The Architecture of Leisure: Pavilions in London

By Something Curated

The delight of feeling somehow indoors while outside. A protective overhead, designed to shelter from bright rays of sunshine (or, as more often the case in England, a summer rainshower). From countryside cricket grounds to the Hyde Park gardens, pavilions are a crucial part of both London’s own history and British heritage at large. London enjoys the most green space out of any major metropolis in the world. Couple that factor with the national identification with the English garden as well as the royal history of leisure, pavilions hold a significant yet understated foundation in British culture. It’s no surprise, then, that some of the most impressive pavilions built throughout the world have called London their home, or come from British architects.

The very idea of a pavilion is tinged with a sense of regality. Coming from papilo(-n) in Latin, which translates to butterfly or tent, the etymology of the word conjures the bucolic, spacious nature of the countryside. In English culture, the word has been associated with cricket since the mid-1800s, as the structure used for changing and taking refreshments. Typically introduced in the spring and summer months, pavilions mark the return of warmer weather and new growth.

At their rural best they are a championing of breezy summertime leisure; an embracing of and mastery over the outdoors. It is surrounded by and enhances the pleasure of another favourite British past-time: gardens. The pavilion allows us to delight in the smells, the sights and the sensation of the English garden no matter what the weather. Similar to its function in the city, a country pavilion acts as a social gathering place.

Within the city, the pavilion is more of a spectacle. It typically describes a short-term architectural installation that is built with a precise function in mind, typically to commemorate the beginning of an international convention or cultural event (such as the Design Festival, Engineering Season, the Chelsea Flower Festival, or the 2012 Olympics).

There is also a sensational element to pavilions in their high cost in comparison to the brevity of their presence. Urban pavilions are competitions and celebrities: who is building which, and for how much. Hundreds of pavilions have been proposed by a sea of international architects for England’s capital, but very few are ever built. The nature of the competition, as evidenced by the Serpentine’s 16-year-strong annual contest to construct a pavilion outside the Gallery in Hyde Park, only adds to the anticipatory and spectacular nature of it all.

With the expansion of the Serpentine’s iconic pavilion programme this year to incorporate four ‘summer houses’ in addition to the 2016 pavilion by BIG (above), it is more important than ever to reflect upon the history and meaning of pavilions in London. Here, Something Curated reviews the legacy of the pavilion infatuation that has characterized British culture and London architecture and design for centuries.

The original London Pavilion (1859)

The oldest “pavilion” in London is the Old Pavilion in Piccadilly, which opened originally in the 1859 as a music hall. The theatre, constructed by the Peto Brothers with an interior designed by James Ebenezer Saunders and elevations by R. J. Worley, opened in November of 1880. As more and more buildings cropped up around it throughout the centuries, its original namesake has become increasingly oblique. Rebuilt in 1985 and again in the mid-30s, the theatre was shut down in 1981 and remained derelict until 1986, when it was gutted and converted into tourist attractions. Now home to Ripley’s museum and nearly unrecognizable to its original formation, the pavilion nevertheless instilled a sense of ardor for the structure and symbolism of the pavilion and succeeded in introducing it to an urban environment.

‘This magnificent establishment, fitted up most luxuriously and elegantly is now open. When lit up the Pavilion is really gorgeous. The Cafe and Smoking Saloons are fitted up with regard to comfort, and well supplied with periodicals. The refreshments first-class. American and Dutch Bowls, Jardin d’Hiver, Music, Promendae, and Rifle Galleries. Sarkozy will preside over the Orchestra. The inimitable Sam Collins every night – Admission free.’ – The ERA, 23rd October 1859.

Regents Place (2010) | Carmody Groarke Architects

The Regent’s Place Pavilion by London-based architecture studio Carmody Groarke was the result of a two-stage competition run by The Architecture Foundation in 2007. The original competition brief called for a new pavilion to mark the Osnaburgh Street entrance to Regent’s Place which activates and intensifies the new East-West connection afforded by the street.

Carmody Groarke, winners of the 2007 Young Architect of the Year Award, proposed a pavilion as a forest of rods that support a canopy eight metres above the street. There are pathways within the pavilion that open up the space from the inside to areas to sit and socialize as well as pass through. The pavilion changes with the time of day, the golden rods shimmering in sunlight by day and project artificial light at night-time to illuminate the way for passersby. The pavilion was completed in 2010.

BMW Pavilion for 2012 Olympics | Serie Architects

Serie Architects is an international practice founded based in London, Mumbai and China working in the diverse fields of architecture, urbanism and design. Founded by Harvard GSD alumni and Associate Professor in Practice of Urban Design Christopher Lee, the practice reflects Lee’s investment in the evolving relationship between built forms and urban development, and the projection of these forms of intelligence into spatial solutions.

Serie describes their pavilion as taking its departure point from the Victorian Bandstand, an iconic architecture of English culture.

“It seeks a similar relationship to its setting, which in practice has involved addressing questions of spectacle and presence, of the relationship to BMW’s product and service offering, and of sustainability.”

The pavilion appeared to hover over the Waterworks River in the Olympic Park, with a spectral podium that cascades water and changes lighting with the time of day. The ‘showroom’ was conceived as a series of luminescent lily pads which cars (and visitors) would traverse.

The Serpentine Pavilion (2006 – ongoing) | Various Architects

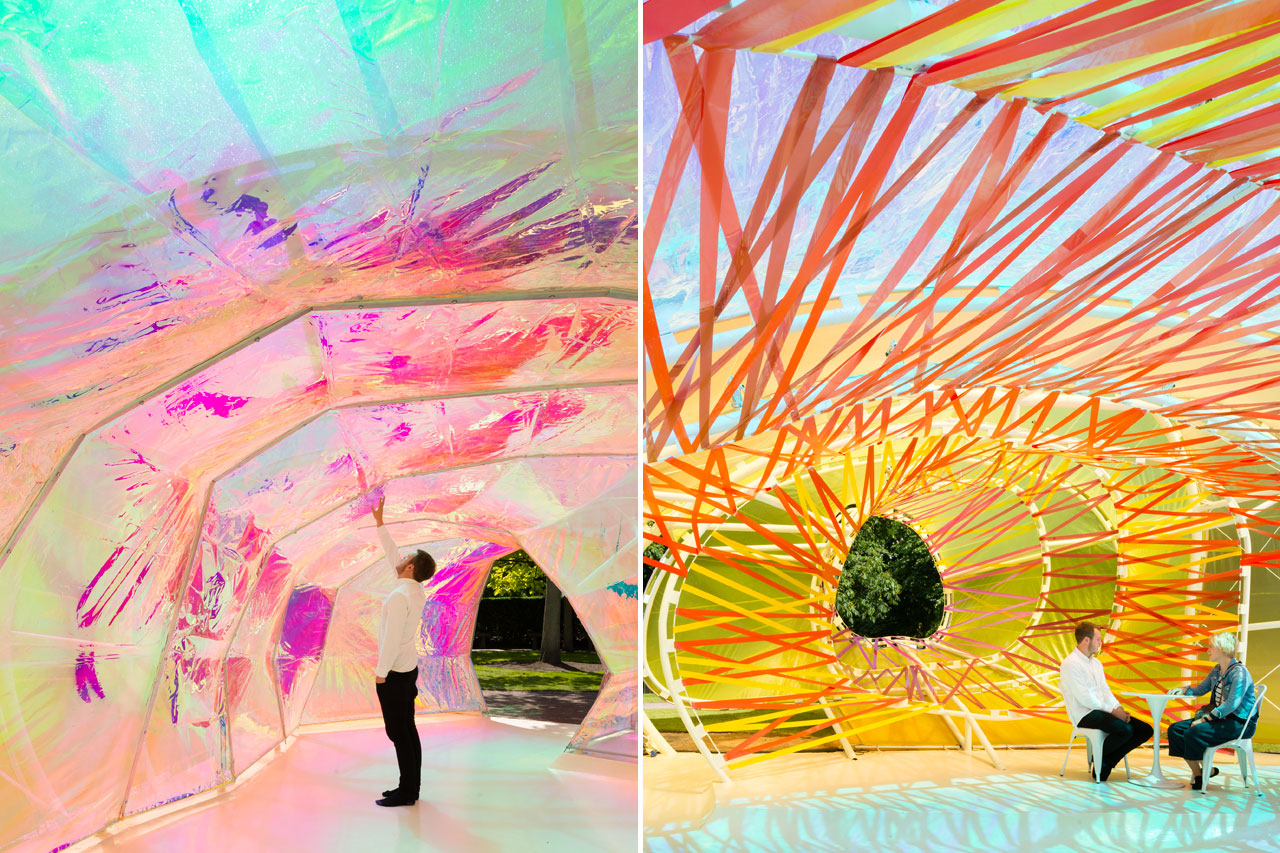

Sou Fujimoto’s cloud-like structure made from a lattice of steel poles has become an iconic sampling from the Pavilion Competition’s 16-year history, but the Serpentine has been known to feature less flashy “starchitect” work and more craft-based installations, such as the next year’s pavilion by Smilijan Radic. Radic is a Chilean architect whose 2014 pavilion was inspired by the bulbous and semi-translucent form of seashells. With a wooden patio deck, 10mm thin and membranous layer of glass-reinforced plastic that allowed light to enter into the space whilst emitting a warm glow, Radic’s very tactile, very hands-on project couldn’t be further from Fujimoto’s twinkling minimalism.

Spanish architects SelgasCano were the winner’s of last year’s pavilion competition. Their structure is something of a neon playground with large sheets of transparent and opaque ETFE, a new material for the architects, wrapped around its frame and stretched across entire sections. The result is a holographic, asymmetric, semitransparent cavelike structure that changes its appearance with the weather. Rather appropriately, the pavilion was relocated to LA following the end of the season.

View an extensive archive of the Serpentine’s pavilions here.

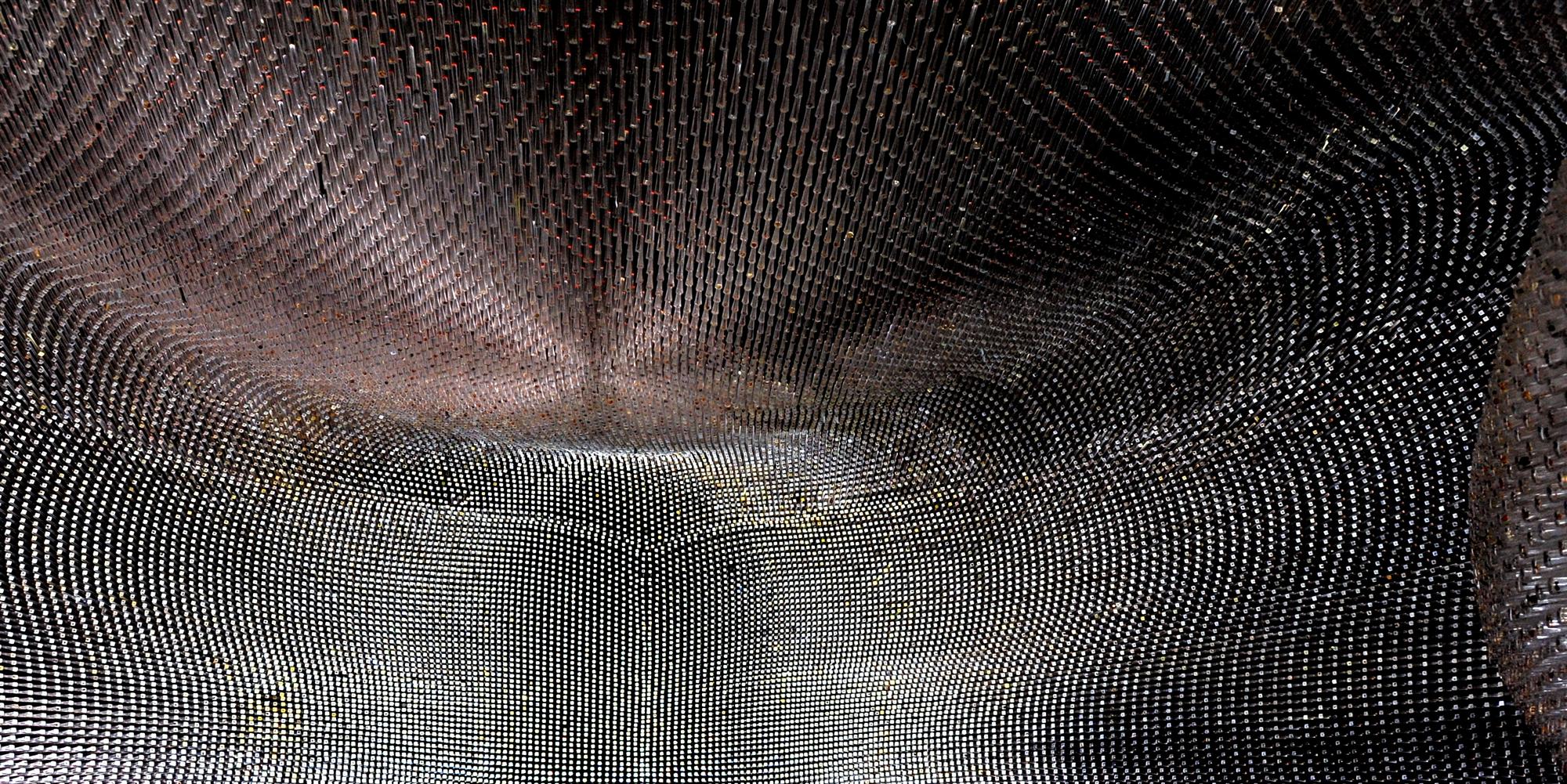

Serpentine Sackler Gallery Extension (2013) | Zaha Hadid

The 2013 extension to Serpentine Sackler is something of a permanent pavilion for London, as well as the late Zaha Hadid’s third pavilion commission from the Serpentine. Zaha’s pavilion recalls the structure’s etymology as a tent, with its undulating ceiling mimicking the flow of fabric. It is anchored by three columns that capture it at various points in the room but the ceiling climbs to 6m at the highest point, allowing daylight to spill through. In the night, the pavilion reaches an even greater splendour, with the red lights on the side of the old building connected to Zaha’s addition casting a surreal shade onto the glossy white building and the walkway below. As a restaurant and hirable events space, the structure certainly fulfills the function of its form.

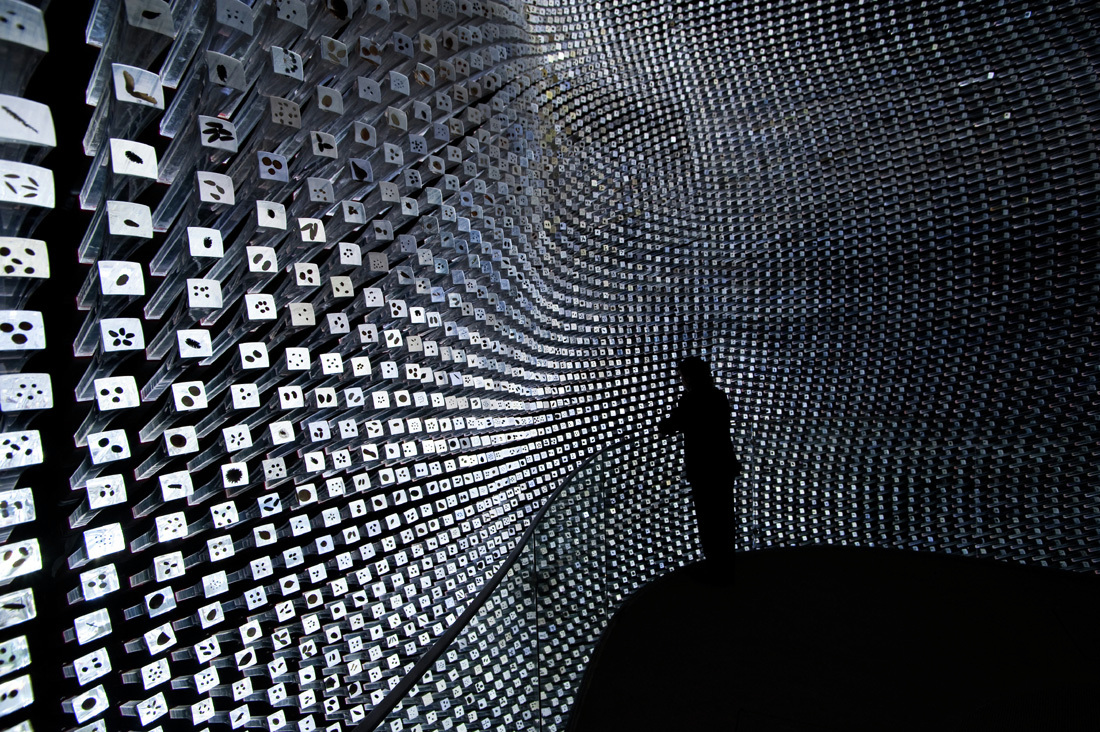

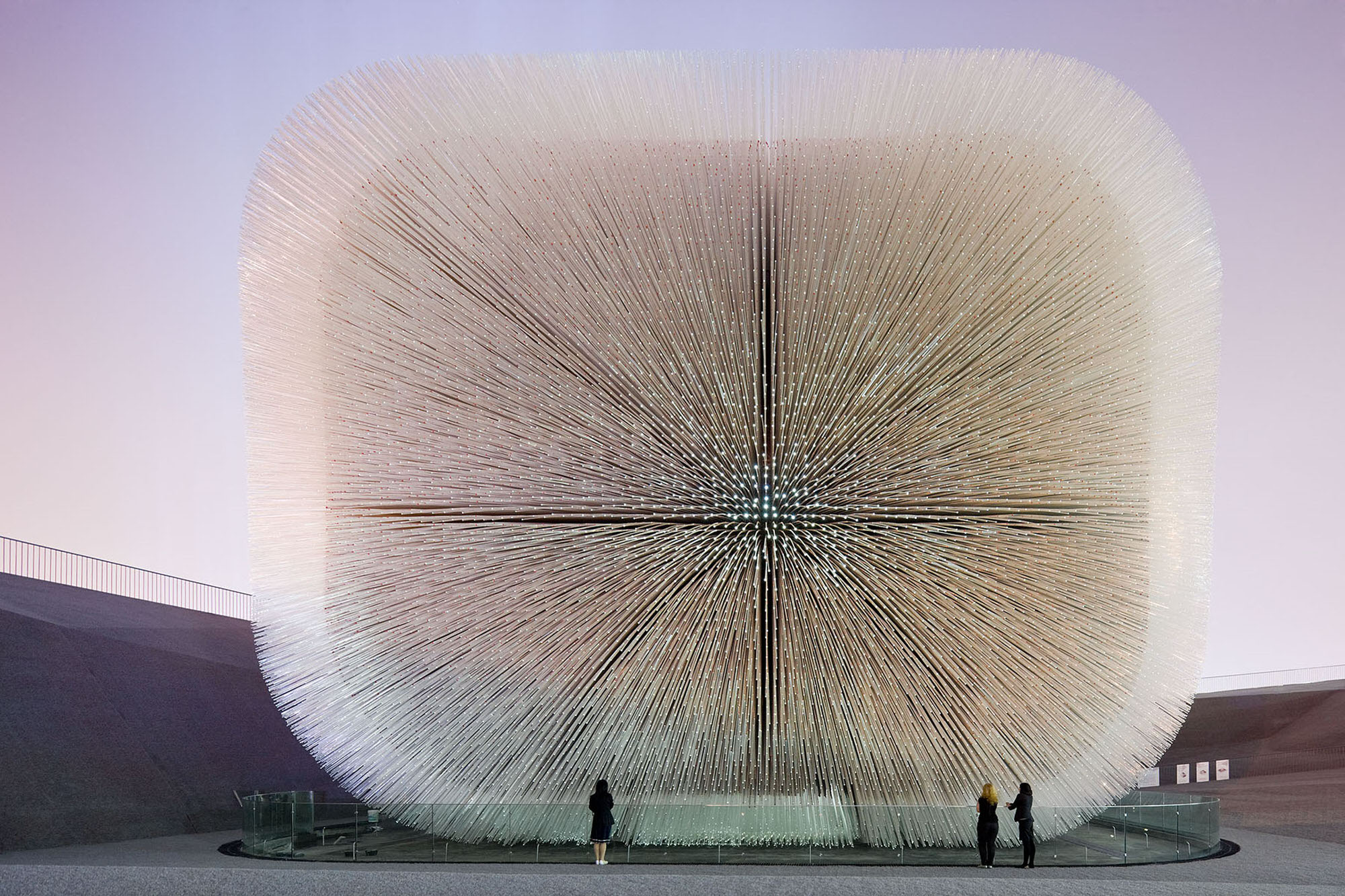

Seed Cathedral (2012) | Thomas Heatherwick

Though not technically in London, the 2010 UK pavilion for Shanghai Expo designed by British architect Thomas Heatherwick made waves in its local surroundings. Titled the Seed Cathedral, the pavilion referenced London as having the most green spaces and parks compared to all other global cities. The 60,000 acrylic rods containing 250,000 plant seeds, held in place by geometrically-cut holes, absorbed the light conditions of its surroundings as well as wind levels, which sent the hair-like rods aflutter in biodynamic waves. The cathedral absorbed pinpricks of light in the day time and reflected it back out at night, a meditative ambience overtaking its prickly hairs in the evening time.