At Home Nowhere: Ian Mckell on Nomads, Revolution and Belonging

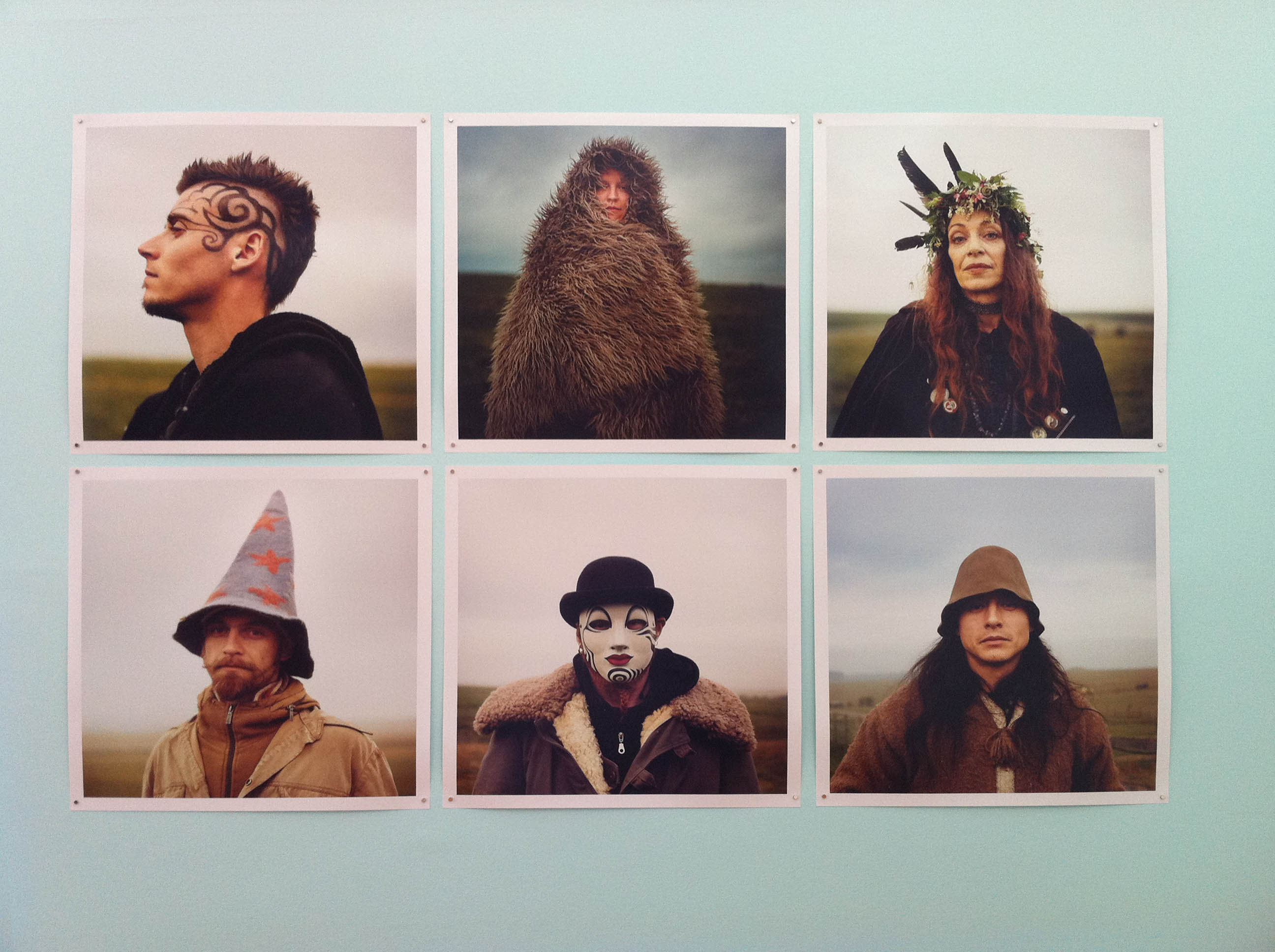

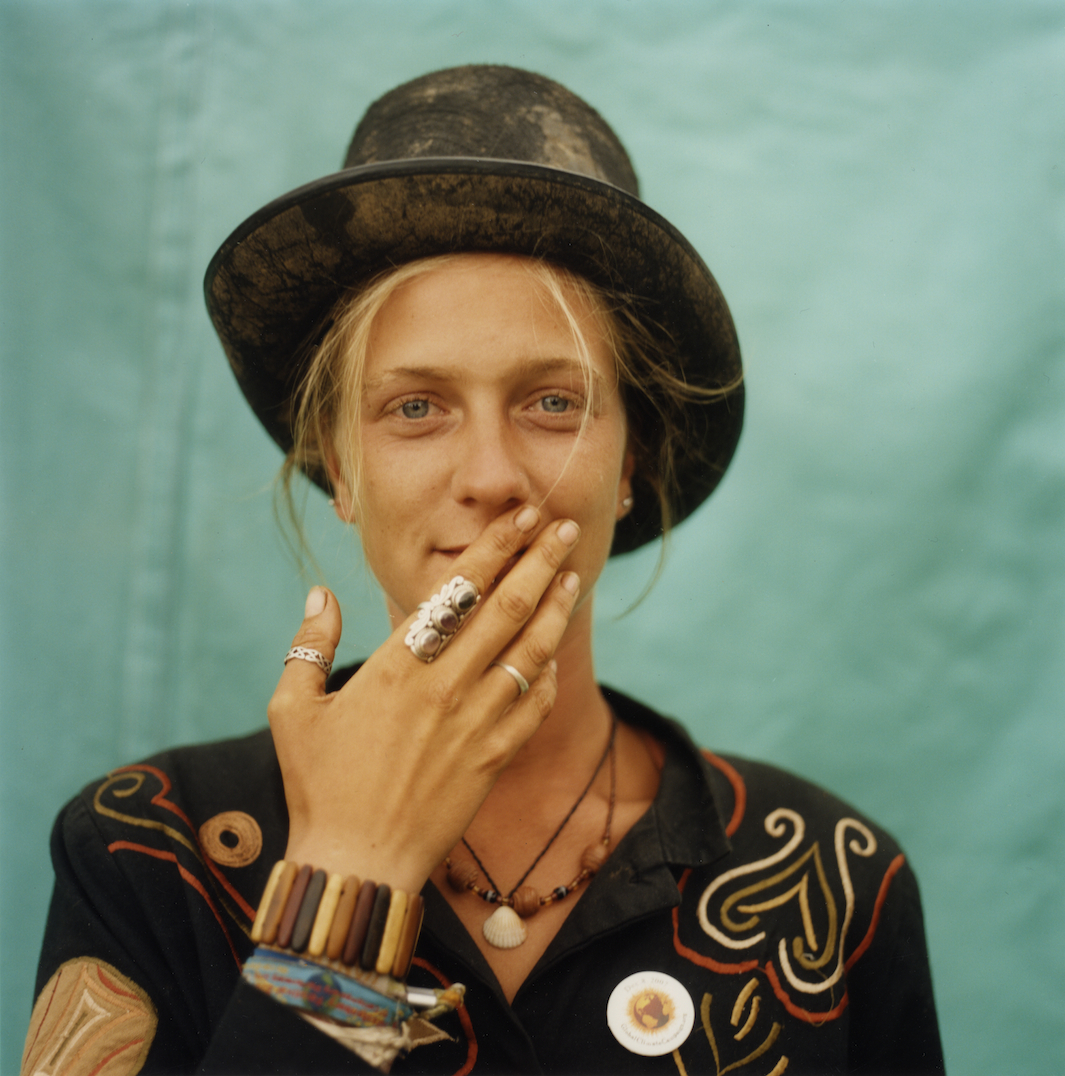

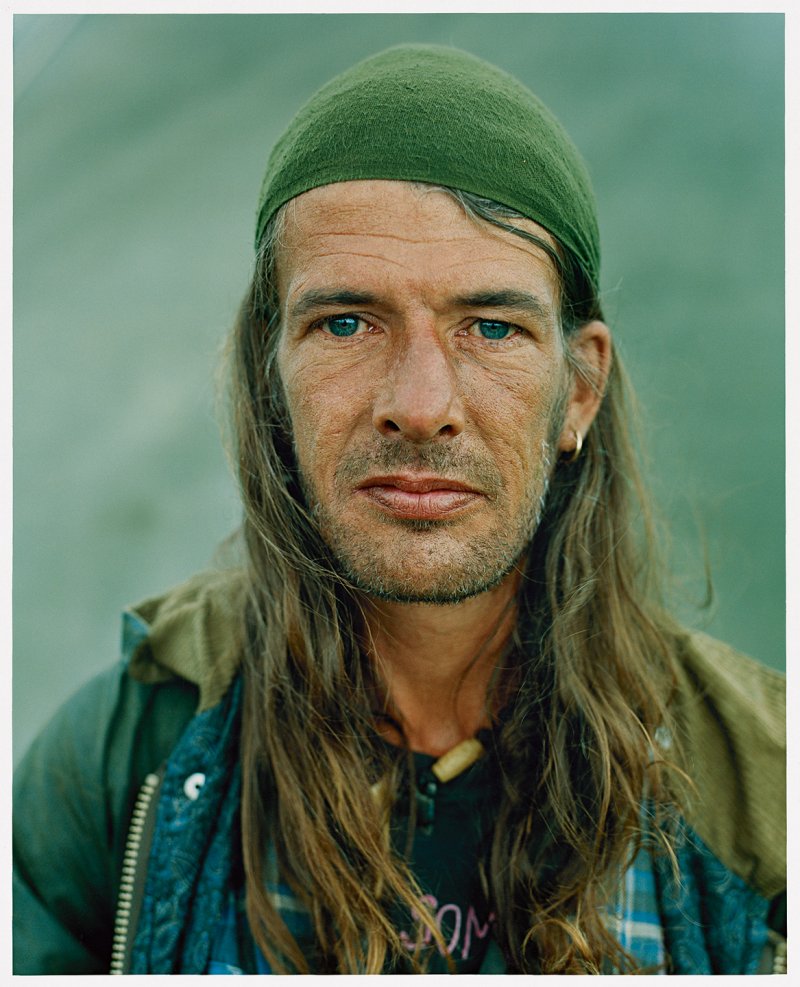

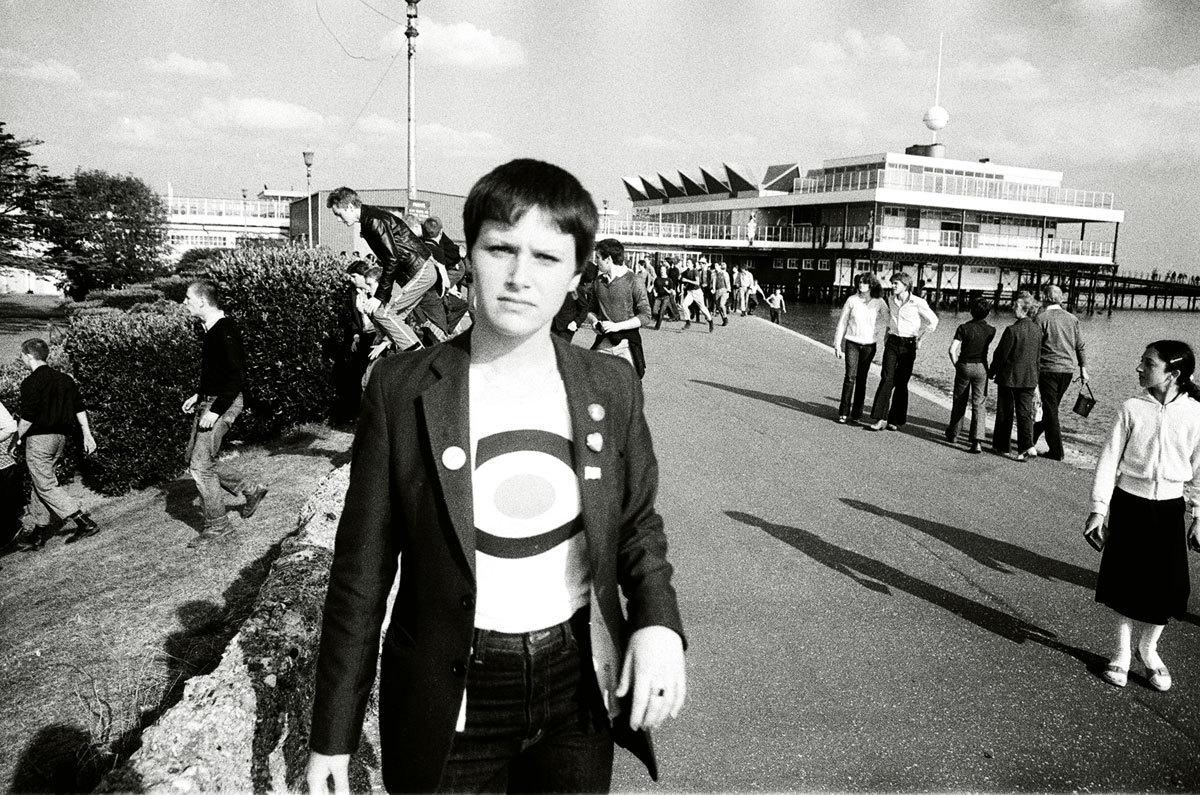

By Something CuratedIain Mckell (b. 1957, Dorset, UK) is a photographer of people and cultures who lives and works in London. Known for his immersive shoot with Kate Moss, where he and the model travelled and lived with the UK’s new-age gypsies to produce a photo series for V Magazine in 2009, McKell has produced a rich oeuvre that artfully and truthfully captures the lives of nonconformists from the country to the city. McKell is a unique force in the world of portrait photography in that he avoids romanticizing the often-misunderstood or misrepresented lifestyles of the subcultures he chooses to represent. His keen eye for understanding social customs and taboos extend far beyond the lens, stemming from an intrinsic fascination with people and society, convention and its discontents, as well as a flexible disposition and patience that grants him access to the secret worlds his images convey. Here, Something Curated speaks to McKell about his approaches to society and photography and his experiences living and working in London, to get a glimpse behind the lens of one of the most contemplative and poetic social photographers living and working in London.

Something Curated (SC): What was it like growing up for you on the coast? How did it influence your practice as a photographer and your interest in nature, culture, and subcultures?

Iain McKell (IM): I’ve been revisiting it these last couple of years. I have been doing generic seaside towns -Whitney Bay and Great Yarmouth – they’re all similar in a way, they’re all seaside towns that i have an understanding for. But recently I started thinking that it doesn’t have to be the seaside, it could be Birmingham Town Centre; Anywhere that has human beings living and maybe predominantly the working class – those are people I’m drawn to. Why is that aesthetic to me appealing? I don’t know — I would need to lie on a psychologist’s couch for hours to figure that out — the more money people have the more boring they are?

SC: That’s interesting how growing up on the coast has allowed you to realize that you don’t need it as a standalone subject, that it’s more about people than places for you, in a way. You mentioned your interest in the working class – how does that compare to your early foray into fashion photography?

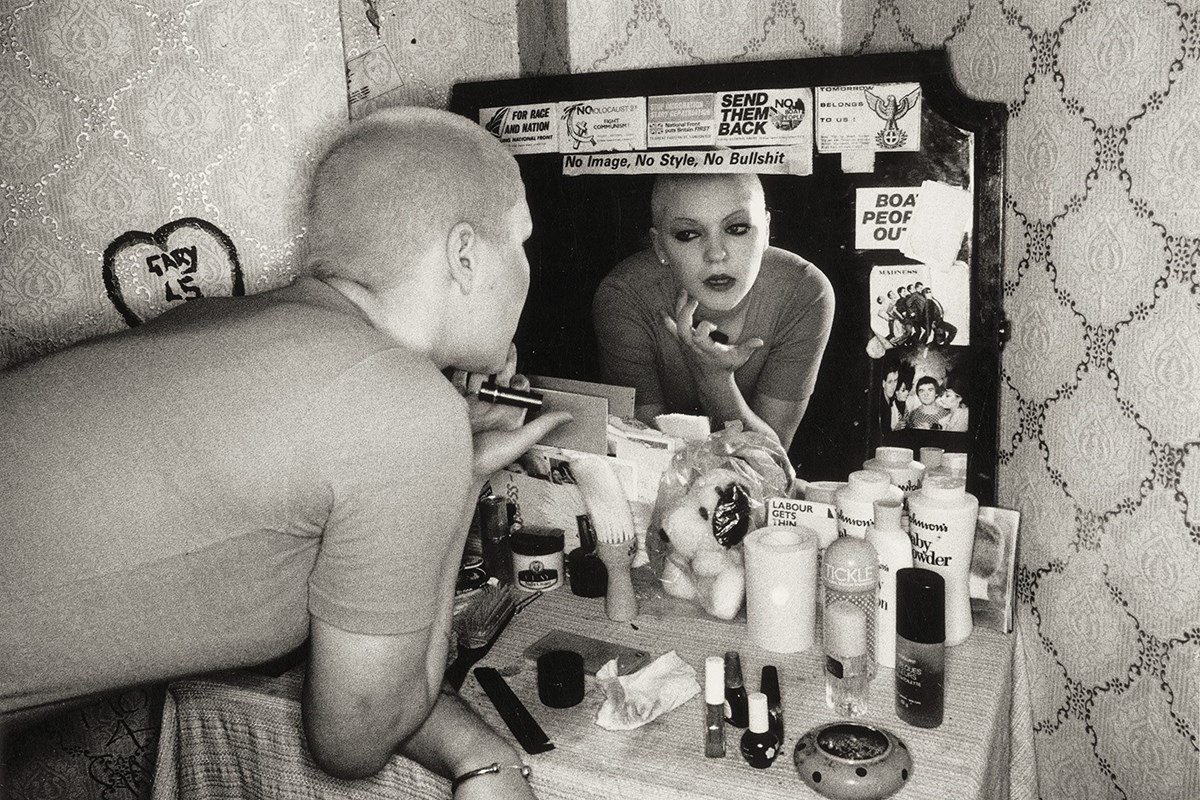

IM: It kind of just happened, I didn’t go out looking for it. I did a documentary series of pictures called “The Cult with No Name” in the 1980s – the media called it the New Romantics. I stumbled across this club in London and it was a David Bowie club – I was into Bowie, there were people like Boy George and that underground flamboyant art student energy going on – the underground energy of London. These were the individuals that were going to go on and shape things. And one thing led to another and I ended up photographing Madonna, she was in the New York club scene as well. It was all part of this club culture that was about people coming together and interacting and having like minds — Madonna was on the parallel universe of it, New York.

SC: What do you mean by that – the parallel universe of New York?

IM: New York is like the parallel universe to London. What’s interesting about New York is the social boundaries. People go out all day and night and they kind of keep to their own bubbles and circles, which I don’t do. I transcend all bubbles. I never saw myself as an inmate to that flamboyant culture because I didn’t wear makeup and wasn’t externally expressing that. But maybe internally I was identifying with the wild side. Madonna was in this parallel universe. I’ve been to NYC lots of times and they would always say that I reminded them of someone in London – it’s two parallel cities and neither really know the other exist!

SC: For street photography, how do London and New York compare in your book as subject material?

IM: I haven’t been to NYC in a couple of summers, but I’ve noticed you’ve got girls in Brooklyn with tattoos and you get that in London as well, there’s more of that in NYC than London – but I suppose they are hipsters, and we’ve definitely got that in Shoreditch.

SC: Shoreditch reminds me a lot of Williamsburg… it’s true, there are so many overlaps… haha! But I love what you’re saying about transgressing these social boundaries – your photography feels very dreamlike, where you are transcending this bridge or divide in society that urban culture creates — maybe boundaries become less strong through travel, like on the Greyhound bus or train. Haven’t you done a lot of portraits on public transit?

I: I don’t commute, but when i’m traveling around London and using the underground, I always make a point of talking to who I’m sitting next to. Almost without fail I’ll do it. I do it for 3 reasons: I like talking to people, its that simple, and I like taboos –I mean, starting a conversation with a stranger is not offensive or illegal or immoral but it’s still kind of taboo, and thirdly, because it makes the journey go by really quick. Sitting on the central line from Stratford to Notting hill Gate — why waste it? I kind of enjoy it, and 9/10 are really receptive. And then one isn’t and you feel a bit awkward, haha!

SC: Let’s talk a little bit about your photo book project The New Gypsies (2011). You were living with and photographing this tribe off and on for over a decade. I read in your interview with AnOther Magazine that the gypsies had wifi and other modern-day technologies, and how much it contrasts the idea of gypsies being so removed from the present. Did it ever feel weird having all this high-tech photo equipment whilst travelling around with gypsies?

IS: Not really! The places you travel through transport you into another dimension – but I was fully aware that I was visiting people living with horses and wagons yet I’m driving a car to get there. My cameras are part of this otherworldly persona – I am from the 21st century. I always knew that I was an outsider to these gypsies. I got a lot of respect from the travellers because I was prepared to live, walk, and eat with them – I was prepared to live like them, not just with them.

SC: How does your immersion in the life of subcultures influence how you see, interact with and shoot subjects in the city of London?

IS: I live in East London – in Forest Gate, it’s way East near Essex. It’s all really gentrified now. There’s a local deli and all the white middle class people in Forest Gate go there. You go into the deli and they have that urban brick look – open coal burning pizza at the back and it’s all middle class, and outside it’s completely different, the streets are predominantly African or Indian. And the pub across the street is all gentrified and bohemian looking and everyone inside looks so high class and they’re in forest gate but kind of invisible. I have certain days where I feel energized to take pictures, and I walk past the deli and I see a mom and child and dad and he looks the middle class part, and I took a picture through the window and sometimes you get away with it and sometimes you don’t.

SC: [laughs] And this time you didn’t?

IS: Well, it was a digital camera, so of course you the image you took, and then it dissappears back to what the camera is pointed at and through the camera I saw the guy looking at me with an expression of like “What the f***?” so then I spun around, pretend there’s a problem with my camera, fiddle with it — it’s not like a writer where you can go away and write about it, you need the physical act of the camera. Then I walked up to them and explained that I’m a local and I do street portraits and I’m coming from a good place really in my head and I said, “Do you mind if I take another picture and this guy goes “Yes I do mind.” [laughs]

It went just like that. And the whole thing was just so awkward – you know, when you feel really embarrassed, like, I’ve done something worse than talking to someone on the underground and I just wanted the ground to swallow me whole.

And the woman was just this sort of passive one with the baby, smiling – a middle class smile. I said I’m really sorry, are you locals? And the guy was just growling at me, not having any of it. I suppose the moral to the story is that whether it’s photographing some ex-convict, white supremacy guy on the Greyhound in the middle of the USA or a traveller in Somerset, there are nice people – well, I can’t say the white supremacist was nice, but he was reformed, he had tattooed over his swastika with Jesus – a villain with a heart of gold. I think that middle-class men on the street are tricky because they’re just so normal.

SC: Maybe big cities have more social taboos. Like if you pull out a camera in the city and start taking pictures of people, they’re more wary than those in the country?

IM: I’ve had it in all sorts of scenarios. I’ve had it from a middle aged DJ in a pub in Southend — the girls outside the pub say, “Oh, take our picture!” And then this guy indoors takes offense to it and comes out of the pub at me and says, “You’re not allowed to take pictures of strangers!” That’s kind of a male’s perspective – it’s about him, he’s the DJ. And if there’s someone else getting the girls’ attention – I’m guessing that’s the problem. I think the guy in Forest Gate had a different agenda: his reaction was not polite, but then again, he considered my action impolite as well. It’s kind of complicated, like why are you living here then? This is a street environment, Forest Gate. The further away from London, the easier it is.

SC: When you are shooting in London, where do you normally go to take pictures?

IM: In London, anywhere really… I did quite a lot of work in Portobello and Soho and they’re quite obvious, but last weekend I was just taking pictures at a bus stop there and I found it really difficult. The light was great, but I felt so self conscious when people are standing in such close proximity and it’s quite frustrating, It makes for great pictures, but I don’t feel that I can give myself permission to do it. There’s a time and place for everything, and then they get on the bus, and it’s gone.

SC: Describe the last photograph you took?

IM: When I was taking pictures yesterday in Shoreditch — I found a girl with yellow hair and pink eyebrows and another had tattoos on her legs and I said, “Oh I’d like to take your picture.” I asked if I could take a portrait of her against this mural – the mural happened to be a banana – I didn’t plan that. They won’t walk to take a picture; you’re lucky if they even agree to take a step. She knows she’s got a really short skirt on and this old guy wants to take a picture of her next to a banana and she looks at me and she says “I’m not interested.” [laughing]

Yeah, the picture may have had a sexual undertone. I think it’s really complex taking images and I like subtle nuances in images and I like things that have narrative…

SC: Who are some of your favourite photographers? Your favourite photos?

IM: I like that photographer Tom Woods – he’s photographing people on buses, I think he’s subtle and really sincere, it’s so authentic – you don’t have a sense of some major career game plan behind it – ahem, not mentioning names. [laughs] Chris Killip – I like him too, extraordinary photographer. He did this picture of a woman sitting at a table, she’s middle aged and she’s kind of looking off into the distance – her expression is quite trancelike, like she’s caught in a gaze – and she’s holding a man’s hand who is in the foreground. And then there’s this girl that’s in her 20’s, and she’s just got her head moved forward. The woman in the foreground is hanging onto what she’s got and the young girl is going for it: there’s this sort of sexuality and energy in the young girl while the old one has wisdom and experience and she has support of this man and now she’s holding onto something important. The composition is loose and you could turn the page and not even think of it … that’s the kind of photograph I like.