Black Artists Challenging The Subjugation Of Black Bodies

By Something CuratedSpanning centuries, Black artists have shared powerful portrayals of the strife and triumphs of African Americans through diverse and compelling works. From pioneers like Augusta Savage and Jacob Lawrence, to Jean-Michel Basquiat and Kara Walker, these creators have helped illuminate critical social and political issues, reflecting upon and challenging the mistreatment of Black bodies.

Determined to become an artist, Augusta Savage, then Augusta Christine Fells, arrived in New York in 1921. She completed her studies at Cooper Union within three years, supporting herself with a job as an apartment caretaker. New York Public Library shortly after commissioned her to produce a bust of William Edward Burghardt Du Bois, the first in a series of leading African American figures. These meetings were to have a strong impact on the artist, who became a formidable activist. In 1923, excluded from a study programme in France due to the colour of her skin, she confronted the admissions committee, becoming the first African American woman to defy the art world. Having dedicated her work to the fight for civil rights, even to the detriment of her own artistic career, Augusta Savage is today a legend of the Harlem Renaissance.

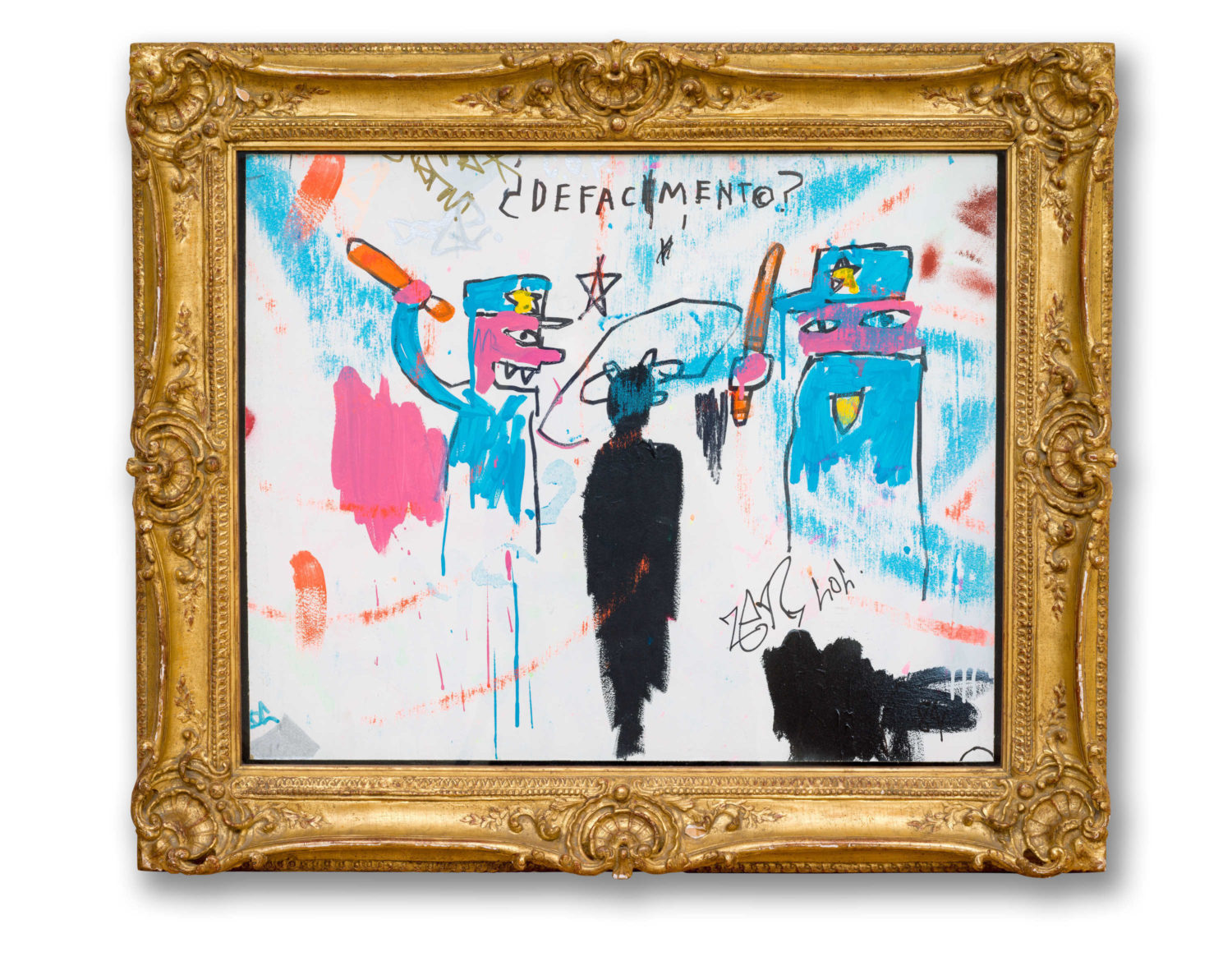

Jean-Michel Basquiat’s The Death of Michael Stewart, informally known as Defacement, was created by the artist in 1983. The work commemorates the fate of the young, Black artist Michael Stewart at the hands of New York City Transit Police after allegedly tagging a wall in an East Village subway station. Originally painted on the wall of Keith Haring’s studio within a week of Stewart’s death, Basquiat’s painting was a deeply personal lamentation. The artist’s dense practice explores diverse aspects of Black identity, including his protest against police brutality and his canonization of historical Black figures, especially the jazz legend Charlie Parker, who was perhaps Basquiat’s favourite hero to depict on canvas. He also maintained a sustained engagement with the subject of state authority in several paintings, depicting ominous police figures.

American artist and filmmaker Kara Walker is perhaps best known for her room-size tableaux of black cut-paper silhouettes. A Subtlety, also known as the Marvelous Sugar Baby and subtitled an Homage to the unpaid and overworked Artisans who have refined our Sweet tastes from the cane fields to the Kitchens of the New World on the Occasion of the demolition of the Domino Sugar Refining Plant, is a 2014 piece by the artist. A Subtlety was dominated by its central piece, a white sculpture depicting a woman with African features in the shape of a sphinx, but also included fifteen other sculptures. These fifteen “attendants” to the sphinx were enlarged versions of contemporary blackamoors produced in China. The piece was installed in the Domino Sugar Factory in the Williamsburg neighbourhood of Brooklyn from May through July 2014. The controversial exhibition sparked conversations about the show’s audience, the gentrification of Brooklyn, and the work’s themes of race, sexuality, oppression, labour, and the ephemeral.

Artist Sherman Fleming, who also worked under the pseudonym RODFORCE, has been actively involved in performance art since the 1970s. In the mid-1980s he abandoned his alias, feeling that its allusions to historic stereotypes about Black male sexuality and virility had run their course. His work often explores the body’s expressive power and the limits of endurance, confronting issues of Black masculinity and the psychosexual tensions surrounding the Black male body. In Pretending to Be Rock (1993), the artist, positioned on his hands and knees, surrendered his semi-nude body to the dripping of hot wax, which fell from a makeshift candelabra holding dozens of burning candles above him. In using his back as the site of trauma, Fleming evoked the iconic image of the former slave Gordon, who escaped to the Union Army and whose scars told the traumatic story of chattel slavery.

Working today between Harlem and New Haven, American artist Tschabalala Self’s expressive and dynamic works, which include painting, print, collage and sculpture, depict diverse human figures, and more recently, their surroundings. Primarily concerned with the Black female body within contemporary culture, Self examines the confluence of race, gender and sexuality through a variety of forms and narratives. In a past interview with Something Curated, Self explained: “When I first started making work, it was a big deal for me to challenge other people’s ideas and correct other people’s thoughts about Blackness and femininity, or womanhood, or Black womanhood. At this point, I’m less concerned with changing other people’s ideas about this, and the public’s idea about the communities that I identify with. It’s more about creating images that can resonate with the communities I care about.”

Fellow Harlem-based interdisciplinary artist Sanford Biggers’ work is an interplay of narrative, perspective and history that speaks to current social, political and economic happenings while also examining the contexts that bore them. His diverse practice positions him as a collaborator with the past through explorations of often overlooked cultural and political narratives from American history. Working with antique quilts that echo rumours of their use as signposts on the Underground Railroad, he engages these legends and contributes to this narrative by drawing and painting directly onto them. In response to on-going occurrences of police brutality against Black Americans, Biggers’ BAM series is composed of bronze sculptures recast from fragments of wooden African statues that have been anonymised through dipping in wax and then ballistically “resculpted.”

Love Is The Message, The Message Is Death, 2016, a video by artist, director, and cinematographer Arthur Jafa is set to the searing highs and lows of Kanye West’s gospel-inspired hip-hop track, “Ultralight Beam.” Love Is The Message is a masterful convergence of found footage that traces African American identity through a vast spectrum of contemporary imagery. From photographs of civil rights leaders watermarked with “Getty Images” to helicopter views of the LA Riots to a wave of bodies dancing to “The Dougie,” the meticulously edited 7-minute video suspends viewers in a swelling, emotional montage that is a testament to Jafa’s profound ability to mine, scrutinise, and reclaim media’s representational modes and strategies. While the work poignantly embodies the artist’s desire to create a cinema that “replicates the power, beauty and alienation of Black Music,” it is also a reminder that the collective multitude defining Blackness is comprised of singular individuals, manifold identities and their extraordinary differences.

Feature image: Sanford Biggers, Selah, Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York, 2017 (via Marianne Boesky Gallery)