The Mansard Gallery: Blurring The Lines Between Art, Design & Retail A Century Ago

By Something CuratedFor over two centuries Heal’s has been a destination for contemporary design. What is less known is that for a brief period in the early 20th century the business was also home to a pioneering gallery space that played a key role in the history and development of modernist art in Britain. To mark the centenary of the Mansard Gallery opening at the Heal’s building on Tottenham Court Road, Something Curated traces the story behind some of the seminal exhibitions and entities to have graced the gallery.

Starting life as a feather filled mattress maker, then a novelty to those Victorian’s more accustomed to straw beds, Heal’s has remained at its current location on Tottenham Court Road since 1840 where it became the centre of design and retail innovation in Britain. This was thanks in no small part to Sir Ambrose Heal. The great grandson of the businesses founder, John Harris Heal, Ambrose joined the family firm as a furniture designer in 1983. Inspired by the Arts & Crafts movement, his catalogues of furniture proved an instant hit with London’s middle classes and alongside his innovative approach to marketing (it was he who introduced their distinctive ‘At the sign of the Four Poster’ logo) made him the natural successor as chairman from 1913 until 1953.

What is remarkable about Sir Ambrose Heal is the way in which his passion for art, design and retail were not exclusive of one another but often overlapped. This was certainly the case with the Mansard Gallery, which he launched on the fourth floor of the Heal’s building in 1917. In an age where “experience” is sometimes valued more highly than the product itself, turning a retail showroom into an exhibition space is hardly remarkable. Yet, in Edwardian Britain such a move was unheard of and could have easily failed were it not for the fact Ambrose was as much a part of the artistic circles he wished to showcase. Commenting on the influence of the Slade School of Fine Art, located around the corner from Heal’s on Gower Street, Professor John Aitken has said: “He had numerous friends at the Slade and met his second wife, Edith Todhunter there at the end of the 19th century. It is therefore no surprise that Ambrose should set up a gallery at Heal’s to showcase the best and, in many cases, most innovative art.”

The first show held at the Mansard Gallery was, however, not an exhibition of radical painting and sculpture as one might expect. Instead, Ambrose sought to elevate the work of the commercial artist by displaying posters produced for the London Underground within a formal gallery setting. Entitled ‘Poster Pictures’, the show was curated by close friend, and managing director of the London Underground, Frank Pick with whom Ambrose had founded the Design and Industries Association (DIA) in 1915 to better promote links between design, manufacturing and retail.

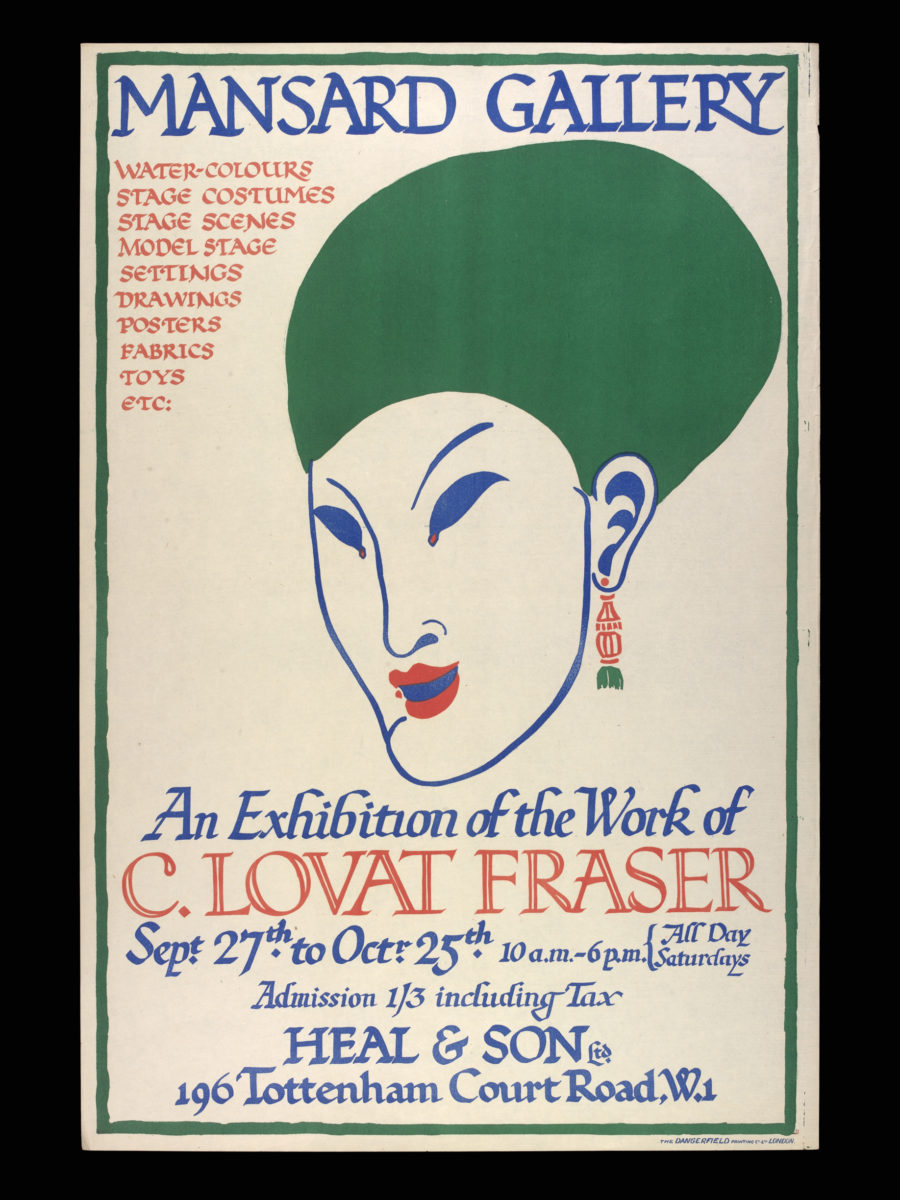

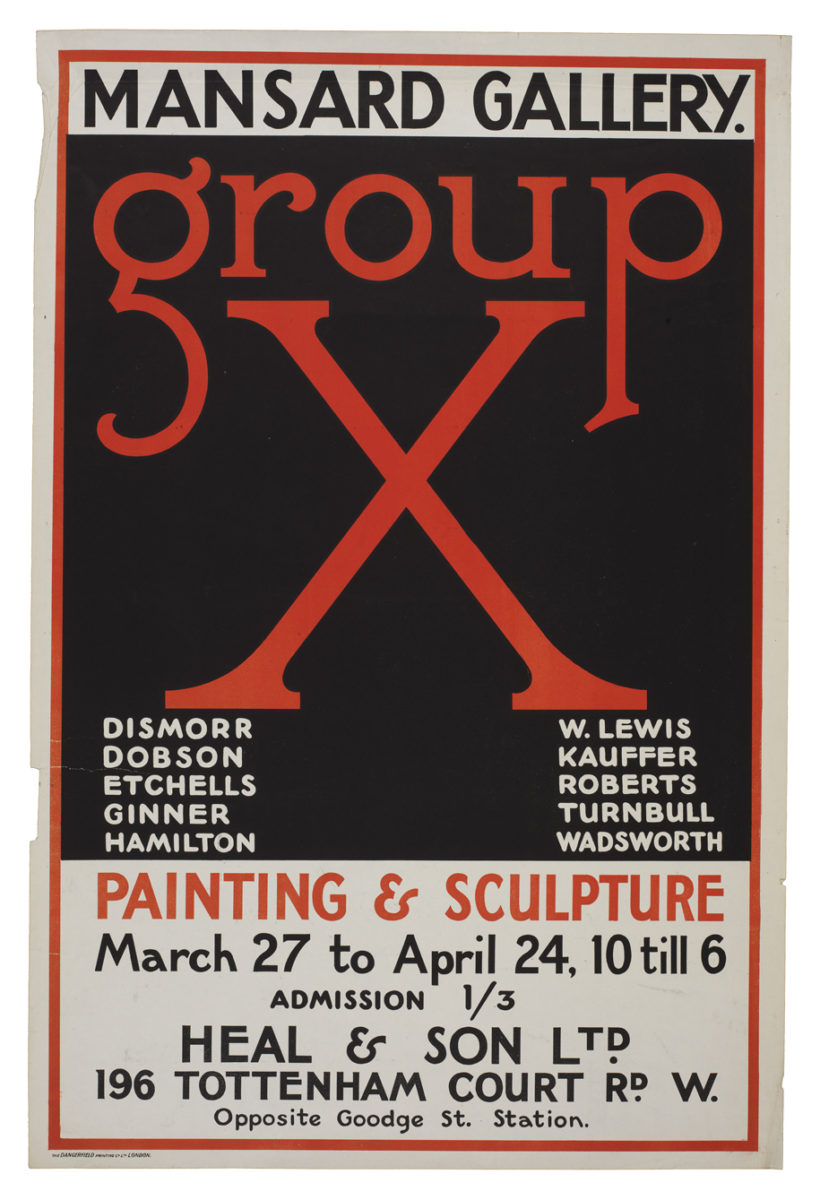

The exhibition happened to feature the work of influential designer Edward Mcknight Kauffer who that same year would go on to design another poster for the Mansard Gallery, this time to advertise a collective show by The London Group. One of the oldest artist led societies in the world, the group was founded in 1913 to provide those shunned by the conservative Royal Academy a chance to exhibit their work. And this they did, with a number of shows at Heal’s throughout the 1920s which included work from Walter Sickert, Jacob Epstein and Ethel Sands to name a few. One of the founding members of the London Group, Wyndham Lewis was another recurring figure at the Mansard Gallery where in 1920 he attempted to revive the Vorticist movement (a form of British modernism that had flourished before the war) with the ‘Group X’ show featuring amongst others William Roberts, Cuthbert Hamilton and, once again, Kauffer.

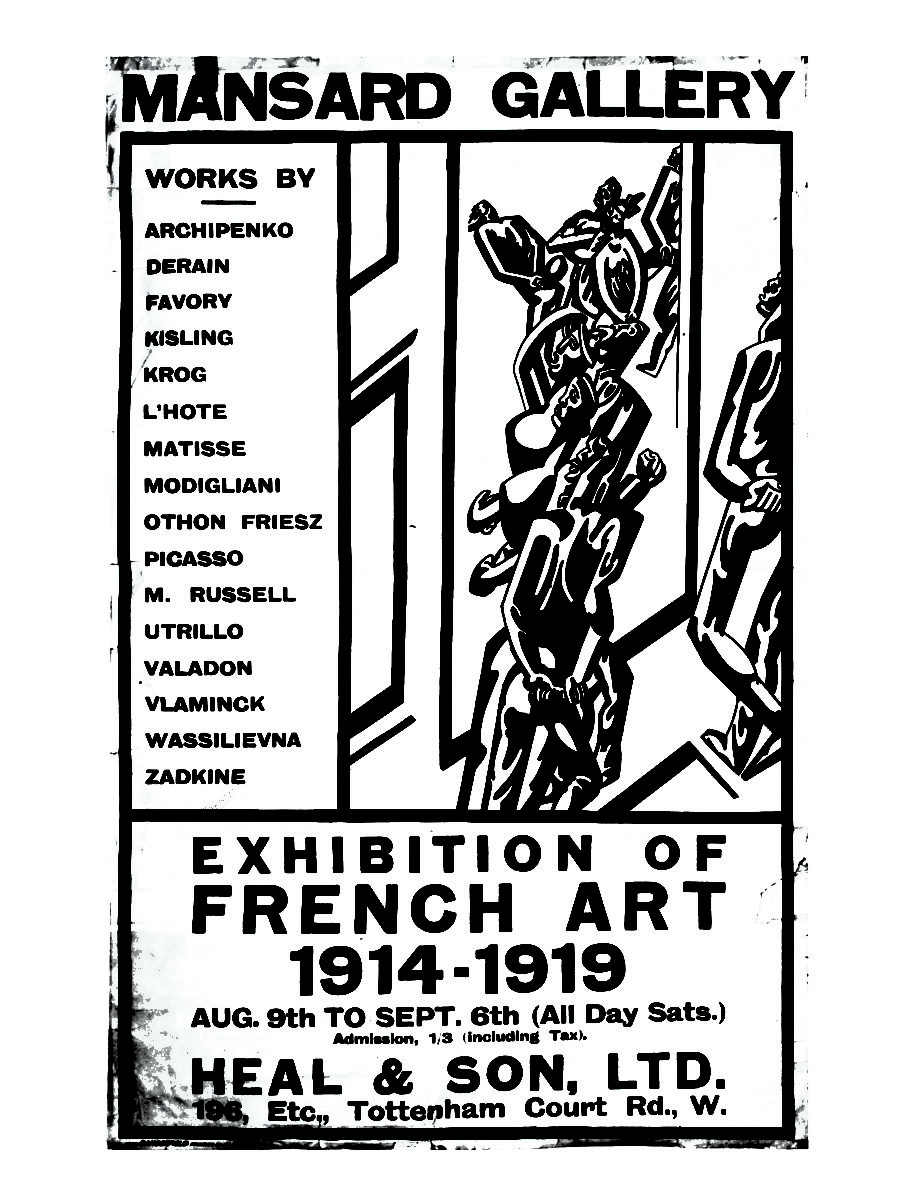

Unfortunately for Lewis, the Mansard Gallery’s watershed moment had already passed a year earlier with the opening of a seminal showcase of contemporary French art. Curated by writer and poet Sacheverell Sitwell, the ‘Exhibition of French Art 1914-1919’ brought together works by Picasso, Matisse and Modigliani whose painting ‘Le Petit Paysan’ (‘The Little Peasant’, 1919) was the artist’s first to be exhibited in the UK. In an essay simply titled ‘Modern French Art at the Mansard Gallery’, artist and critic Roger Fry wrote of his joy upon seeing the show: ‘what an extraordinary variety of presentments, what innumerable different visions, one can enjoy in this gallery!’ Not all were convinced by such novel pieces from across the channel with a reviewer from the Times simply labelling the show “ghastly”.

With such innovative work on display, the Mansard Gallery quickly established itself as one of the meeting places for London’s, if not Britain’s, avant garde scene. One such group that frequently made the trip up to the fourth floor of the Heal’s building during this period was the infamous Bloomsbury Group, whose designated furniture maker the Omega Workshops was situated a few minutes away in Fitzroy Square. Painter Vanessa Bell’s The Friday Group regularly put on shows at the Mansard Gallery with Virginia Woolf writing in her diary that it was there she met Aldous Huxley for the first time at ‘An Exhibition of Works Representative of the New Movement in Art’ curated by core member Roger Fry.

The Mansard Gallery continued to flourish as a commercial and artistic space right up until the 1970s. However, it is this early period that spanned from its opening in 1917 through to the “roaring” 1920s for which it will increasingly be remembered. Information and documents relating to the exhibitions that took place there are scarce with the distinctive posters designed to advertise these shows often acting as the most reliable evidence for what took place. One thing that is certain is that the important role the gallery played in British art during this time deserves to be more widely acknowledged and celebrated.

Words by Dale Marshall | Images courtesy of Heal’s