The Afro-Caribbean Jeweller Who Made Modernist Jewels For Duke Ellington & Eleanor Roosevelt

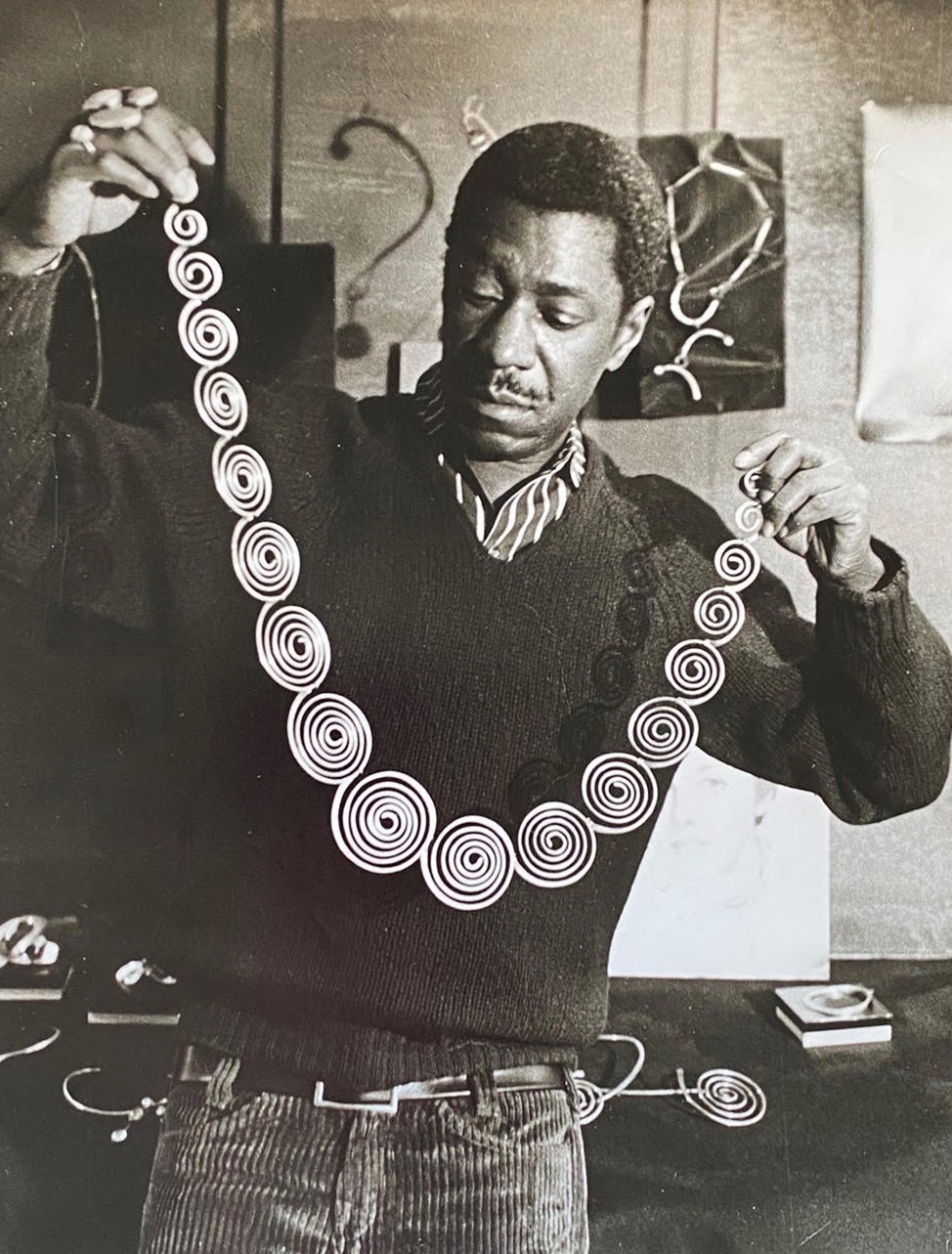

By Something CuratedArthur George ‘Art’ Smith, better known by Art Smith, was a leading modernist jeweller of the mid-20th century, and one of the few Afro-Caribbean creatives working in the field to reach international acclaim. Inspired by biomorphism and primitivism, Smith’s jewellery is dynamic and diverse, varying dramatically in size and form. His designs were influenced by Alexander Calder, Surrealism, African sculpture, and tribal jewellery and reflected the bohemian life of New York’s Greenwich Village in the 1940s and 1950s. Of his work, he once said, “A piece of jewellery is in a sense an object that is not complete in itself. Jewellery is a “what is it?” until you relate it to the body. The body is a component in design just as air and space are. Like line, form, and colour, the body is a material to work with. It is one of the basic inspirations in creating form.”

Born to Jamaican parents in Cuba in 1917, Smith’s family settled in Brooklyn, New York in 1920. From an early age Smith showed artistic talent, winning honourable mention as an eighth grader in a poster contest held by the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. Encouraged to apply to art school, he received a scholarship to Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art. He was one of only a small number of Black students at the institution, and his advisors tried to steer him towards architecture, suggesting he might readily find a job in the civil sector. His lack of interest in mathematics eventually led him to desert this path, and he turned to sculpture, gaining an education that would prove to be extraordinarily valuable.

After graduating in 1940, Smith got a job working for the National Youth Administration and later for Junior Achievement, an organisation devoted to helping teenagers find employment. He also took a night course in jewellery-making at New York University. This eye-opening experience, along with his close friendship with Winifred Mason, an African-American jeweller who became his mentor, set him on the course of his adult artistic life. Mason had a small jewellery studio and store in Greenwich Village, and Smith became her full time assistant. He subsequently moved from Brooklyn to the Village’s Bank Street. In 1946 Smith opened his own studio and shop on Cornelia Street.

A predominantly Italian locality at the time, Smith sadly endured racial violence from some of his neighbours. Alongside regular instances of hateful graffiti, and unfriendly altercations, his storefront windows were shattered on one occasion. Soon after, he relocated to 140 West Fourth Street nearby Washington Square Park, the heart of Greenwich Village where as an openly gay Black artist he felt more at home. It was from these headquarters that Smith’s career really began to burgeon. In addition to selling from this new location, he started to sell his jewellery to shops in Boston, San Francisco, and Chicago, and by the mid-1950s he had business relationships with prominent retailers like Bloomingdale’s and Milton Heffing.

A seminal influence on Smith’s career was the young Black dancer and choreographer Tally Beatty, who introduced the jeweller to the dance world “salon” of Frank and Dorcas Neal. Through Beatty, Smith rubbed shoulders with eminent Black artists including writer James Baldwin, composer and pianist Billy Strayhorn, singers Lena Horne and Harry Belfonte, actor Brock Peters, and expressionist painter Charles Sebree. Smith also began to design jewellery for several avant-garde Black dance companies, including, in addition to Beatty’s own, those of Pearl Primus and Claude Marchant. These commissions encouraged him to design on a grander and more theatrical scale than he had ever done previously.

In the early 50s, Smith received prominent coverage in Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar and was mentioned in The New Yorker shopper’s guide, cementing his profile. By the 60s he had begun to use a lot of silver in his jewellery, and as his client base increased so did the demand for his custom designs. He received several prestigious commissions, designing a brooch for Eleanor Roosevelt, and making cufflinks for Duke Ellington that incorporated the first notes of the musician’s famous 1930 song Mood Indigo. In 1969 he was honoured with a solo exhibition at New York’s Museum of Contemporary Crafts, today the Museum of Arts and Design, and in 1970 he was included in Objects: USA, a travelling exhibition curated by Lee Nordness, an influential crafts dealer.

Smith had had a heart attack in the 1960s, and by the late 1970s his health had seriously deteriorated. His shop on West Fourth was closed in 1979 and the pioneering jeweller passed away in 1982. Following his death, three major exhibitions were organised celebrating his life and work: Arthur Smith: A Jeweler’s Retrospective at the Jamaica Arts Center in Queens, 1990; Sculpture to Wear. Art Smith and his Contemporaries at the Gansevoort Gallery, 1998; and From the Village to Vogue at the Brooklyn Museum, 2008. To discover more, the definitive collection of all the artist jewellers of Smith’s generation is sumptuously illustrated in the volume Messengers on Modernism American Studio Jewelry 1940-1960, authored by Toni Greenbaum published by Flammarion and the Montreal Museum in 1996.

Bibliography:

From the Village to Vogue: The Modernist Jewelry of Art Smith, 2008, Brooklyn Museum

Fran Schreiber, A Review of ‘From the Village to Vogue: The Modernist Jewelry of Art Smith’, 2008, Ornaments and Objects

Art Smith, 2015, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, Smithsonian Institution

Feature image: Art Smith, ‘Loop Neckpiece’, 1950 (via Pinterest)