Brutalism’s Renaissance: A Guide To London’s Concrete Giants

By Keshav AnandThere has been a significant shift in attitude towards the architectural style of Brutalism in recent years, with buildings once dismissed as obnoxious now finding themselves as objects of newfound regard. Over the past three years, major cultural institutions, like the Barbican, RIBA and Tate Britain, have hosted popular exhibitions celebrating the movement. Based on an appreciation for human interaction and a desire to democratise architecture, Brutalism was born from utopian visions. The often-contentious buildings, with their intimidating slabs of concrete and austere block forms, are enjoying somewhat of a renaissance.

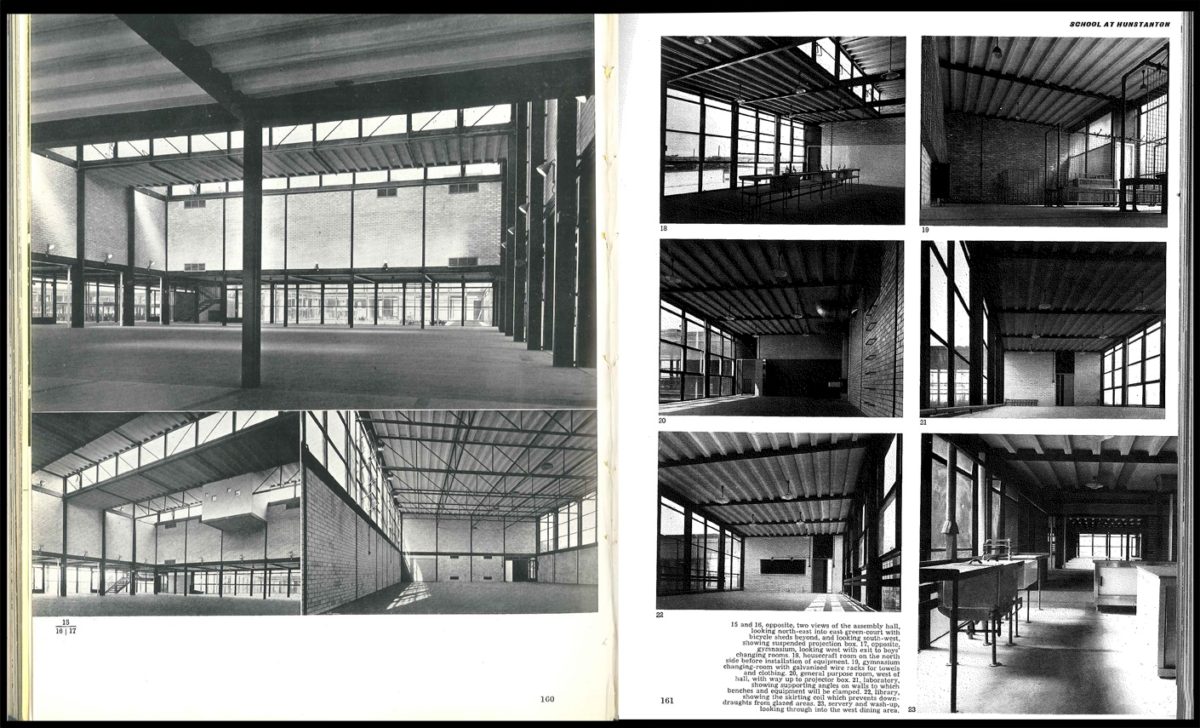

When it comes to Brutalist architecture, London is home to some of the finest examples. Rooted in Modernism and first evident in the work of Swiss architect Le Corbusier in the late 1940s, the term Brutalism was first used by Swedish architect Hans Asplund in 1950. Shortly after, architectural critic Reyner Banham used the term more widely in his essays to refer to the work of English architects Alison and Peter Smithson, who created the iconic Hunstanton School in Norfolk. Their style rebelled against the formal architecture of the 1930s and 40s.

The term came to refer to the functional raw concrete buildings emerging in the UK, and London in particular, in the post-war period. It placed an emphasis on materials, textures and construction as well as functionality and equality. The Brutalist architects challenged traditional notions of what a building should look like, focussing on interior spaces as much as exterior. They unapologetically exposed their buildings’ construction, making aesthetic features of service towers, plumbing and ventilation. Due to the relatively low cost of concrete, the style was popular for rebuilding government buildings and providing social housing.

RIBA describes the aesthetic as consisting of rough unfinished surfaces, unusual shapes, heavy-looking materials, massive forms, and small windows in relation to other parts. Due to their sheer scale and material bulk, many Brutalist buildings have escaped looming campaigns for their eradication, owing to enormous demolition costs. Inevitably, these longstanding constructions undergo several refurbishments during their lifetime; today, many Brutalist structures in the UK are listed buildings. Something Curated takes a look at London’s most remarkable examples of the architectural style.

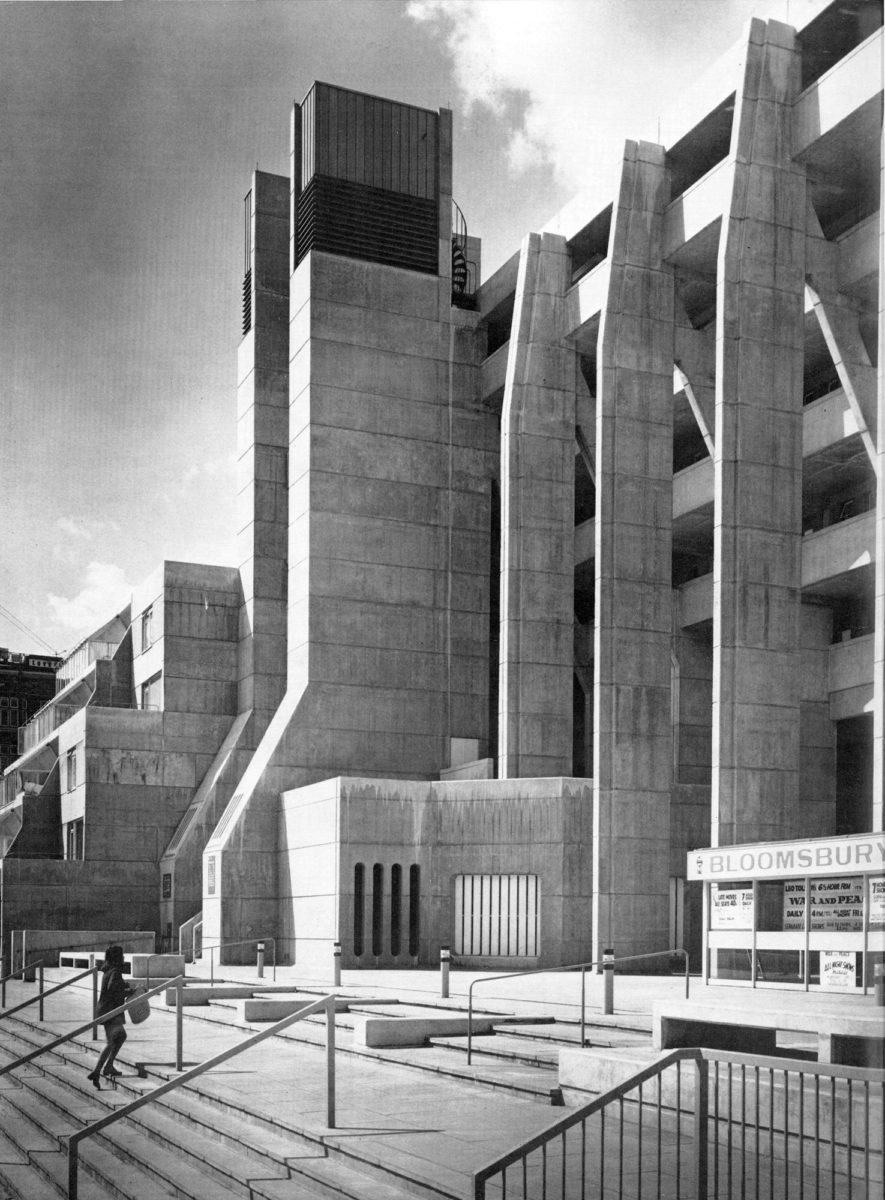

The Brunswick Centre || Patrick Hodgkinson

The Brunswick Centre is a grade II listed residential and shopping centre in Bloomsbury, located between Brunswick and Russell Square. Patrick Hodgkinson began to develop the concept for the site with his study of the Loughborough Road Estate in Lambeth by the LCC, where Sir Leslie Martin was the chief architect. Hodgkinson and Martin then collaborated in 1957 on a scheme for St Pancras Borough Council. It was initially planned as a private development at a time when private, mixed-use development in the UK was rare. Hodgkinson, who passed away earlier this year, conceived the Brunswick as a modern London village, with family homes, a cinema, shops and even health facilities, but it was not to be.

Various attempts have been made to resurrect the Brunswick, but it was only in the late 1990s that someone succeeded. Part of the reason current owners Allied London managed it was that they invited Hodgkinson back. One of the most remarkable things about the Brunswick’s renaissance is how simple it was. In essence, much of what they have been doing is what the architect intended to do in the first place. The shopfronts have been spruced up, and a Waitrose has been added, and, perhaps most prominently, the complex has been cleaned and painted. The Brunswick’s revival suggests that some of British architecture’s radical experiments in the 1960s and 70s were perhaps condemned too quickly.

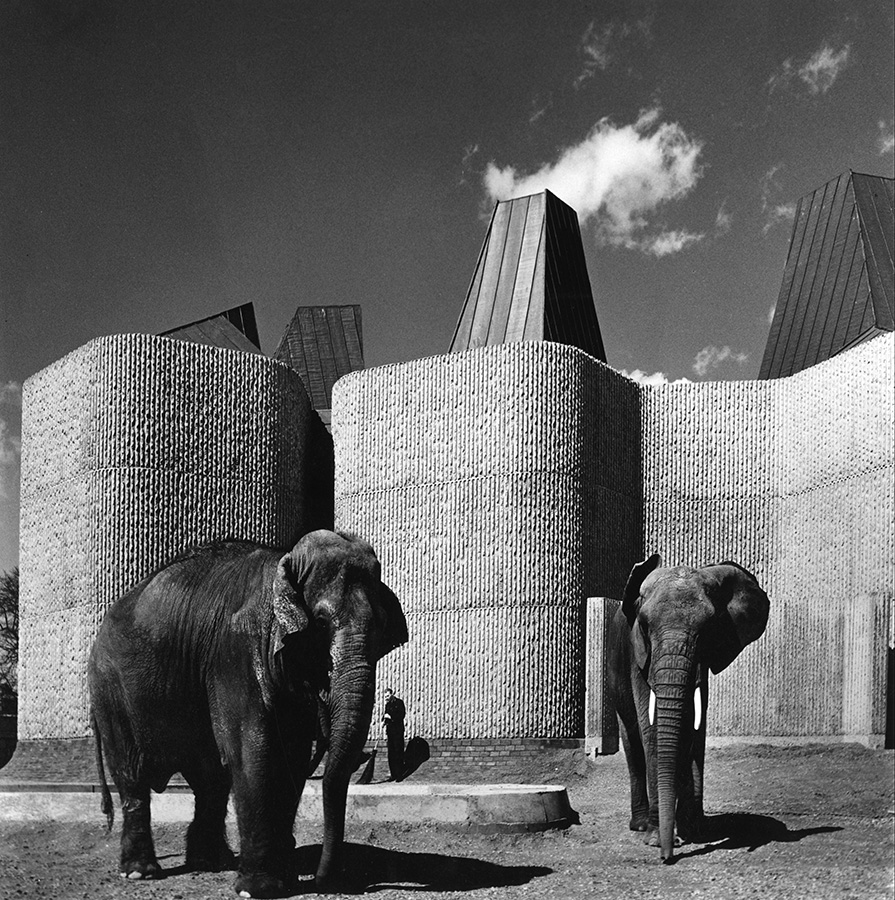

Elephant & Rhino House, London Zoo || Sir Hugh Casson

The Elephant and Rhino House is one of the earliest and most architecturally significant buildings constructed at London Zoo, following a redevelopment plan in 1956 commissioned by Lord Zuckermann. With walls rough like the skin of an elephant, this Grade II listed landmark was designed by Sir Hugh Casson. Though the elephants have long since moved to London Zoo’s partner organisation, Whipsnade, the exterior of the building is said to resemble the massive animals gathering around a waterhole.

Unusual concave forms were designed to house four elephants and four rhinoceroses in paired pens, each with access to sick-bay pens and to moated external paddocks. The structures feature heavy double doors reached via steps for the public, and slit windows to staff areas stylishly incorporated as skylights. Interestingly, since the elephants’ departure, Casson’s creation has housed various animals of diverse sizes, from camels to porcupines.

Trellick Tower & Balfron Tower || Ernő Goldfinger

Ernő Goldfinger moved to the UK in the 1930s, and became a key member of the Modernist architectural movement. Completed in 1967 in Poplar, Balfron was the first chance for the Hungarian-born architect to realise a vision for large-scale public housing that had been in development for over 30 years. The architect drew inspiration from the Modernist principles of Le Corbusier’s Unite d’Habitation for the tower’s dwelling units. Standing at 322 feet tall, the Trellick Tower’s Brutalist architectural style dominates the immediate skyline. It is loosely based on Goldfinger’s earlier and smaller Balfron Tower of similar style and construction.

One of the most unique features of Trellick Tower, besides the distinct separation of service from dwelling, is the method for which the flats are accessed. The main volume features the dwelling units, while a thin service tower connected at every third floor to the main tower houses the stairs, lifts, and mechanical plant. Nine different types of two level flats are designed with the main entry lying on every third floor that connects to the service tower. Interestingly, while a few flats are privately owned, the majority of the units are still utilised as social housing as originally intended.

102 Petty France || Sir Basil Spence

102 Petty France, an office block in Westminster overlooking St. James’s Park, was designed by Sir Basil Spence for Fitzroy Robinson & Partners. Completed in 1976, it was well known as the main location for the UK Home Office between 1978 and 2004 when it was 50 Queen Anne’s Gate. After a £130 million refurbishment, it became home to the Ministry of Justice in 2008.

The corner tower dominates the approach from Tothill Street, which leads to the west front of Westminster Abbey. The structure embodies most things about the Brutalist movement, the scale and mass of the building which makes no attempt to fit in with the Georgian houses of Queen Anne’s, the heavy use of concrete, and lastly, controversy surrounding the building’s architecture.

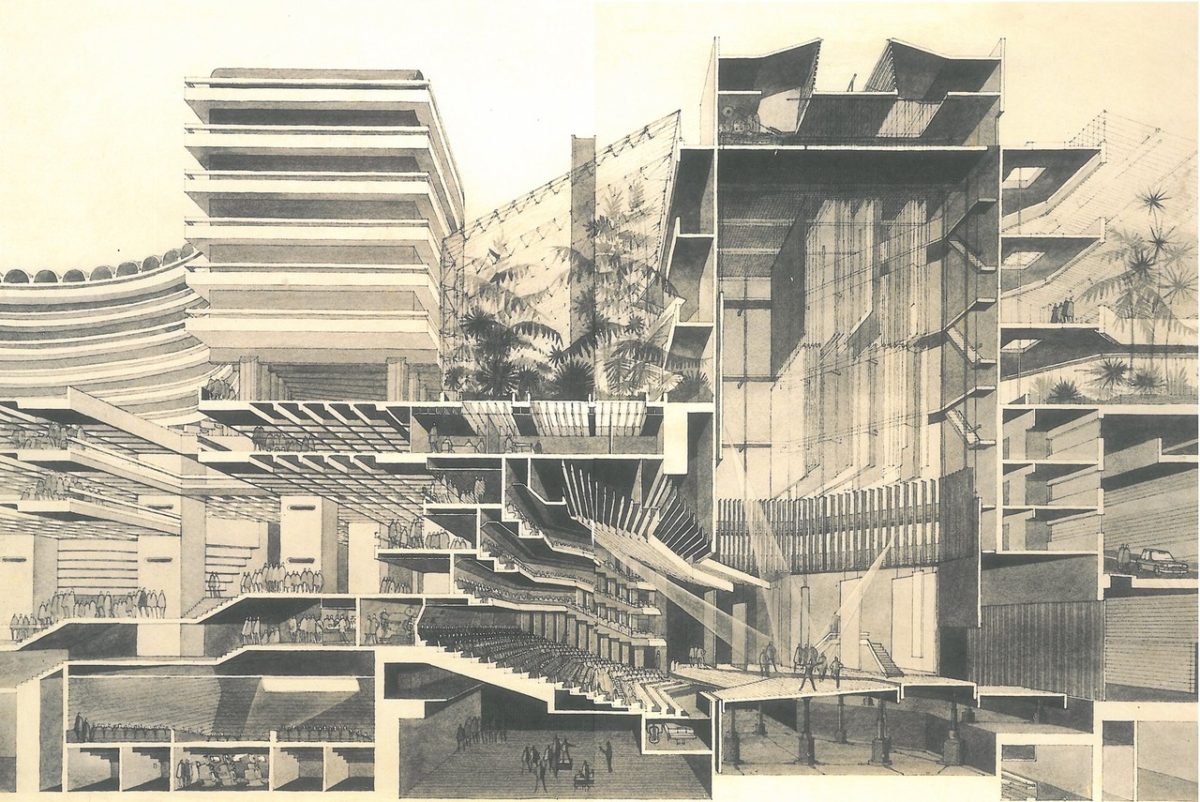

The Barbican Centre || Chamberlin, Powell & Bon

A Grade II listed building, the Barbican is Europe’s largest multi-arts venue and one of London’s best examples of Brutalist architecture. It was developed from designs by Chamberlin, Powell and Bon, a team of three young architects who had recently established their reputation by winning a 1951 design competition for the nearby Golden Lane Estate. The project was part of a utopian vision to transform an area of London left devastated by bombing during the Second World War. The Centre took over a decade to build and was opened by The Queen in 1982, who declared it ‘one of the modern wonders of the world’ with the building seen as a landmark in terms of its scale, cohesion and ambition.

With its coarse concrete surfaces, elevated gardens and trio of high-rise towers, the Barbican Estate offered a new vision for how high-density residential neighbourhoods could be integrated with schools, shops and restaurants, as well as world-class cultural destinations. Its striking spaces and unique location at the heart of the Barbican Estate have made it an internationally recognised venue, set within an urban landscape acknowledged as one of the most significant architectural achievements of the 20th century.

180 The Strand || Frederick Gibberd

Frederick Gibberd’s Portland stone building has become a hub for art, culture, style and fashion in recent times. The British architect, who studied at the Birmingham School of Art, was influenced by the work of Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe, and F. R. S. Yorke. He set up his practice in 1930, designing Pullman Court in Streatham Hill, a housing development which launched his career. With an arts programme curated by The Vinyl Factory, his iconic Brutalist building provides a new space to house creative industries, where innovative businesses and visionary talents can collaborate.

The Hayward Gallery are presenting the gallery’s only major offsite exhibition, opening later this month, during their refurbishment, within the iconic building on the Strand. ‘The Infinite Mix: Contemporary Sound and Video’ features audiovisual installations by leading British and international artists, including Martin Creed, Jeremy Deller and Elizabeth Price, to name a few.

The Hayward Gallery || Norman Engleback, Ron Herron and Warren Chalk

The Hayward Gallery, named after Isaac Hayward, a former leader of the London County Council, located within the Southbank Centre, attracts over six million visitors annually. Interestingly, the gallery does not house any permanent collections but hosts regular temporary exhibitions. Built by Higgs and Hill and opened in 1968, its massive scale and extensive use of exposed concrete are typical of Brutalist architecture. The initial concept was designed as an addition to the Southbank Centre arts complex by team leader Norman Engleback, assisted by Ron Herron and Warren Chalk. Chalk developed the site plan and connective first floor walkways, while Herron worked on the acoustics for the Queen Elizabeth Hall.

In 2003 the building was remodelled by Haworth Tompkins architects who added a larger glass-fronted foyer and a new oval shaped glass pavilion. The gallery, Queen Elizabeth Hall and Purcell Room are now closed and are undergoing a major regeneration led by Feilden Clegg Bradley Studios. The first stage of the project, refurbishing and adapting the existing buildings to the demands of the 21st century, is set to be complete by the end of 2017.

1 Kemble Street || Richard Seifert

Completed in 1966, 1 Kemble Street, originally known as Space House, was designed by Richard Seifert, whose buildings include hotels, railways stations and office blocks. Known for his work in the 1960s and 70s, he was a notable influence on London’s architecture during the period. At 16 storeys high, it is the less well-known sibling of Centre Point. Although their forms differ, they share many similarities. Both were designed by Seifert’s practice for Harry Hyams’ Oldham Estates around the same time, and use similar construction techniques and materials with the same angular precast concrete structure.

Rumour has it that Space House was originally designed as a luxury hotel and was intended to be twice as high. A discrete bridge links the project to a smaller, plainer slab block fronting Kingsway. Each of the modelled concrete cruciform units is cross-shaped and has a dimension of exactly ten feet in width and height and three feet in depth. Notably, in 2004 Sturgis Associates undertook a major refurbishment of 1 Kemble Street.

Centre Point || George Marsh

Comprising of a 33 storey office tower, a nine storey block to the east including shops, offices, retail units and maisonettes, and a linking block between the two at first-floor level, Centre Point occupies 101–103 New Oxford Street and 5–24 St Giles High Street. Completed in 1966, it was one of the first skyscrapers in London. The building was designed by George Marsh of the practice R. Seifert and Partners. The precast segments were formed of fine concrete utilising crushed Portland stone from Dorset. It stood empty from its completion until 1975, and was briefly occupied by housing activists in 1974.

In October 2005, Centre Point was bought from the previous owners by commercial property firm Targetfollow. The building was extensively refurbished and has since been purchased by Almacantar, who have received planning permission to further refurbish the building. Work began last January on converting the Brutalist office block into luxury flats. The project is being overseen by Sir Terence Conran’s Conran & Partners, ready for occupation by April 2017 in time for the new Crossrail station at Tottenham Court Road.

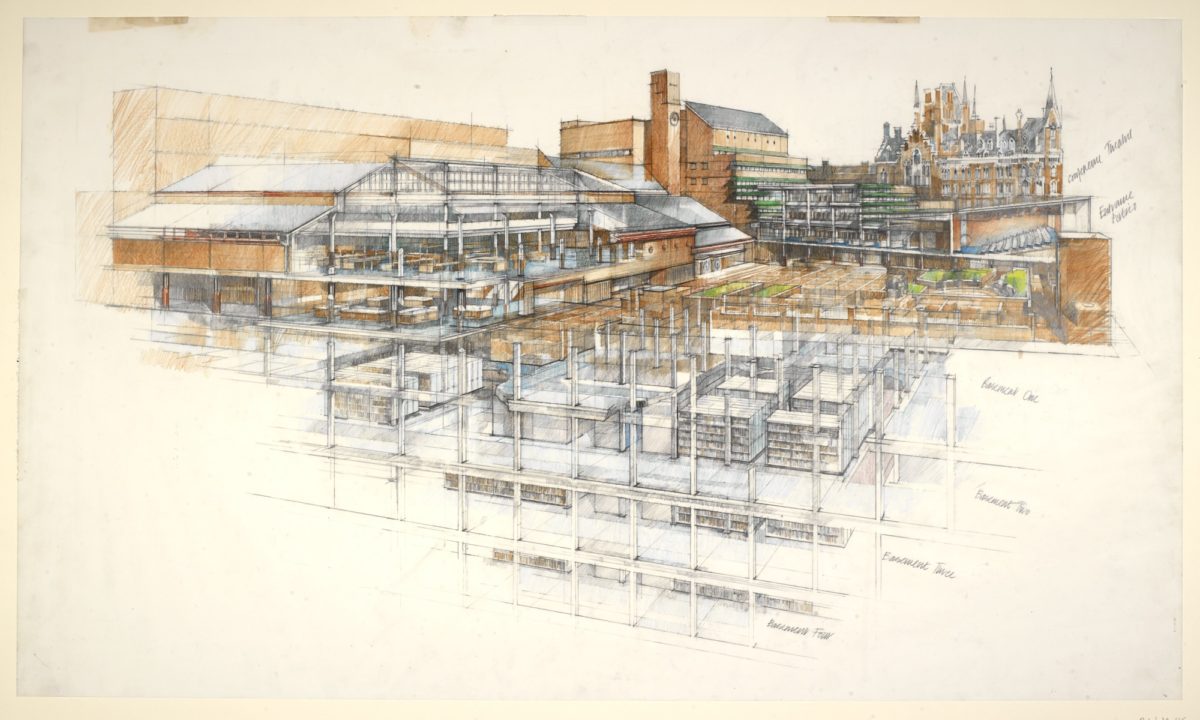

The British Library || Colin St John Wilson

The British Library was awarded the highest heritage honour last year, receiving Grade I-listed status. Though the building does not boast the typical concrete exterior, Colin St John Wilson’s creation fits the criteria of a Brutalist structure, featuring unusual shapes, massive forms and small windows in relation to the other parts. The institution, on Euston Road was opened by the Queen in June 1998 – more than 20 years after it was first approved and at £350m over the original budget. Initially, The British Library was part of the British Museum, but by act of parliament became a separate institution in 1973.

The library extends deep underground to hold an ever-expanding collection, around 150m objects growing by an extra 1.5m items a year. The architect, who was reputed for his commitment to public buildings, died in 2007, somewhat bruised by the years of controversy surrounding his seminal project. The history of the building, delayed by on-going political meddling, was infamous. On completion, the striking redbrick library, with its massive courtyard filled with sculptures, was denounced as an eyesore and waste of money by politicians and members of the public – a far cry from its celebrated status today.

Feature image via Studio Esinam & Rory Gardiner

Text by Keshav Anand