The Continued Revival of Skate and Street Aesthetic

By Something Curated

As the growing ennui of open-face catwalk couture continues to mount, so too does skate and street style’s return in all the bases of 21st century fashion. From the runway to the subway to the skate park, the camo-clad hoodies of Supreme’s red-and-white square, Gosha’s russian scrawls, and the ever-changing, now you see it, now you don’t logo of Vetements – sometimes behaving more like an inside joke than a proper branding identity, appear on all sorts of styles, most often in the company of an unending, uncategorizable roster of other designers. The division between skate and streetwear is also rapidly devolving, as new-age streetwear is less political than its original call-to-arms: with its focus on challenging the fashion industry through subverting established aesthetics rather than challenging governmental and social regimes (more on the aesthetics and politics of new-age street fashion here).

Collaborations are a fundamental part of skatewear’s concept of existing alongside everyday life and its happenings, versus being the centre of attention as a singular “brand” or anchoring itself to a particular moment in fashion culture. Skatewear’s genius is its pliability and its ease, both materially and as an aesthetic. It bends and adjusts to emerging trends as they come and go, letting movements in fashion and labels-of-the-hour flow through the movement and exert their influence through collaborations. But at the heart of the streetwear movement is its resistance against the permanent influence of single label.

By doing this, skatewear has been able to stay relevant since Stussy in the mid 80s. Its chameleon-like adaptability is also why skatewear is having its second coming, with the Vetements (founded 2014 by Georgian Demna Gvasalia) led revolt against “fast fashion.” In fact, because both skate and streetwear do not owe an alliance to any particular brand, they can take reference and inspiration from current events in both world news and (pop) culture. But this is not without its own batch of criticism – read our thought piece, alongside those of London’s leading streetwear designers, on the stakes of irony and appropriation in new-age streetwear here.

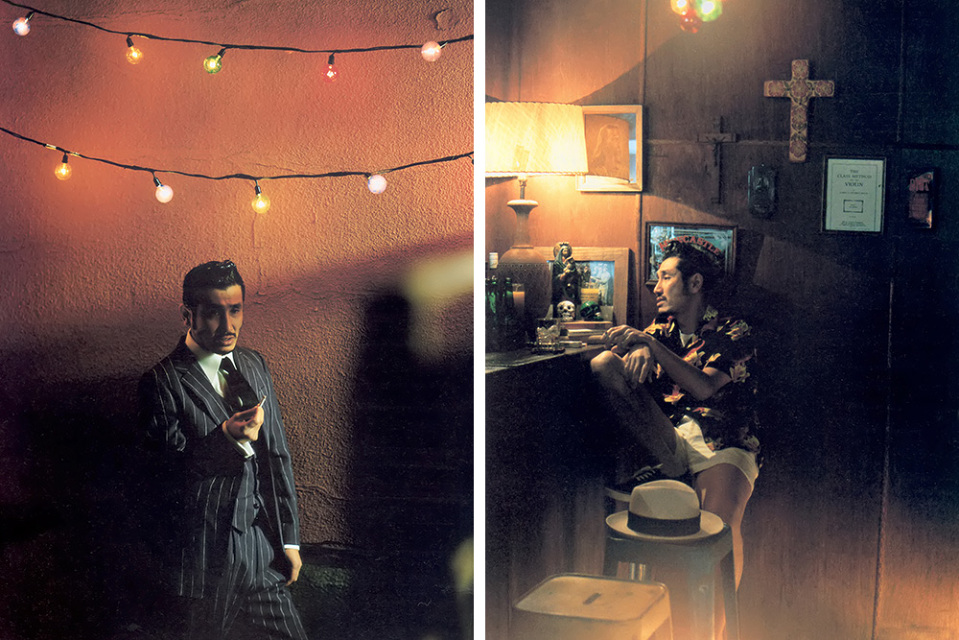

Take, for instance, the relatively unheard of Japanese brand Wacko Maria, established in 2005 by two retired soccer players, Nobuhiro Mori and Keiji Ishizuka. While most known for its embroidered satin bomber jackets and Virgin Mary screen printed hoodies, Wacko Maria has also done collaborations with American director Jim Jarmusch (S/S 2015) to produce a capsule collection around his cult vampire film Only Lovers Left Alive. Six years prior, for their S/S 2009 collection called‘Jamaican in Brixton — Pictures of Smoke,’ Wacko Maria honed in on the historical reference of Brixton’s Jamaican heritage stemming back from the 1940s and 50s.

Because they move through the fashion industry through collaborations, streetwear brands are illusory in the sense that they’re impossible to pin down or stabilize to a singular style or name. They exist purely as a “limited edition” batch while flittering from one collaboration to the next. Like Vetements, streetwear is both anonymous and iconic. It’s anti-fashion and at the frontier of the fashion world at the same time. Streetwear is all about the fantasy it conjures up as by definition it’s always changing form, perhaps more alive than “lifestyle” brands themselves. Streetwear is essentially a bespoke garment that is always measured up as a perfect fit for the culture of today.

Finally, streetwear makes itself principally about people. By reflecting the trends of the day in a way that is nonconformist and anti-establishment, it reflects the discerning personality of the wearer and propels him or her forward into the frontier of fashion while making it look effortless. The wearer appears to stand for the anti-luxury, the anti-establishment, and the anti-trend. The anti-fashion aesthetic is the new fashion; Streetwear has run with that module from its beginning in the mid-80s. Now that high fashion is moving in that direction, plus with the general sharing and melding of these (sub)cultures across the world thanks to the internet (e.g. Gosha meets Supreme meets Palace meets A Bathing Ape conjures Dover Street Market), streetwear is having its second coming.