Interview: Hannah Quinlan & Rosie Hastings On The Politics, Histories & Aesthetics Of Queer Spaces

By Something CuratedLondon-based artists Hannah Quinlan and Rosie Hastings’ first solo institutional exhibition In My Room, installed at MOSTYN and running until 18 April 2021, brings together diverse mediums from film, fresco painting and works on paper. As a new body of work, In My Room develops the artists’ inquiry into the politics, histories and aesthetics of queer spaces and culture, building upon the duo’s project UK Gay Bar Directory (UKGBD), 2016, a moving image archive of gay bars in the UK made in response to the systematic closure of LGBTQA+ dedicated spaces. To learn more about the works included in the compelling new show, Quinlan and Hastings’ collaborative relationship, and how they have handled life during the pandemic, Something Curated spoke with the artists.

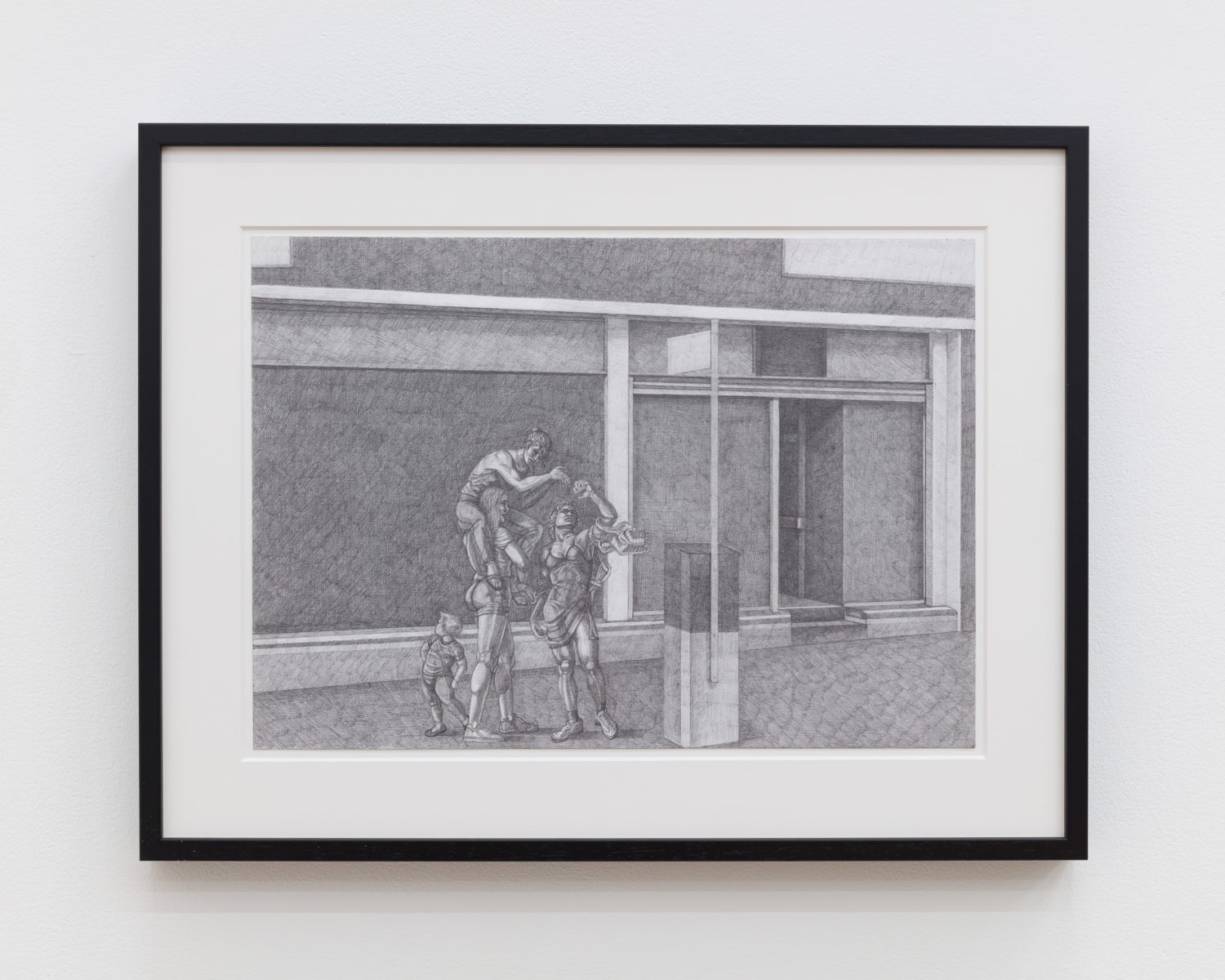

Boltz, 2020. Graphite on paper. Courtesy the artists and Arcadia Missa.

Something Curated: What is the thinking behind your current exhibition In My Room at MOSTYN?

Hannah Quinlan + Rosie Hastings: In My Room explores UK male sex culture, linking this to a broader phenomenon of male dominance within society and thinking socially and historically about how public sex culture has shaped and gendered urban architecture and public space. We wish to disrupt contemporary discourse that situates public sex culture within “radical” queer practice; we were thinking about the ways in which this culture reinforces rather then disrupts power structures of gender, class and race. We were asking questions such as: who gets to take risks? Who is allowed agency over their own pleasure? How to be visible without being exploited? How to lay claim to public space?

The title of the exhibition and film In My Room comes from the song first released by Nancy Sinatra and later covered by gay icon Marc Almond. We were considering how the sphere of men’s private and personal space stretches from the private (a bedroom) to the public (a sex club), and that in a sense the whole world is a man’s bedroom to use how he pleases. We were drawn to Birmingham’s gay village as a primary location for the film; we first visited the village in 2016 whilst filming the UK Gay Bar Directory. In 2016 Birmingham had a robust gay scene that seemed uniquely unaffected by the rapid spate of gay bar closures spreading through the UK. We returned to Birmingham because its gay scene was so heavily dominated by male-only venues. The Birmingham we returned to in 2019 was very different from the one we visited in 2016.

Homogeneous luxury apartment blocks in various states of completion spread over the gay village, the barren land separating the gay bars from the town centre was now stripped and divided into multiple construction sites. Every single men-only venue had either closed or was scheduled to close in the coming year. The village was being gentrified in anticipation of the highly politicised HS2, a high-speed rail line connecting London and Birmingham. This complicated our project; we were representing these spaces of male power at a moment of vulnerability and change, and we felt a responsibility to use our film to archive and uphold these venues as we critiqued them. It feels important to note that we are not advocating the closures of male-only spaces nor are we opposed to sex in public. We are interested in exploring how male-only spaces and public sex between men has ramifications culturally, socially and politically and in proposing strategies for a redistribution of this power.

The exhibition features a wall rubbing taken from the facade of Bar Jester, a historic gay bar in Birmingham that also features in the film – at the time of filming the venue had closed. The show also featured a series of graphite drawings showing venues that had recently closed or were facing planned closure in the near future. We stripped back the architecture of the venues depicting them without their signage, and outside the venues groups of women congregated playing and fighting. We have a long-term interest in how an archive manifests materially and conceptually; we were imagining these works on paper as possible extensions of the UK Gay Bar Directory as well as meditations on these unique venues. The two large framed rubbings, a technique popularised by the Victorians who made rubbings of graves, felt like an appropriate medium to memorialise Bar Jester.

The show also features a large fresco painting on wooden boards called Republic. It was the first time we have worked in this ancient technique and studied the method on a weeklong workshop with fresco artist Fleur Kelly in Toulouse – it was incredibly materially complex to produce. The composition for Republic was informed by Flagellation of Christ, with the Pavement by Andrea Mantegna, an all-male scene of Christ being whipped by Romans. We were inspired not only by the extreme melodrama of the scene and characterisation but also by the fact that this was taking place on the pavement, in a very public area. One of our exhibition’s primary concerns was the ways in which public space in a Western and, specifically UK context, is dominated by white men both socially, culturally and economically and how elements of men’s public sex culture are representative of this domination.

We were provoked by a question once posed to us on a panel – what would a woman-dominated public and an ensuing women-only public sex culture look like? It felt like a proposition somewhere just beyond the imaginable. With Republic we imagined this scenario whilst veering away from utopian and naive visions of a female-dominated society as inherently caring and non-violent. We were thinking of real-world issues that define women’s space and culture: infighting, racism, homophobia and transphobia. The melodrama of Mantegna’s etching felt like the perfect premise on which to base our composition – fractious individuals engaged in conflict and languid onlookers who all fiercely occupy the space of the pavement with larger than life strength and presence. Not only is it an inversion of Mantegna’s etching, men to women, but also of the ways women are traditionally conditioned to occupy public space – to be small, quiet and afraid.

SC: How would you describe your collaborative dynamic?

HQ + RH: We share everything and our collaboration is an extension of our love for one another; we started collaborating because we couldn’t bear being apart and we have worked together ever since. We have had to learn to diminish our individual egos and overcome our fears regarding authorship in art-making. At first this was incredibly difficult and we had daily conflicts in the studio, now our collaboration is almost seamless and we have developed a way of working that feels very natural. We challenge one another and force each other into difficult spaces with our work; we teach one another and it’s this channelling of collective resources, both mental and physical, that allows us to work prolifically in so many different mediums.

SC: What motivated the UK Gay Bar Directory (UKGBD) project in 2016 and why is it still so important?

HQ + RH: The UK Gay Bar Directory is a moving image archive of gay bars in the UK, featuring over 100 gay bars and filmed in 14 different cities over a period of nine months between 2015-2016. We made the directory in response to the rapid closure of gay bars in the UK. The directory was intended both as an art work and an educational resource; we wanted to document these disappearing spaces, both as a blueprint of queer space and also to understand what the closures meant for broader LGBTQ culture and question why these closures were occurring. The UKGBD is our foundational work and a resource that we return to time and time again. Whilst travelling the UK we encountered so many fantastical and unique spaces and met numerous people along the way. At the time, we were incredibly focused and absorbed a vast amount of information in a short space of time.

Making films such as Something For The Boys (2018) and In My Room gave us the opportunity to zone in on specific places such as the Blackpool gay scene (where Something For the Boys is shot) and Birmingham. Making films became a way of committing more time and research to a particular place. When we filmed the UKGBD we began to see these gay bar closures as part of a wider attack on public space by the conservative led government, who wielding a destructive policy of austerity was and still is rapidly dismantling state infrastructure and public services. In 2020, as a recession induced by the global pandemic looms these issues are more relevant than ever.

Unit 2, 2020. Graphite on paper. Courtesy the artists and Valeria and Gregorio Napoleone collection, London

SC: Can you expand on your use of dance and the performing body in your new video work?

HQ + RH: For In My Room we worked with the iconic choreographer Les Child; together we worked through masculinity as a series of codes, gestures and behaviours. Public-sex spaces largely function non-verbally, We reimagined non-verbal communication in the gay club as a dance used to assert dominance and submission, desire and tension. The dances reference the classic line dance – a dance where the group follows a series of prescribed movements dictated by a leader – we were thinking about the reproduction of movement as the reproduction of masculinity in space. Les developed a series of movements to help the dancers get into character but much of the final material was improvised; it was important to leave the performers room for their own feeling in the role especially considering how intimate much of the footage is.

In the final scene of the film we see Lucille Marshall, an incredible dancer, performing on the pole. This scene was intended as a sort of upheaval or crisis in the film as a whole. With Lucille’s scene, we were thinking about how women’s access and inclusion in public sex culture has been dependent largely on their labour as workers – sex workers, escorts, strippers, etc., as opposed to their custom. We were also thinking about how public sex spaces are designed or chosen to heighten a feeling of risk. As artists we are drawn to dance because of its rich history in relation to queer culture. At a time when the community was heavily censored, policed and criminalised, dance became a vehicle of self-expression both on the stage and screen but also on the streets and dance floor. We are interested in these different dance registers – both professional and colloquial to explore dance as a world-making, identity-forming and community-building resource within queer life and history.

SC: What are you working on at present, and how has the pandemic affected your way of operating?

HQ + RH: In the space of three weeks, we opened the exhibition Public Affairs at Isabella Bortolozzi Galerie, Berlin, In My Room at MOSTYN, and also co-won the Jarman award for artist filmmakers. We are now taking some much needed time off; it’s our first substantial break in two years and we will be spending it like most of the world in lockdown. As our work is very studio intensive, it’s important to use our time off to get as far away from the studio as possible, as that isn’t an option right now we will be reading, spending time together and gathering strength for our next project.

Hannah Quinlan and Rosie Hastings: In My Room | 14 November 2020 – 18 April 2021

Exhibition temporarily closed from Saturday 5 December 2020 due to new Covid-19 restrictions in Wales — see here for updates.

Feature image: Hannah Quinlan and Rosie Hastings, In My Room, 2020. HD Video. Installation at MOSTYN, November 2020. Courtesy the artists, Arcadia Missa and Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi. Photo: Mark Blower.