London Fashion’s Obsession With Graduates

By Something CuratedAs a discipline, architecture has a well-known reputation for being a slow burner, a trade which requires a gradual building of trust over many decades, likely for good reason. There has been a stereotype of the architect as a grey-haired white male which has only in recent years been somewhat disrupted by a younger and more diverse cast of characters. Interior architecture, spaces such as pavilions, and exhibition design, offer younger practitioners channels to access building projects. Rem Koolhaas, the Pritzker Prize-winning Dutch architect and theorist, spoke with Mohsen Mostafavi, dean of the Harvard Graduate School of Design, in the closing keynote for the 2016 AIA convention, in which Koolhaas pointed out: “Architecture is a profession that takes an enormous amount of time. The least architectural effort takes at least four or five or six years, and that speed is really too slow for the revolutions that are taking place.”

The logistical practicalities and temporal implications of designing a building, or for that matter, a city, mean that a certain level of credibility must be established, starting with the completion of a lengthy education, which of course all takes a long time. On the other end of the spectrum, creative disciplines like fine art and fashion, seem to more openly embrace a sense of youthful irreverence, at least on the surface. Reflecting on Koolhaas’s point, perhaps the relative immediacy of these outputs allow them to feel in keeping with social and political movements, or as he put it, “revolutions.” Though the notion of capturing and marketing youth has always been prominent, the decided focus on super young professionals in diverse creative fields, certainly in a London context, is somewhat of a recent phenomenon.

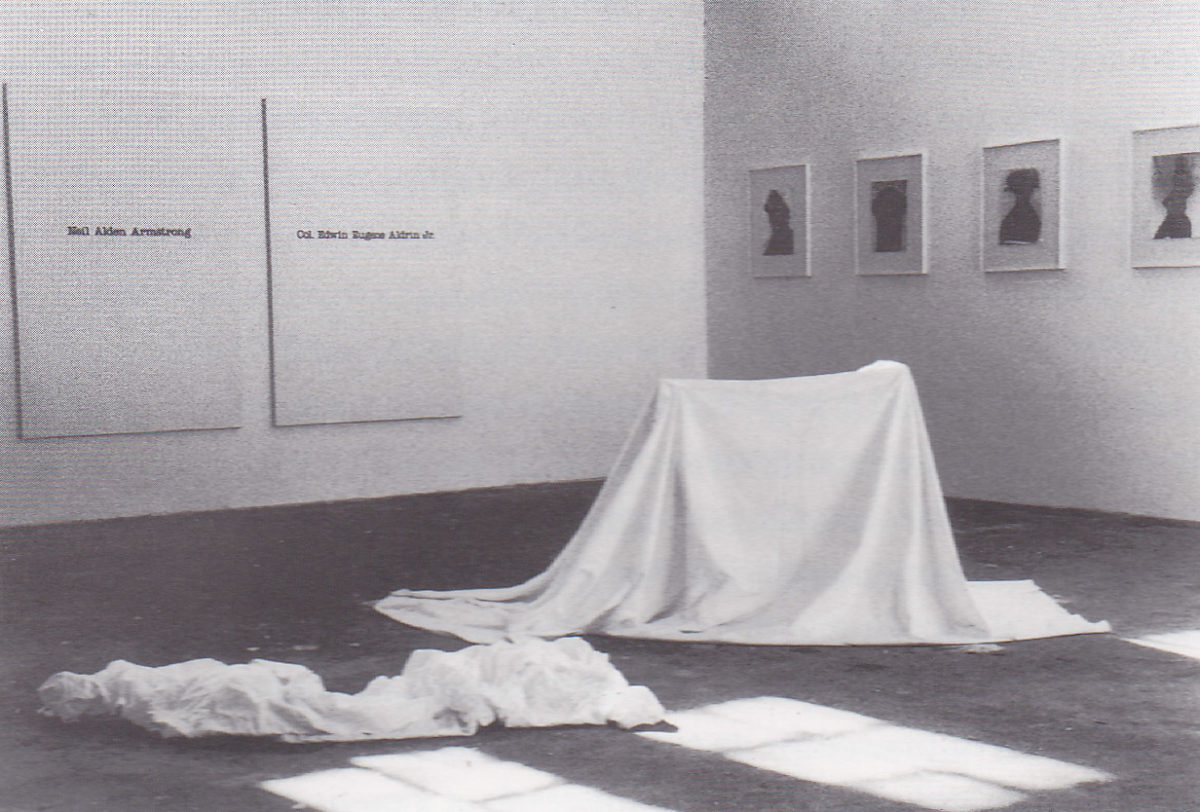

In the late 1980s British art entered what was quickly recognised as a new and excitingly distinctive phase, the era of what became known as the YBAs – the Young British Artists. Young British Art can be seen to have a convenient starting point in the exhibition Freeze organised in 1988 by Damien Hirst while he was still a student at Goldsmiths College of Art. Freeze included the work of fellow Goldsmiths students, many of whom also became leading artists associated with the YBAs, such as Sarah Lucas, Angus Fairhurst and Michael Landy. Goldsmiths College of Art played an important role in the development of the movement. It had for some years been fostering new forms of creativity through its courses which abolished the traditional separation of media.

This period marked a shift in the art world’s perceptions of young artists, attaching significantly greater value to their work with the attention of super collectors, and soon, institutions. Though perhaps the concentrated magnitude of the YBA movement has not yet been recreated, a continually growing interest in the work of young artists and recent art graduates ensued. Today it is not really a shock to see an artist a few years out of art school represented by a blue chip gallery. Of course there are numerous factors that come into play, largely social influences, that impact these allegiances, but it is worth noting that youth is not off-putting to a gallery as it might have been once.

Following the peak of this period, during the 90s, a similar but perhaps slower movement took grip on the fashion industry in London. In many ways, perhaps it is fair to observe that fashion mimics art. Fashion East is a pioneering non-profit initiative established by Lulu Kennedy and the Old Truman Brewery in 2000. Maintaining its position as one of most well respected platforms form emergent designers, the scheme champions young designers, showcasing them at London Fashion Week. As part of the scheme designers receive a bursary, a fully produced runway show and are taken to Paris to hold sales appointments with international stores. The scheme, and its menswear counterpart, has played a vital role in propelling the careers of many of London’s most influential brands, including Jonathan Anderson, Roksanda Ilincic, Simone Rocha, Craig Green, Grace Wales Bonner and Marques’ Almeida, among many others.

Our fascination with the output of the young is likely rooted in the sense of fresh enthusiasm and newness potentially imbued in the work, an unadulterated and optimistic point of view. Social theorists Chip Heath and Dan Heath talk of our first experiences, those which largely tend to occur between the ages of fifteen and thirty, playing a vital role in shaping our perceptions of the world and ultimately our creative outputs, positing that those who are able to innovate throughout life, are continually generating first experiences. In an oversaturated environment, perhaps it is this sense of capturing a first experience in some way, which draws the industry to continually younger talent.

It is also relevant at this point to acknowledge the impact of social media, particularly today of Instagram, in offering a greater sense of authorship and visibility to creatives who might have previously been waiting longer to find a platform for their work. There is undoubtedly strength in this democratic visibility, but with the veracious appetite for new images and new names, there is an underlying sense of a throwaway culture that is unavoidable. Names can be quickly propelled into a sphere of popularity, not necessarily correlating with financial sustainability, and just as quickly be replaced. This process is nothing new but the pace at which it moves, certainly within the context of London at present, is at times overwhelming.

In London, while there is a lot of focus on new graduates or even students, which is of course a positive thing, and a different type of excitement surrounding established houses, there is perhaps a middle ground of burgeoning mid-career designers and makers, those who didn’t necessarily receive the hype in the early stages but are producing work of value, who become overlooked. That is not to say there are no recent examples of designers who have stepped out on their own later in their careers and made great successes independently, but there does seem to be a London-specific sense of pressure which expects, or at least strongly encourages, a level of success to have been accomplished in your very early years to continue and grow as an independent agent. There are a number of initiatives which support creatives straight out of university but perhaps there should be more opportunities and platforms for those at a later point, placing youth on less of a pedestal and expelling the myth of an expiry date.

Feature image: Richard Quinn, Graduate Collection (via Central Saint Martins)