Fashion & The Paradox Of Exposure

By Something CuratedThe science of managing a brand’s exposure is a complex task and one which requires perpetual review and revision. While in the majority of cases, certainly when reflecting on emerging fashion labels, gaining an audience is a herculean task, sustaining that audience is often even tougher. On the other end of the spectrum, rapid growth without focus can lead to overexposure, which is inevitably harmful. With many contributing factors relating to exposure affecting a brand’s commercial success, including advertising, endorsements, collaborations, distribution strategies and social media, it is interesting to consider this phenomenon in relation to the fashion industry.

Theories of exposure

‘Selective exposure’ is a theory within the practice of psychology, often used in media and communication research, historically referring to individuals’ tendencies to favour information, reinforcing their pre-existing views while avoiding contradictory information. People tend to select specific aspects of exposed information which they incorporate into their mind-set. These selections are made based on their existing perspectives, beliefs, attitudes and decisions. Essentially, we can mentally dissect the information we are exposed to and select favourable evidence, while ignoring the unfavourable. The foundation of this theory is rooted in the idea of cognitive dissonance, which asserts that when individuals are confronted with contrasting ideas, mental defence mechanisms are activated to produce harmony between new ideas and pre-existing principles, maintaining equilibrium.

The ‘mere-exposure effect’ is a mode by which people tend to develop a preference for things merely because they are familiar with them. In social psychology, this effect is sometimes called the familiarity principle. The effect has been demonstrated with many kinds of things, including words, paintings, pictures of faces, geometric figures, and sounds. In studies of interpersonal attraction, the more often a person is seen by someone, the more pleasing and likeable that person appears to be. In the 1960s, a series of experiments by Robert Zajonc demonstrated that simply exposing subjects to a familiar stimulus led them to rate it more positively than other, similar stimuli which had not been presented. According to Zajonc, the mere-exposure effect is capable of taking place without conscious cognition, and that “preferences need no inferences”. The most obvious application of the mere-exposure effect is found in advertising, but research has been mixed as to its effectiveness at enhancing consumer attitudes.

Another study, carried out by Charles Fombrun and Mark Shanley in 1990, showed that higher levels of media exposure are associated with lower reputations for companies, even when the mere exposure is mostly positive. A subsequent review of the research by Scott Highhouse & Margaret E. Brooks concluded that exposure leads to ambivalence because it brings about a large number of associations, which tend to be both favourable and unfavourable. Indisputably, exposure is most helpful when a brand or product is new and unfamiliar to consumers. In advertising, ‘effective frequency’ is the number of times a person must be exposed to an advertising message before a response is made and before exposure is considered wasteful, but it remains unclear whether an optimal level of exposure to an advertisement exists.

Demand and desire

In just three years, Vetements founded by brothers Guram and Demna Gvasalia has emerged as one of the most disruptive in the industry, rejecting the traditional show schedule, combining its men’s and women’s collections, harnessing the power of social media, and building a business model based on the sale of limited numbers of expensive clothes. In an interview with The Financial Times in early 2017, Gvasalia explained: “Luxury is like dating. If something is available and in front of you, it’s less desirable. Scarcity is what defines it. One of the ways to create scarcity is to reduce the supply curve. The more demand there is, the more desire it creates. Desire is the key value in luxury business.”

Protective of his eponymous brand’s coverage, French footwear designer Christian Louboutin flourished for many years without paid advertising, focussing rather on developing exclusive products which appealed to celebrities. In an interview with Forbes in 2016, he said: “The best advertising is the pleasure of women. You don’t need to advertise when there are many women who appreciate what you are doing. I don’t work according to a strategy – I follow what I feel is right at that moment.” This approach has certainly worked, as today the designer’s name “almost became like Frigidaire,” he says. That is to say, a brand name turned byword. Louboutin and his trademark red soles have been a persistent presence in pop culture for years, featuring in television, film, music and novels.

In the know

Capitalising on the allure of the limited, streetwear brands have co-opted the “drop” system, whereby a reduced run of merchandise is announced and sold exclusively at certain locations for a short period. The hype leading up to such events, bolstered by social media, recurrently ensures products sell-out, keeping the demand for a brand high. Megabrands like Nike have honed in on comparable methods, collaborating with designers and artists to create special edition products for those in the know. Bringing to the ubiquitous brand a new degree of cultural capital, most recently, designer Virgil Abloh teamed up with Nike to release a limited collection of ten re-imagined footwear classics from the brand’s extensive archive. The one-off prototypes were given to Abloh’s staff to wear at the following Design Miami, where he presented furniture for his brand Off-White. This month, select retailers, including London’s Dover Street Market, used a raffle system to allocate shoes to ardent customers.

Following the abundant and ultimately tarnishing presence of Burberry’s Haymarket check in the 2000’s, under the direction of Christopher Bailey, the British heritage label slowly managed to reclaim its standing as a desirable luxury brand over the course of several years. Interestingly, following numerous seasons of subtler iterations of the check, in 2017, Burberry collaborated with Russian streetwear designer Gosha Rubchinskiy, producing a collection which seemingly paid homage to the period leading to the British brand’s demise. Here again, a notion of being in the know comes into play, with a humorous sense of irony embedded in the garments.

A digital age

Burberry was one of the earliest to actively embrace social media, developing a new type of control over its exposure, posting behind-the-scenes pictures and videos on its Instagram and Snapchat channels when the platforms first emerged. It was also the first of the big fashion houses to “live stream” its shows online, and, on certain platforms, customers were able to click through to buy garments as soon as they saw them on the runway. While the company is vague about the exact breakdown of online versus brick-and-mortar shop sales, it stated in 2016 that the “majority of traffic” to its website now comes from mobile, its “fastest growing digital channel.”

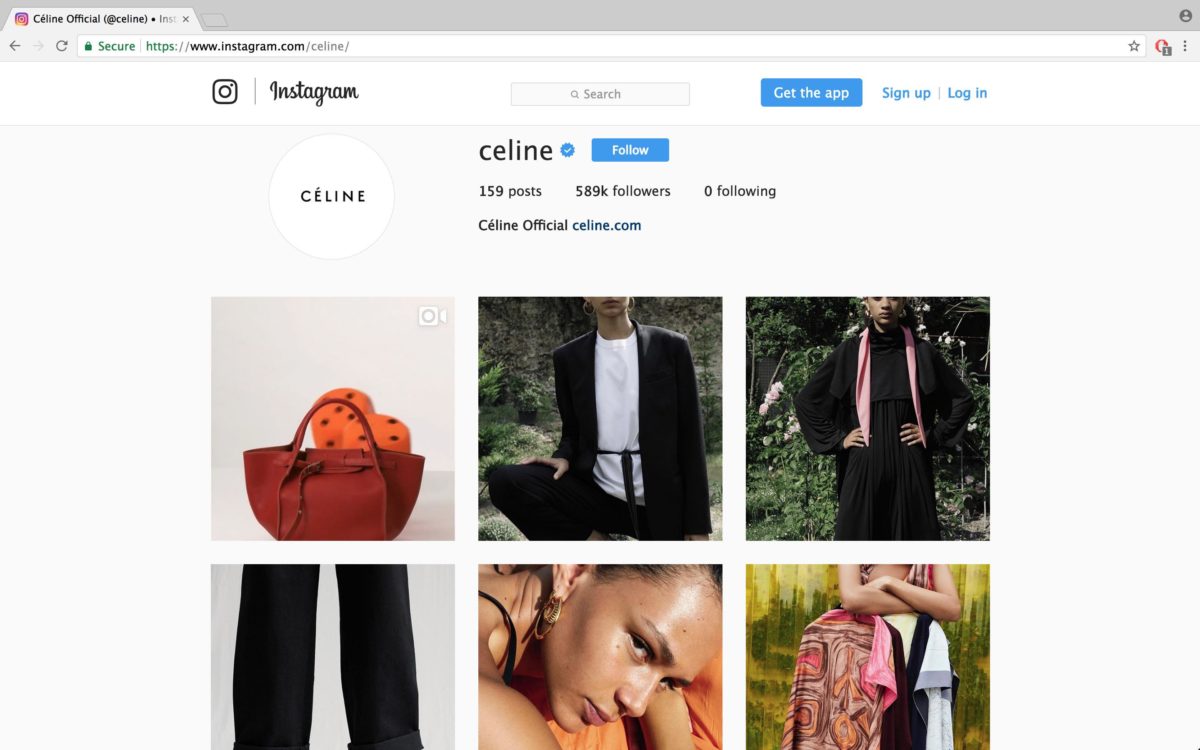

Word spread that French fashion house Céline was reportedly planning to launch an e-commerce site in 2017, and just two days before it’s A/W17 show in Paris, the luxury brand finally joined Instagram. Céline was one of the last fashion holdouts in the digital age. Its change of heart can likely be attributed in part to its recently appointed CEO, Séverine Merle. While discerning whether sales are directly linked to social media campaigns is difficult, companies with higher levels of engagement on Instagram have been reported to be growing their online sales faster than their less erudite rivals, upturning the traditional fashion hierarchy. Domenic Venneri, founder of California-based digital marketing agency Vokent, told the BBC in 2016 that in some cases, not just the models but the entire backstage team, including the make-up artists, stylists and producers, are selected according to their influence on social media, when creating a campaign.

.

The dangers of overexposure

Mismanagement of a successful brand, resulting in overexposure, can cause it to go into decline, diluting hard-earned brand equity. After all, luxury brands are viewed as such because they fiercely manage their brand exposure, paying close attention to both its frequency and reach. While they are careful to ensure that their brands are visible to the right constituencies, there is always an awareness of the dangers of overexposure. Limiting access maintains a label’s pedigree, preserving an element of scarcity or intrigue, which keeps it covetable. A victim of its own success, once a brand is overexposed it becomes adulterated and eventually weakens; while overexposure can go undetected in the short-term, this principle tends to hold true over time.

While Michael Kors continues to open hundreds of stores around the world, the brand recently reported earnings for the fourth quarter of fiscal 2017, with sales down by 7.6%. In 2016, Business Insider’s Mallory Schlossberg stated: “It’s a classic tale: when a brand is overexposed it loses its level of luxury. After all, when everyone has the same bag, it no longer becomes covetable. Coach for awhile suffered from this problem, but it has been working for awhile to its luxury image.” In the case of Kors, as with other brands facing similar trajectories, it is challenging to get consumers to pay a premium when they know they can get something on sale or from an outlet. Ultimately, a distribution strategy is as crucial to a brand’s exposure as advertising and social media.

Feature image: Louis Vuitton Monogram Denim Shawl (via Louis Vuitton)