Interview: In The Studio With Artist Tschabalala Self

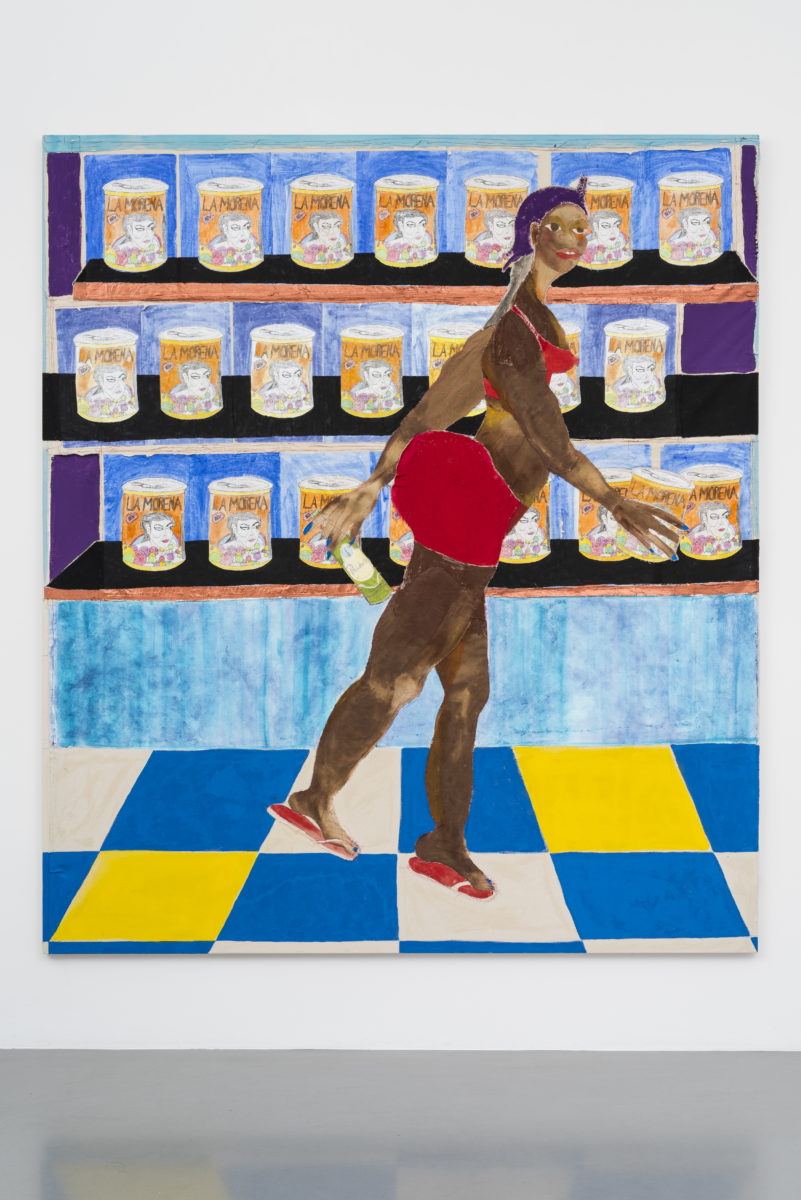

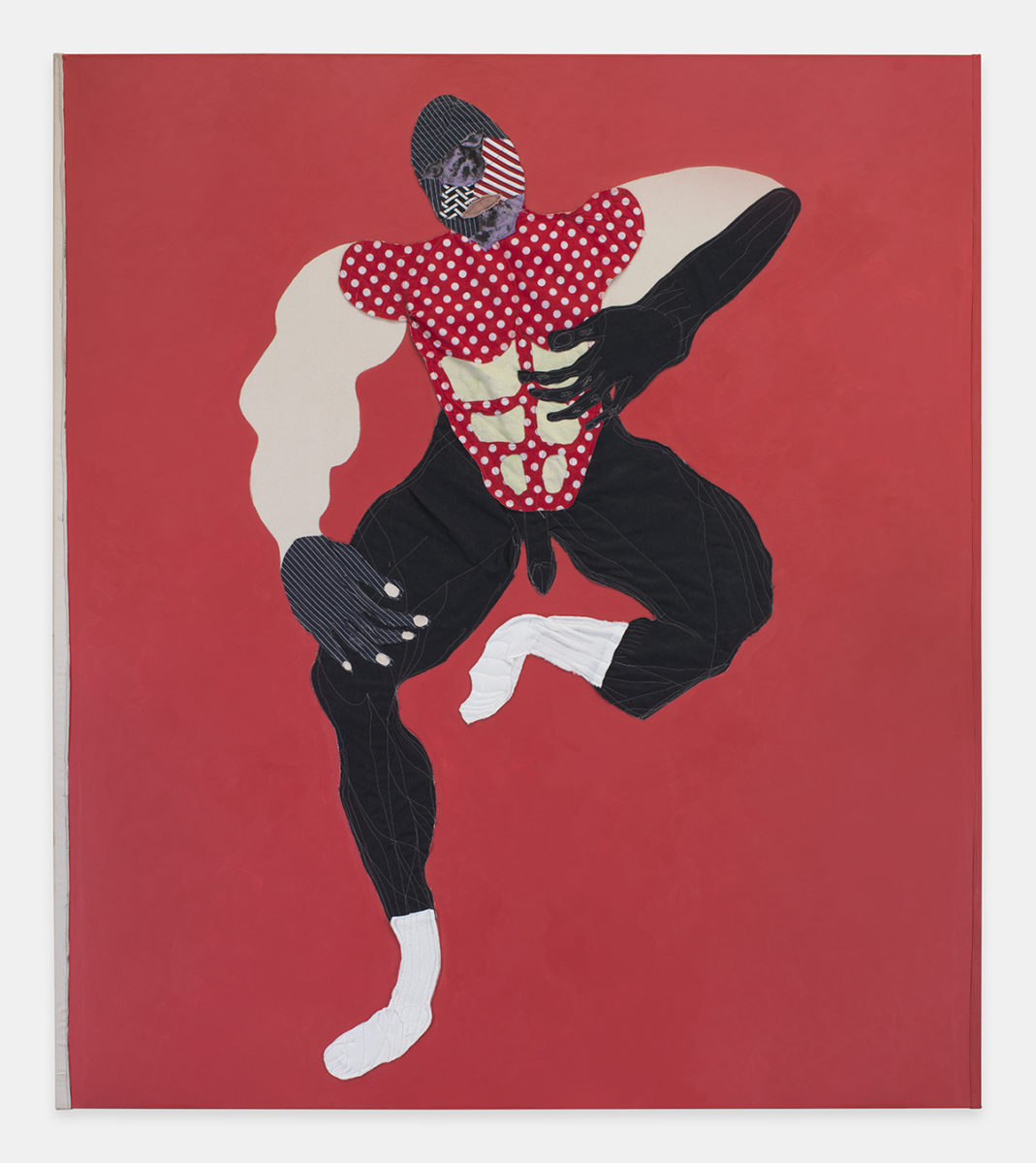

By Something CuratedAmerican artist Tschabalala Self’s expressive and dynamic works, which include painting, print, collage and sculpture, depict diverse human figures, and more recently, their surroundings. The fluidity of movement and exaggerated form of her images are quick to capture the attention of viewers and elicit a vivid response. Primarily concerned with the Black female body within contemporary culture, Self examines the confluence of race, gender and sexuality through a variety of forms and narratives. Working between Harlem and New Haven, Self’s recent works, exploring the socio-political site of the New York City bodega, are currently on show at Shanghai’s Yuz Museum. Something Curated spoke with the artist to learn more.

Something Curated: Can you give us some insight into your background? How did you enter this field?

Tschabalala Self: I’m from Harlem, New York. I went to Bard College for undergrad and Yale School of Art for my M.F.A, and I started showing my work professionally after graduate school; I had my first solo show with a gallery in 2015, Schur-Narula in Berlin.

SC: How did growing up in Harlem shape you?

TS: I’m not entirely sure. That’s where I grew up. If I grew up in a different place, my whole personality would be different. Harlem is a unique place and there is always something going on. I guess being in Harlem, it was mostly good for my self-esteem; it was good being surrounded by black culture and people as a child. Growing up in Harlem made me both ambitious and humble, cautious and brave.

SC: Your work explores diverse ideas about the Black female body; what are some of the specific issues you touch on?

TS: When I first started making work, it was a big deal for me to challenge other people’s ideas and correct other people’s thoughts about Blackness and femininity, or womanhood, or Black womanhood. At this point, I’m less concerned with changing other people’s ideas about this, and the public’s idea about the communities that I identify with. It’s more about creating images that can resonate with the communities I care about. That’s my main goal at this point. I can’t prioritise one aspect of my identity over another. However, I do want to create work that all people, specifically Black women, can see and feel moved by. That’s important to me. There are not a lot of examples for us, and the examples that do exist, I don’t find truthful or thoughtful.

SC: I discovered your work in London through the show at Parasol unit last year. Could you tell us about your thinking for the exhibition and what your experience was like working with the foundation?

TS: Working with the Parasol unit foundation for contemporary art was a good experience. It was the curator, Ziba Ardalan’s idea to bring those pieces together. It was really important for me, especially in retrospect, to have done that show at that time because I was able to see all of the work I had made thus far in my career. It was pretty much all of my early work and an extremely unique opportunity, a quarter-life retrospective.

SC: You often use a combination of sewn, printed, and painted materials, among other mediums – could you tell us more about your use of material?

TS: I kind of happened upon this process during experimentation in my studio. For a long time I worked with printmaking, but I moved away from works on paper because there were a lot of limitations with scale. I also wanted to find a way back to canvas. The printmaking process which I was using was a collagraphic one, and I would build my own plates, so I took that way of working and applied my process to painting. That’s how I happened upon the technique that I’ve developed to make my current body of work.

The paintings are comprised of many parts, and I try to find diversity in texture, depth and pattern through the use of unique materials. Those different parts are assembled to build the figures in the painting, primarily, and then more recently, the figures and the environment in my new series. My formal practice mirrors my thought process; my figures are literally and figuratively a sum of many parts. They are archetypal characters who represent a multiplicity of feelings and ideas. This is why they are built from disparate elements. You are the sum of your experiences, but you also absorb, in a lifetime, all of the different ideas and experiences of others. My process mimics this phenomenon.

SC: Can you tell us about the Bodega Run show currently open at The Yuz Museum in Shanghai?

TS: Bodega Run at The Yuz Museum is part of a series I’ve been working on about New York City bodegas, and the project has a couple of different parts. Initially, I was intrigued by the bodega’s aesthetic; visually, I found it fascinating as a space. The bodega occurred to me as a plausible environment in which I would find one of my characters, if I were to encounter them in real life. My older works usually depicted one figure floating in a liminal space, and I felt like I wanted to challenge myself to place my figure within an environment. A lot of the characters I had built in my previous works, were characters that could, in many ways, represent a larger community. The bodega felt similar as a type of environment. Even though it was one space, within that space, was mirrored the community outside of it. By unpacking the social significance and function of this one store I was able to have a larger conversation.

The histories behind these stores are important to understand, and speak to the ways in which the communities surrounding the bodegas have been systematically deprived. The reason why bodegas exist is because there weren’t many places to get food; there weren’t many supermarkets or restaurants; there wasn’t anything like that for a long time. Bodegas exist in communities that were economically depressed and coloured. Food deserts and issues surrounding food equity are paramount in understanding the phenomenon of the bodega. These stores sell everything: socks, Band-Aids, Tylenol, and they have ATM’s. They sell all of these things because there is need for these products and no commercial infrastructure to support these needs.

While working on my project, a lot of other ideas started to occur to me. I began to realise that the bodega is a unique space, in that it’s a store that is owned primarily by people of colour that serves communities of colour, which is rare in the American Northeast. In the past, I’ve spoken about wanting to create this vacuum within my practice in which to talk about identity, where Blackness could be discussed through a lense of Blackness and not placed in relation to the Other. The bodega existed as a real life model where I can speak about diversity, and there is no need to talk about Whiteness. The bigger question at hand is what can a store tell you about a community, and what can a transactional space tell you about the people that interact with it?

SC: What has your experience been like as a Harlem Studio Museum artist-in-residence?

TS: It’s been really good; I’m happy to be back home. I have never had a studio in Harlem before. I get so many ideas walking around the neighbourhood, and it’s nice to be able to put those ideas into practice.

SC: Are there upcoming projects that you’re working on that you’re able to tell us about?

TS: The show at the Studio Museum will be in 2019, and details will be announced soon.

SC: Are there any artists or people from different fields who have particularly influenced you in your career?

TS: Faith Ringgold is one of my favourite artists. I also like David Hammonds, Nari Ward, Clementine Hunter and Howardena Pindell, to name a few. I’ve been thinking a lot about Donald Goins recently, he is my favourite hood-storyteller.

SC: What do you enjoy about working between the city and New Haven?

TS: New Haven is nice because it’s really affordable. I also like New Haven because it’s a very Black city, and that’s super inspiring to me. I live in the Hill, and it reminds me of how Harlem used to be. My neighbourhood back home has changed. People say that Harlem is all White now, but that’s not really true. I think people say that partially because they want to farther that narrative, and want that to happen, but that’s not really the issue, it’s just more that it’s changed in a lot of ways. A lot of the neighbourhood institutions aren’t there anymore, like the Mom and Pop stores.

The community is more transient; it used to be a lot of people who lived there for their whole lives, people that raised their whole families there, but they don’t really have those communities there any more, it’s more in and out. It doesn’t have the same energy that it used to have, and it’s not so exciting to me anymore – New York feels more like an office to me now. It’s nice to come to a smaller community like New Haven and feel like you are part of something where people have real roots. I still have my family in Harlem, and I still spend a lot of time there, but it’s just different. The same but different.

SC: Favourite arts spaces in NYC?

TS: Number one is the Studio Museum in Harlem. I also love the Whitney, the Schomburg in Harlem, MET Breuer and MoMa PS1 – those are all good.

SC: Favourite restaurant in NYC?

TS: I am a little scared to say, because I do not want too many people going, but The Grange on 141st and Amsterdam. I’ve been going there for years. But Touch of Dee is the best old school spot.

SC: What are you currently reading?

TS: Right now, I am reading Inside the White Cube by Brian O’Doherty.

Interview by Keshav Anand | Feature image: Sunday, 2016 (All images courtesy Tschabalala Self)