think critically about how to reuse existing structures will be an important topic in the field of architecture.

Feature image: Kukje Gallery—K3, Seoul, South Korea. Courtesy SO–IL