Interview: Spatial Design Studio Limbo Accra Breathes New Life Into Ghana’s Urban Wastelands

By Something CuratedEstablished in Ghana by co-founders Dominique Petit-Frère and Emil Grip, spatial design studio Limbo Accra traverses the intersections between art, architecture and sustainability, reacting to the swift modernisation of West Africa’s expanding urban centres. Limbo’s diverse design-led projects are interdisciplinary and experimental, spanning immersive public installations made from repurposed urban detritus, moving image and photography, all underpinned by the aesthetic and cultural significance of unfinished and decayed concrete structures. Fostering new and important conversations around the realities and consequences of rapid urban development, the architecturally minded platform seeks to shine a light on the exploitation of the construction industry, while repurposing and reactivating sites that may have otherwise existed in an indefinite state of disuse. To learn more about the fascinating collective and their exciting work, Something Curated spoke with Limbo Accra’s founders.

Something Curated: Can you give us some insight into your respective backgrounds and how your working relationship came about?

Limbo Accra: Our backgrounds are within urban development and education – so our approach to design and architecture has always been from an intuitive and autodidact perspective. The whole process for us has always been formed by the multicultural essence in our relation to each other, since we are constantly moving between Accra, Copenhagen and New York.

SC: How was Limbo Accra born; and what is the significance of the platform’s name?

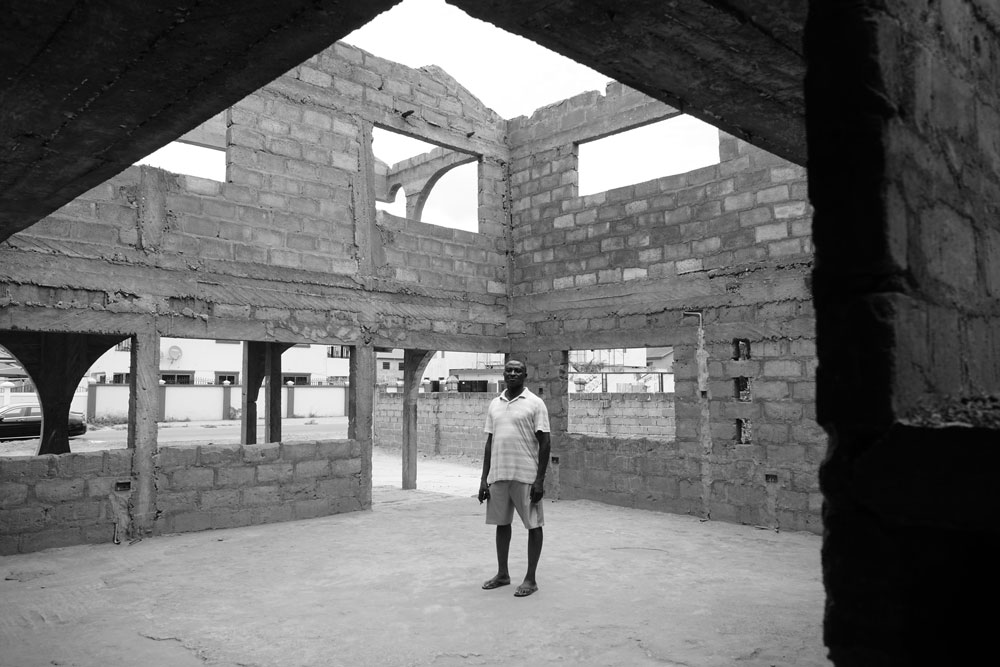

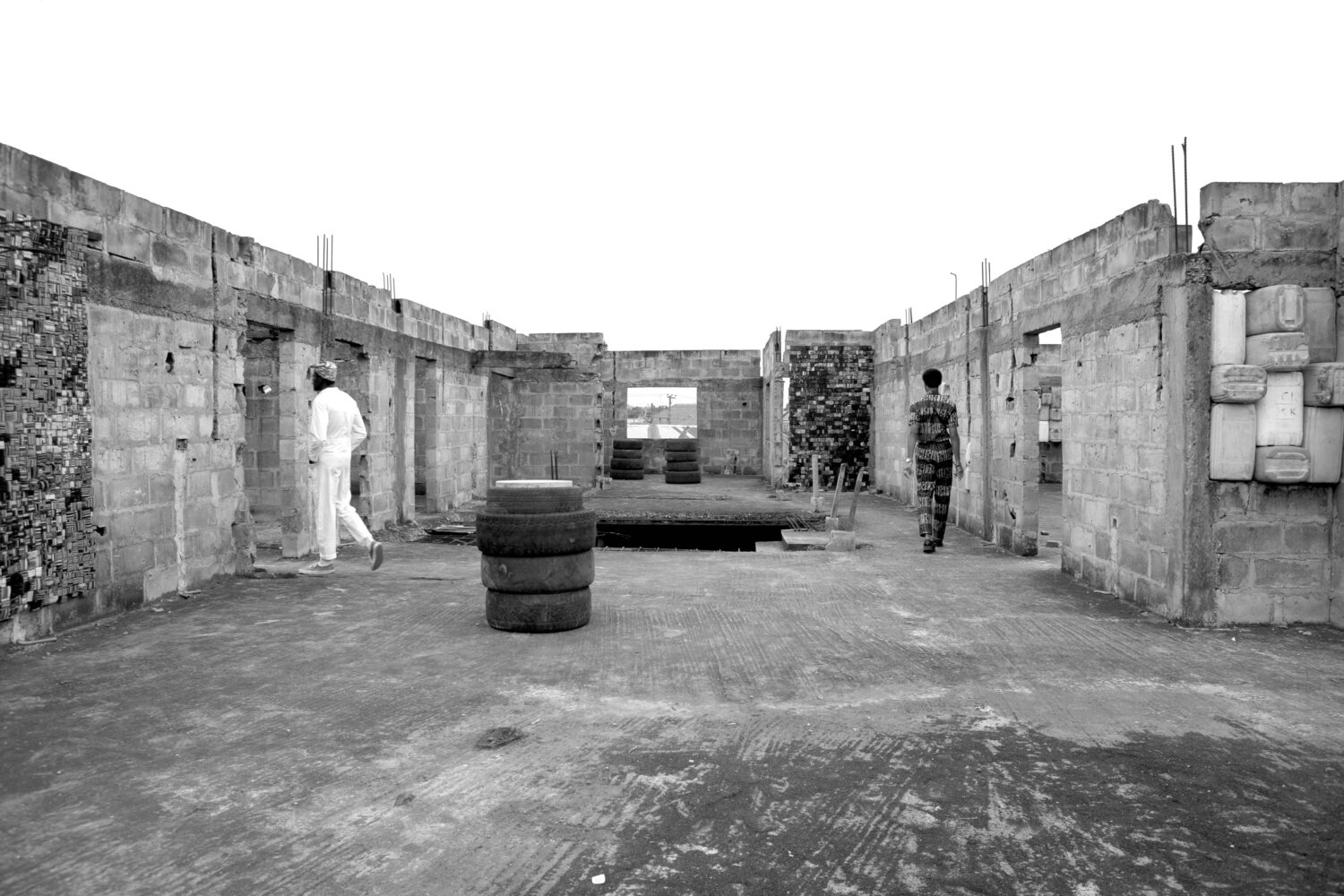

LA: Limbo Accra was born out of a curiosity to transform and investigate the architectural and built conditions of modernising West African cities as we were keen on exploring the intersection between art, architecture and sustainability within this new-age context. The studio’s name is a nod to the many incomplete and since-abandoned buildings in Accra and other West African cities, their sites in a state of limbo. When we started Limbo in 2018, it was truly a transformative period in Accra and I think we both felt compelled to take action in that transformation. For us it was very evident that this large scale of uncompleted property developments littered around the city of Accra held a vast amount of opportunities for activations and conversation among the growing creative community and city at large.

SC: What are you currently working on?

LA: Currently we are developing a digital archive expanding our documentation of voided sites in Limbo around the African continent, together with artist Ibiye Camp. The project functions under the working title: ‘Into the Void: Sites of Digital Renewal’ and is a collaborative digital experience and archive of scanned voided buildings which will allow individuals to have first-person-controller movement to interact with scanned concrete sites. Visitors will be able to select their own views from the exterior and interior. We just wrapped up our quest for establishing a design competition in Accra and Lagos together with NMbello Studio. Although the first competition is completed, we are just starting our journey towards expanding our research and uplifting young talent in the West African region.

Within our architectural studio we have a few projects that are planned to enter the construction phase within the next year. Together with Leroy Wadie we are designing and consulting on the new Wadie Design Academy which is set to be a design incubator in Ghana. We are also designing the first Fulani Kitchen Foundation for our dear friend and renowned chef, Chef Binta in Northern Ghana along with a few private residences, one of which will start construction later this year. Finally we are continuing our spatial activation series ‘Architecture is A Party’ together with Black Discourse and Manju Journal, using architectural heritage sites in Africa to spark dialogue on design, space and architecture in our contemporary society. If all goes well, you will be able to catch us at the 2022 Dakar Biennale for our second iteration.

SC: Could you expand on the thinking behind Limo Site Location — what interests you in occupying uncompleted developments?

LA: So the Limbo sites are interesting for us in an African context because it poses the opportunity to bridge two societal issues within the urban landscape: extensive voided structures and lack of public space. Essentially we are experimenting with the idea of using these sites as soft activations for people to question the neighbourhoods and cities; asking “how are we being intentional in the way we design and create spaces for people?” I think that it’s interesting that we as a species have done so much research on what a good habitat consists of for lets say a gorilla or a polar bear, but undermined the integrity for what a good habitat is for homo sapiens. That’s an interesting thought and one that we are keen to further explore. The work of Jan Gehl together with our Burkina neighbour Francis Kere, which bridges architecture and psychology seems not only fascinating but simply logical for us when we look and talk about developing cities.

SC: Can you tell us more about the collective’s collaborative dynamic and the other creatives involved?

LA: Essentially Limbo is an ever-morphing studio, working with creatives and real people from all over the world. Within our practice we are strong believers in the collective effort to change – we are simply better when we are more people to solve the problems. It’s not so much a quality vs. quantity, but more an approach to problem solving. Through our work with Limbo we have experienced first hand the incredible power of passionate people. It’s like, if you put the right group of individuals together on a mission that’s empowering for them, truly unexpected outcomes will appear. We are still getting surprised about the power and willingness to foster change that exists within the creative community, and with media platforms like Instagram we can all connect and join forces. It feels like a super transformative time period we are going through.

SC: How would you describe the ethos of Limbo Accra; and what do you hope to achieve with it?

LA: Our practice exists in this fluid space between juxtapositions, because we never allow ourselves to be stagnant – Limbo is constantly evolving, morphing and growing. Essentially we are simply here to question and investigate the reality of the world we see and how we can be more intentional about our role within in it as spatial practitioners.

Feature image — Photo: Sierra Nallo. Courtesy Limbo Accra