Interview: MOS Architects’ Michael Meredith & Hilary Sample On Embracing Difference

By Something CuratedEstablished in 2003 by Michael Meredith and Hilary Sample, New York-based architectural practice MOS Architects’ fascinating and eclectic body of work oscillates between diverse outputs from housing, educational sites, cultural institutions and retail spaces, to exhibitions, installations, furniture, and objects; the practice also regularly produces books, speculative software and films. Their distinctive approach to design champions an off kilter aesthetic while effectively taking into consideration pragmatic factors from tumultuous economic climates to environmental conditions. Utilising forward-thinking digital technologies to create variable environmental scenarios, the firm’s projects offer experimental solutions to pressing problems. To learn more about how MOS came to be, what Meredith and Sample are working on at present, and how the pandemic has impacted their operations, Something Curated spoke with the architects.

Something Curated: Can you give us some insight into your respective backgrounds and how you entered the field of architecture?

Michael Meredith: I’ve known Hilary as long as I’ve known architecture. We met on the first day of undergraduate school when we were 17. I grew up in upstate New York in a somewhat suburban area. I didn’t know what I wanted to study when applying to college, so I applied for random things. Philosophy, economics, liberal arts, chemistry… it was totally random and unfocused. My father is an engineer and suggested architecture. I went along with it.

Hilary Sample: I’ve always been interested in both buildings and making things. I grew up in Eastern Pennsylvania on the edge of an apple orchard and farms, but within an hour drive to New York City and Philadelphia. My mother had lived in the City, working as a nurse at Cornell, and would talk about living in the hospital. I always thought that was strange and exciting. She took me on my first trip to New York, and from there I became interested in housing and women’s work in the City. My upbringing was modest; I was an only child and spent a lot of time drawing. I enjoyed making things with found objects, recycling them into toys and structures. My mother is an extraordinary craft maker, very detailed and into patterned fabrics. There are other influences, but it converged. When I was in high school, I tested for sciences and art, but was discouraged by guidance counsellors, who said it was for men, not girls. This made me want to do it more. I’ve never been big on being told I can’t do something!

SC: How would you describe the ethos of MOS Architects and your collaborative dynamic?

MM: There’s a certain amount of chaos you get used to when running a small office. It is difficult to describe. It changes constantly. It’s inconsistent. One day we are simultaneously making furniture, answering emails, talking with engineers, doing code compliance checks, writing a text, doing a competition, and so on. The next day is different. In general, both of us are on all correspondences about office stuff; we stay involved throughout the process at all levels. This is definitely not ideal from a business delegation perspective, in some ways it’s exactly the wrong thing to do, but we like the process of making things together. Even the frustrations of it. That said, the office definitely changes and shifts with different people in it. Because we’re so small, one person can change the entire dynamic. The ethos, ethic, we suppose is a sort of flatness, a sort of chaos, a sort of constant making of different things simultaneously.

HS: We’re trying to work within a certain set of things – furniture, books, objects, videos, software, etc. – and buildings, questioning how they can be reimagined through a particular economy and way of making that is repeated and becomes known to us. We make a lot of things, full-scale tests, and live with them.

SC: Can you tell us about your project Lali Gurans in Kathmandu, Nepal?

MM + HS: In 2010, we began working with an amazing NGO to build a community centre, library, house, garden, and orphanage. The site was rural, on an edge of Kathmandu that was being urbanised rapidly. And seismic. We designed it with AKT in London, who were adamant about it being prepared for earthquakes. We designed it to one level below a nuclear reactor. There were actually two major earthquakes in 2015 that it withstood while it was under construction. The frame is reinforced concrete, sloping inward to withstand any possible shaking. Stairs double as cross bracing, further stabilising things. Still, it was important for it to be light and open. When you move through the building, you are quickly inside, outside, then inside again. It’s somewhere between a building and a park. Some stairs are open-air. For wandering around the exterior frame, alongside vertical gardens. The building produces food. The other stair is interior, a vertical shaft with glazing on top for passive cooling. For efficient movement up and down. It’s being used currently although incomplete. We just spoke with Kishor, who is running the project in Nepal; things are difficult at the moment, but still on-going.

SC: What are you working on at present and how has the pandemic affected your way of operating?

MM + HS: In a way, how we work hasn’t changed that much. We are more remote than usual, but we always have done things through chats, text messages, email, shared drives, shared documents. We still sketch in notebooks, usually sending them as photos. More and more, we find ourselves screenshotting things in progress and drawing notes on top of them with our clumsy fingers using fat lines. It isn’t very precise. Somehow it works. Nowadays our lives seem to just be an assortment of shared drives and Google docs that we write in. Every project, every text, everything seems to have a shared document and drive associated with it. Our current work includes a shared house for two families, an exhibition at Maniera in Brussels, two affordable housing projects in Washington, DC that are under construction, a book researching the causes of retail vacancies in New York City and imagining new ways to use them, among others.

SC: MOS Architects’ homes possess a very particular and recognisable physical presence — could you expand on your interest in and approach to designing a residential space?

MM: It’s hard for us to see our work as you see it, we’d love to hear more about what you mean. Like many practices in the US, we started with houses, furniture, research, drawings, thoughts, fragments. You start however you can and go from there. Beginning in smaller scale fragments is essentially beginning with the domestic interior. That said, we’re interested in buildings beyond houses, we just haven’t had much opportunity to do them. The few schools and education-type spaces we have done are very important to us.

HS: Traditionally, building an architecture practice emphasised doing new buildings and things as a whole, as opposed to only parts – we came to work on interiors and apartments only after working on the whole. We are always questioning every aspect of what it requires to make and maintain a space that’s lived in. Even if they perform a different function than something like a school does, houses are buildings at the end of the day and are quite complex in their programming and performance. It’s a cliché to say that once you have designed a house, you can design anything, but it’s true. There is a sensitivity to so many things when designing a house, which are lessons that can be reimagined for a public building. Our houses and buildings are made with efficiency and a sense of restraint overall, finding moments of playfulness.

SC: You’ve created numerous compelling publications over the years — what attracts you to bookmaking as a medium?

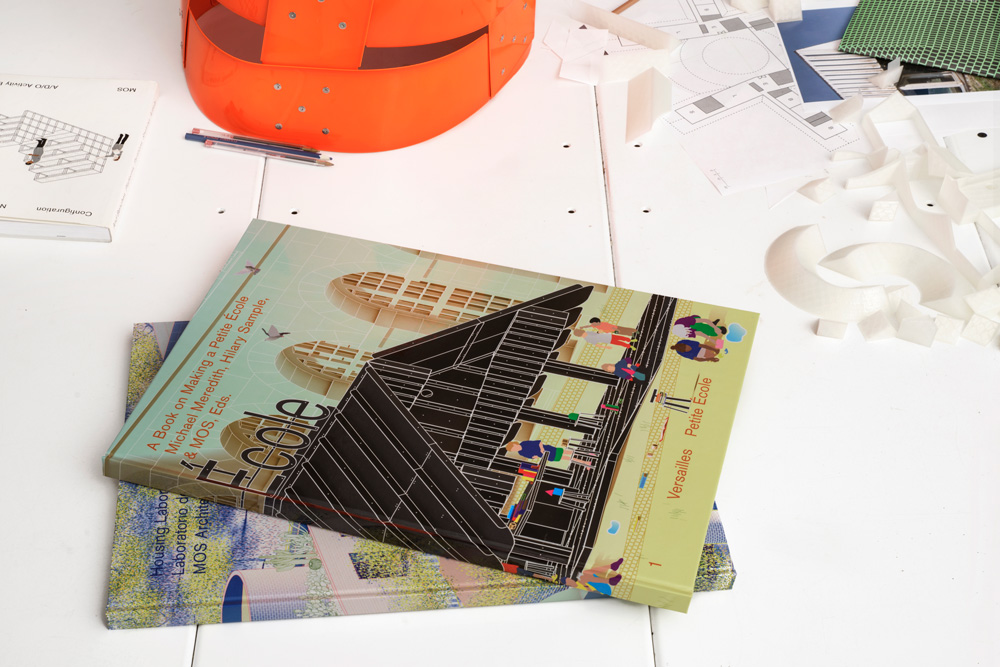

MM + HS: We have always loved books, and it’s hard to explain our love. Maybe it’s the intimacy of them, we aren’t exactly sure. The materiality of them and care required to make one. We are constantly reading and looking at other people’s books. We like telling stories. The last book we made was Houses for Sale, which is a children’s book about looking for a new house. It was designed by Studio Lin, a talented graphic design office who we often collaborate with, and published with the Canadian Centre for Architecture. Recently, we’ve made these large books for School No. 3 (Petite École) and Housing No. 8 (Laboratorio de Vivienda) that we haven’t published yet.

SC: What do you want to learn more about?

MM + HS: We spend a lot of time in nature with our children – drawing, collecting, walking – and we’re interested in continuing to learn more about the natural world. We’re also spending a lot of time on music. Writing songs, learning new musical objects. It’s wonderful to live with and use them to fill the house with sound.

Feature image: House No.5 (Element House), Star Axis, New Mexico. Photo: Florian Holzherr. Courtesy MOS Architects