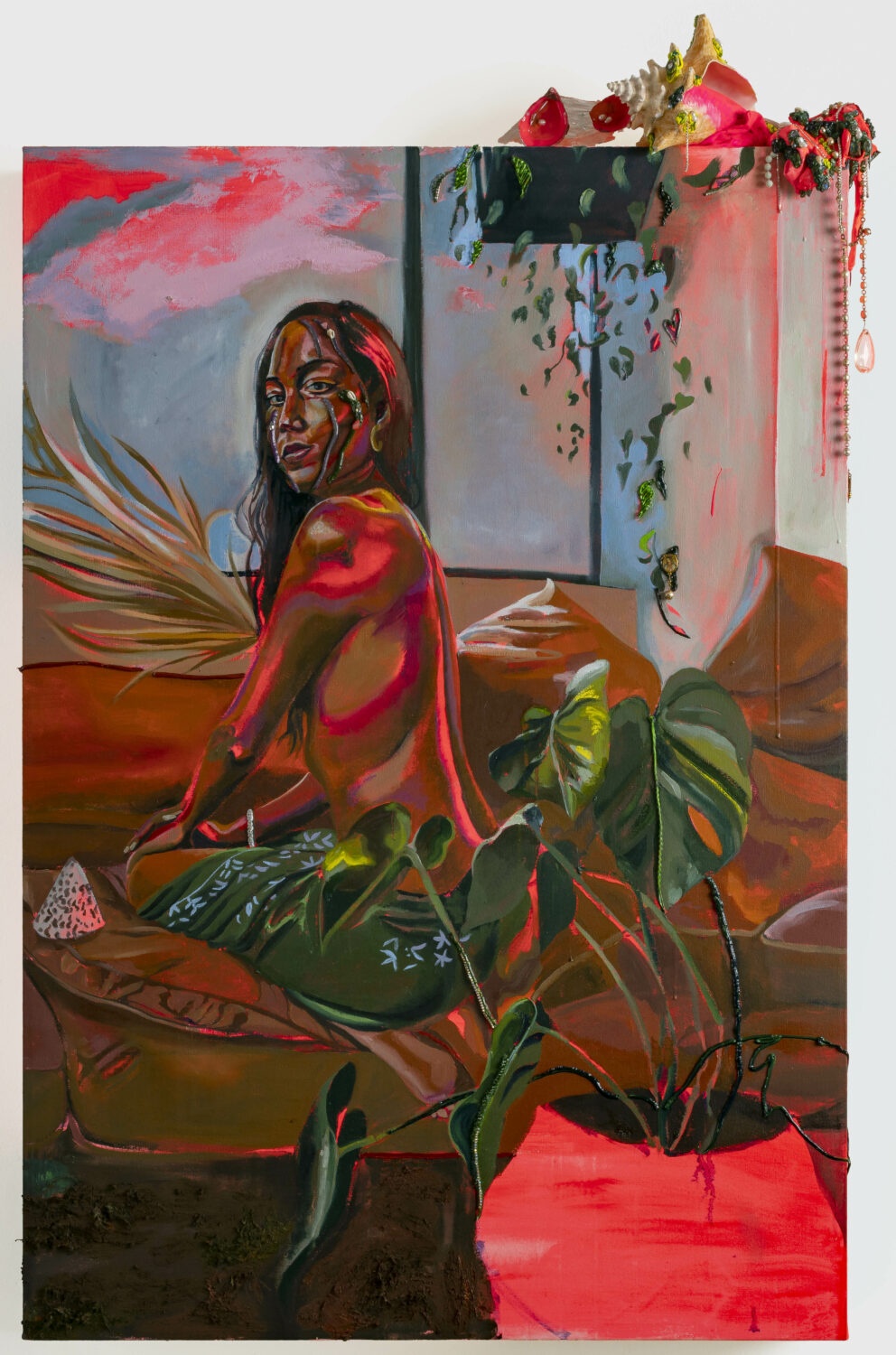

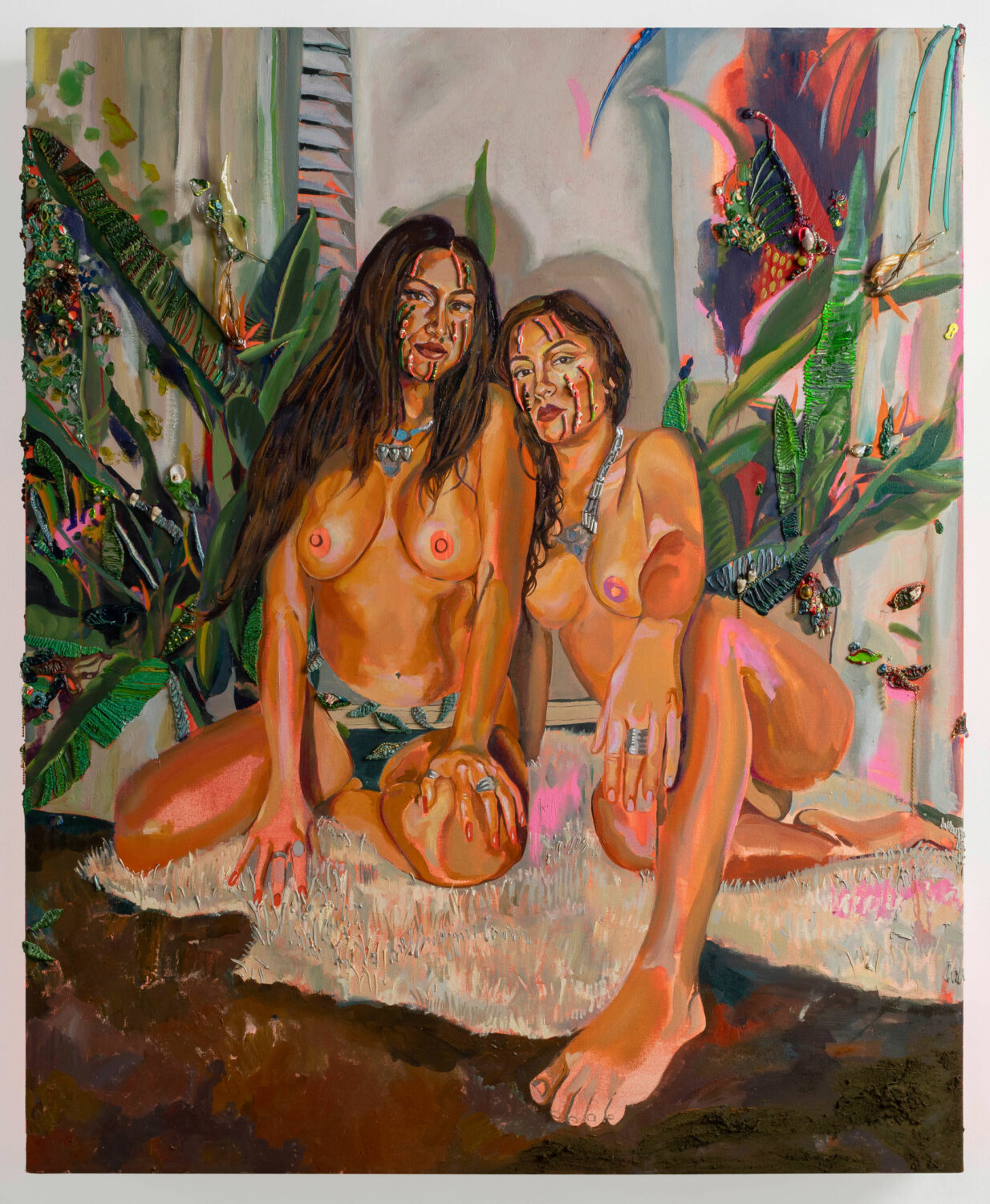

Interview: Indigenous CHamoru Artist Gisela McDaniel On The Reclamation Of Portraiture

By Something CuratedLiving and working in Detroit, Michigan, Gisela McDaniel is a diasporic, indigenous CHamoru artist. Interweaving assemblages of audio, oil painting, and motion-sensored technology, she creates pieces that “come to life” and literally “talk back” to the viewer upon being triggered by observers. In her dynamic works, she incorporates the voices of survivors of sexual trauma in order to subvert traditional power relations and to enable both individual and collective healing. Working primarily with women and non-binary people who identify as Black, Micronesian, Indigenous to Turtle Island, Asian, Latinx, and/or mixed-race, McDaniel’s work disrupts and responds to historical and contemporary patterns of silencing in fine art and popular culture. The artist is set to present a new body of work at London gallery Pilar Corrias from 27 January to 26 February 2022. To learn more about her practice and the upcoming show, Something Curated spoke with McDaniel.

Something Curated: Can you give us some insight into your background and how you first became interested in art-making?

Gisela McDaniel: I am a mixed-race CHamoru artist based in Detroit, the indigenous lands of the Anishinaabe peoples. As the daughter of a CHamoru feminist academic and former U.S. Naval Officer from a small, college town in Ohio, my existence from the start was somewhat improbable and frequently peripatetic (we moved eight times by the time I was five years old). Accordingly, my life and aesthetic have always been shaped by coming to terms with contradictions, questions of inequality, and the ability for love, dignity, and beauty to exist within, despite, and in between them.

As a small child, I was already vaguely aware that my mother and her family were racialised as non-white people in a society that glorified whiteness. I later realised they were also colonial and militarised subjects of the U.S. My Tåta (grandfather), was one of many young CHamoru men who joined the military in Guam following WWII for lack of economic and educational opportunities. My paternal grandfather’s people were coalminers from Kentucky. He worked as a steelworker. By the time I arrived at the University of Michigan to do my BFA, and then later moved to Detroit, I had a palpable sense of the politics/indignities of race and class. I was also grappling with the imperial/gendered (misogynistic) implications of Paul Gauguin’s global influence in fine art on the representation of Pacific Islanders, and particularly, young Pacific Islander women. I felt a distinct sense of offense that Gauguin, known as the father of primitivism, had appropriated a palette that “belonged” to me and to Pasifika peoples.

To answer the question in reverse order, then, art-making was something I have simply always done. It became a going concern though once my parents noticed that one of the drawings I’d done in primary school was eerily, if not actually, “good”. Funnily enough, it was a self-portrait though hardly a pretty one. It so struck them as particularly good in certain fine details, that they enrolled me in community art lessons that gave way to a specialised studio art program in a women’s high school. As a painfully shy child, and later, a reticent teen whose indigenous Pasifika culture had no safe place to exist, the influences of family and my own desire to create work that could speak to what I’ve experienced, what and who I observe and most care about, and finally, who I am as an artist, best explain my aesthetics.

SC: What is the thinking behind the selection of works included in your upcoming exhibition at Pilar Corrias?

GM: In March 2020, when the global COVID pandemic first began, I was visiting Guåhan (Guam) in the northwestern Pacific, where my mother was born and my maternal family originates from. I’d always been close to my mother’s family (who settled in San Diego) and grew up hearing about Guam and eating CHamoru food when visiting during summer vacations or on holiday. Spring of 2020 was, however, my first trip “home” and truly cemented my identity as an indigenous CHamoru and artist.

I’d arrived in the wee hours of the night and one of my aunts picked me up from the airport. She allowed me to follow her vehicle in my rental car to my hotel. Although Guam is tiny, she wanted to make sure I didn’t get lost after a nearly 17 hour flight. The next day, my Nåna’s younger cousin (a beautiful, graceful woman now in her late 60s) brought CHamoru food to my hotel. We wept and laughed together while reminiscing about my grandparents, with whom she’d remained close until they’d respectively passed a few years earlier. Being “home” and spending time with CHamoru family and peers (many of who were fellow creatives and community activists), I finally “made sense” to myself as an artist and an indigenous Pasifika woman. The level of genuine care my family had demonstrated towards me, the sensation of finally having been fully “seen” (all of which is captured in the CHamoru word “inagofli’e”, a central cultural practice) infuses every aspect of the exhibition and guided every brush stroke.

Since leaving Guam in haste (to “beat the pandemic” to get home to Detroit) in Spring 2020, I’ve been dreaming and scheming to go back. My original plan was to return for six months and do a series of paintings and interviews of famaloa’an CHamoru (Chamorro women). I was particularly interested in painting/interviewing and learning from suruhåna (traditional women healers), manåmko (elderly), and younger women and girls. During my first sojourn, I had managed to fit in a few interviews/sittings, which produced two portraits. I vowed to return as soon as possible, but for a variety of reasons that were mainly, but not exclusively linked to COVID, I haven’t been able to visit as yet. I fully intend to do so in the future.

The works I’ve created for this show nevertheless allowed me to capture the stories of a range of diasporic, famaloa’an CHamoru living in Turtle Island. About half of the women are from the northeast; the other half from Southern California; and one, my first cousin, currently resides in Utah. Although I consider all of them, broadly speaking, to be my “primas” (cousins), only three are related by blood, specifically through my Nåna’s “Capili” Clan (note: clan or “familia” names are important ways of delineating relationships in CHamoru culture). Since the majority of CHamoru people currently reside in the U.S. “mainland” – displaced by militarised colonisation following WWII and, more recently, what some refer to as climate colonialism – documenting our stories in the diaspora also has a certain urgency.

As a painter whose presence in the U.S. is a product of the same historical and political forces, and whose shared mahålang (yearning) for my Pasifika “home” and culture are equally deep, bringing this show to fruition is a watershed moment. It not only allows me – and my primas – to speak back to the primitivist legacy of Gauguin that has unavoidably shaped my aesthetic/how we have been historically represented, but to highlight the ways in which the colonial grip and intensifying militarisation of a Pasifika peoples has profound consequences for and is actively resisted by 21st century diasporic, CHamoru women. I also understand and offer this assemblage of works in homage to ancient CHamoru cosmology which holds that the Sister-Brother duo of Fu’una and Puntan co-created the world, starting with Guam. As descendants of the matrilineal society which CHamoru historians suggest is reflective of this cosmology, one in which women have always wielded considerable respect, Manhaga Fu’una (Fu’una’s Daughters) presents complex stories of contemporary, diasporic CHamoru women who continue to fashion and engage the world they confront with wit, courage, strength and not infrequently, unavoidable sorrow.

A final aspect of the exhibition that I should also point out is the serendipitous presence of the single non-CHamoru subject depicted in “Måmes” (Sweet/ness). Last summer, while at the Art Omi Residency in upstate New York, I crossed paths with a fellow artist and Pasifika Elder, si Tun Dan Taulapapa McMullin. I was deeply honoured when he asked if he could sit for me and we spent a wonderful, playfully subversive afternoon together talking story about Pasifika culture, the meaning of art, colonialism, resistance and more. As a respected scholar, poet and queer Samoan artist, I am deeply grateful for his contribution to the exhibition as a subject and for the work he has done more broadly for Pasifika communities worldwide.

SC: Could you expand on the figures you depict — what influences their forms and the contexts you place them in?

GM: I should make a distinction between the figures and the objects or artefacts that are embedded with them in a given portrait. I should further specify, that a key aspect of my practice is ensuring that the subjects – or figures in this case – are first invited to collaborate with me on every aspect of the process and have a tremendous amount of input, if not control, in how, with what objects, and under what circumstances they will sit for a portrait, normally preceded by a conversation/interview.

Given the long and on-going history of colonisation which the CHamoru people have and are still enduring* it’s critical that the famaloa’an CHamoru (Chamorro women) depicted played active roles in choosing how they would be posed, in some cases, with whom, and with which objects. It’s also significant that the objects they selected, some of which were then embedded directly into their portrait, were given voluntarily. Museums across the globe continue to grapple with what indigenous peoples view as acts of theft and desecration. Inviting the subjects/figures to make these determinations themselves radically transforms both the meanings and interactions between the subjects, myself as an artist, and ultimately, the viewers.

That said, I would suggest that embedded and depicted objects operate like hints at the inner life of the subjects and the outer life of the material journey of those items in the context of militarisation, global capital, diaspora and both whispers and shouts of imperialism. The appearance of fences in various pieces speak to the themes of imposed constraint, land seizures, even contamination of natural resources although accompanying audio pieces detail the often fierce but always persistent agency of each subject/figure as counterpoint.

*Please see: “‘USA has not supported self-determination for the Chamorro people of Guam’ say UN Experts”

SC: What interests you in working with motion-sensored technology?

GM: The ability to establish a kind of physico-auditory boundary around and in conversation with the subject of the portrait, as well as the objects embedded in the portraits which are imbued with personal meaning. There’s a way in which the introduction and pairing of audio with portraiture humanises both the subjects and the encounters of the audience with the paintings. The motion-sensor implicitly challenges the almost inevitable objectification and otherwise unfettered voyeuristic consumption of the pieces and more importantly, the subjects which they depict. As an indigenous Pasifika painter and woman, it’s especially vital that I insist on not just questioning but interrupting this practice which has classical, extractive and profoundly imperial roots. What is offered instead, is an opportunity to approximate the experience of “talking story” which is a central and communal practice in indigenous Pasifika culture.

SC: What are you currently reading?

GM: Evelyn Flores Flores and Emelihter Kihleng, Indigenous Literatures from Micronesia;bell hooks, The Will to Change; Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass; andDaniel Immerwahr, How to Hide an Empire.

Gisela McDaniel: Manhaga Fu’una at Pilar Corrias Savile Row run from 27 January to 26 February 2022.

Feature image: Gisela McDaniel, Prima, Nieta, Nåna: Pasifika Bailadora [Detail], 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Pilar Corrias, London