Do You Know the Artist Donald Rodney? Here’s Why You Should

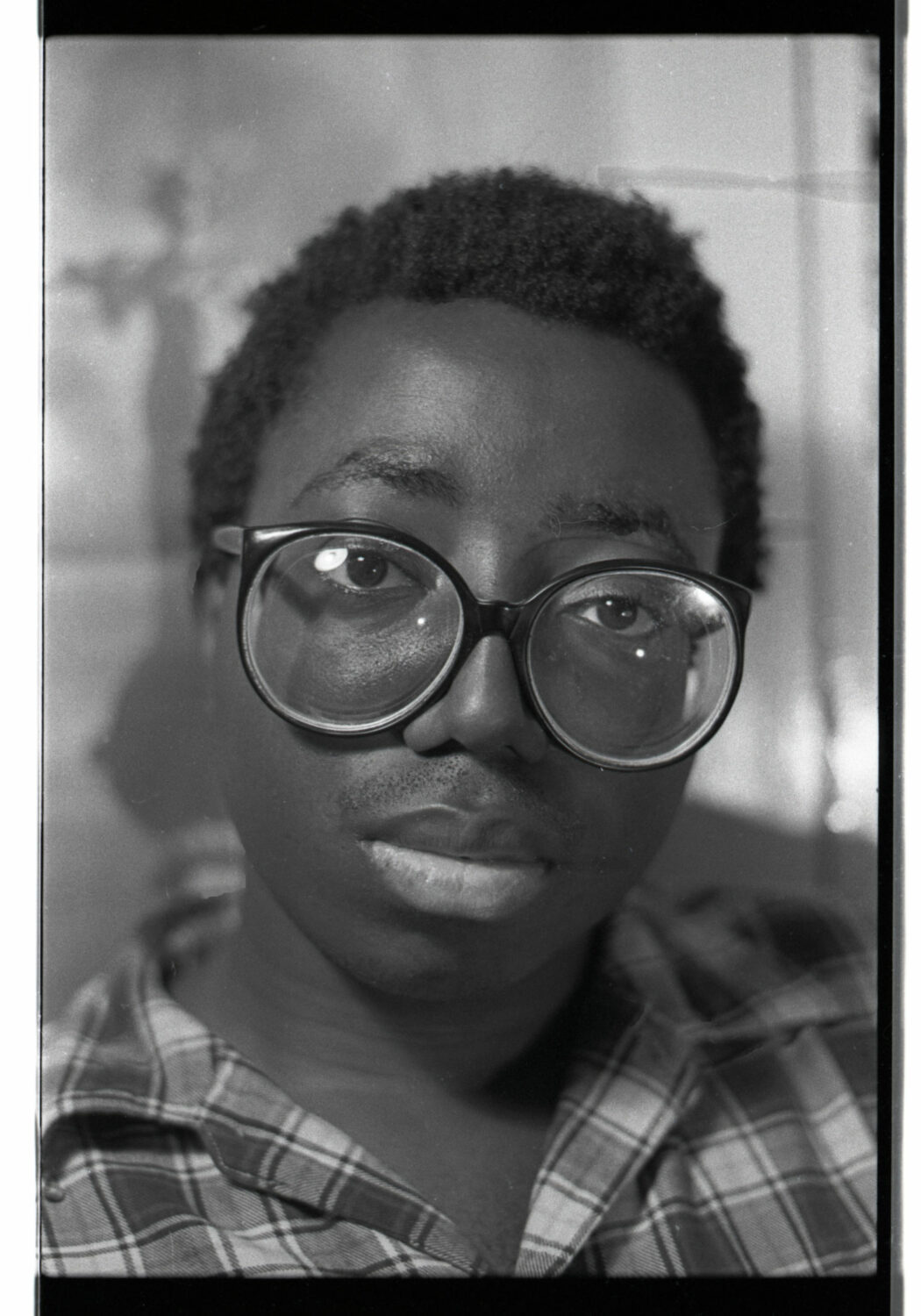

By Nicole Yip and Robert LeckieOpen now and running until 8 September 2024, Spike Island presents a major survey exhibition of the late British artist Donald Rodney. Rodney worked across sculpture, installation, drawing, painting, and digital media, experimenting with new materials and technologies throughout his life. A co-founding member of the BLK Art Group — an association of young Black artists formed in Wolverhampton — Rodney was born to Jamaican parents, and grew up in Smethwick, on the outskirts of Birmingham.

His work is known for being incisive, acerbic, and evocative in its analysis of the prejudices and injustices surrounding racial identity, Black masculinity, chronic illness, and Britain’s colonial past. The new show, Visceral Canker, seeks to introduce a new generation to Rodney’s life and work, cementing his place as a vital figure in British art.

On the occasion of Spike Island’s presentation, Spike Island Director Nicole Yip, and co-curator Robert Leckie, Director of Gasworks, share their thoughts on the pioneering artist and the thinking behind Visceral Canker.

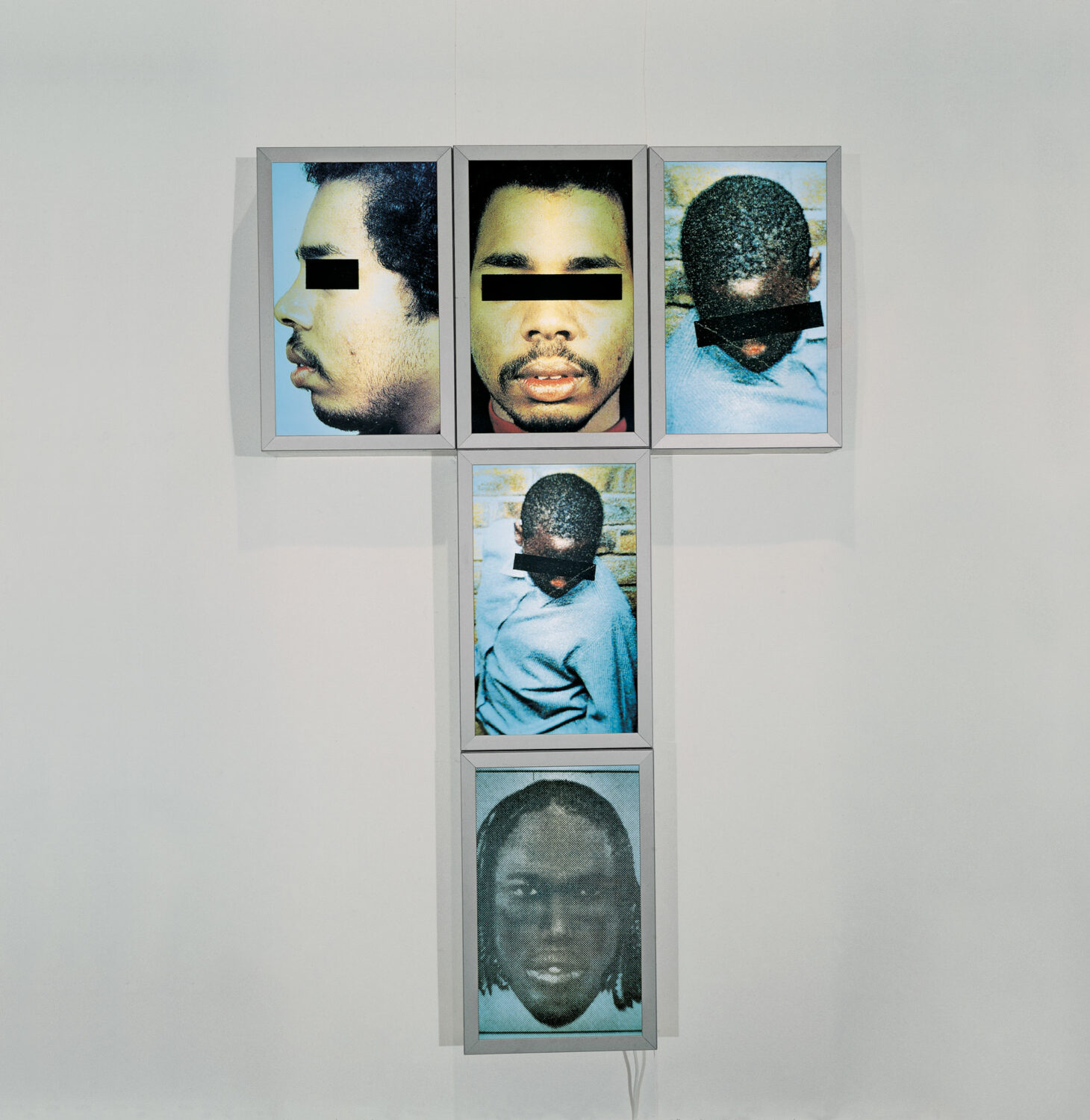

It is important to continue looking at and thinking about Donald Rodney’s work today because he was an exceptional artist making poignant and experimental work throughout his life about social and political issues that still persist. There are echoes of his lightbox work about the media representation of Black sportsmen, John Barnes (1991), for example, in the racism experienced by the Black football players that missed penalties while representing England at the Euro 2020 final.

And Donald was clearly ahead of his time when it comes to making and thinking about art in relation to his experiences of illness, disability and hospitalisation, as evidenced by both the subject and construction of his large-scale x-ray works, such as Britannia Hospital 3 (1988).

We are interested in many aspects of Donald’s work, from his carnivorous engagement with different materials and technologies, to his exploration of the ills, or ‘canker’, at the heart of society. It’s fascinating, for example, to reflect on the intellectual and technological ambition of works such as Psalms (1997) and Autoicon (1997-2000), which were both conceived in the late 90s, and which both function as haunting, if partial, archives of Donald himself.

Donald first came into contact with the BLK Art Group during his time as a student at Trent Polytechnic in Nottingham in the early 1980s. This informal circle of young Black artists of Afro-Caribbean descent was instrumental in the development of what eventually came to be known as the Black British Arts Movement.

It was through his friendship with fellow artist Keith Piper, who was in the year above him at Trent, that Donald got to know other key members of the group like Eddie Chambers. Together they organised several conventions to debate the possible meanings and implications of ‘Black Art’ and staged a series of exhibitions across the Midlands under the rubric of ‘The Pan-Afrikan Connection’.

The curatorial premise of the exhibition has always been about bringing together as much of Rodney’s surviving work as possible, and to present this to a new generation of audiences. The last in-depth survey of Rodney’s work took place over 15 years ago, which means that although his work continues to be hugely influential, there is an entire generation – ourselves included – who have never had the opportunity to experience his work firsthand in any comprehensive way.

In putting together this presentation, we were also aware that there has been a tendency to allow certain markers of identity to over-determine how Rodney’s work is understood and contextualised. As such, we were keen for our presentation to instead allow for multiple and open-ended readings of the work, so that viewers can draw their own connections and conclusions.

Fundamentally, we hope that Donald’s work becomes more widely known and appreciated through this exhibition, and that his reputation becomes cemented as a vital figure in British art history. We hope that visitors will be as moved and inspired by the work as we have been.

Feature image: Donald Rodney, The House that Jack Built, 1987. Installation view at Spike Island, Bristol. Work courtesy Sheffield Museums and The Donald Rodney Estate. Photo by Lisa Whiting