Interview: Tom Ellis At The Wallace Collection

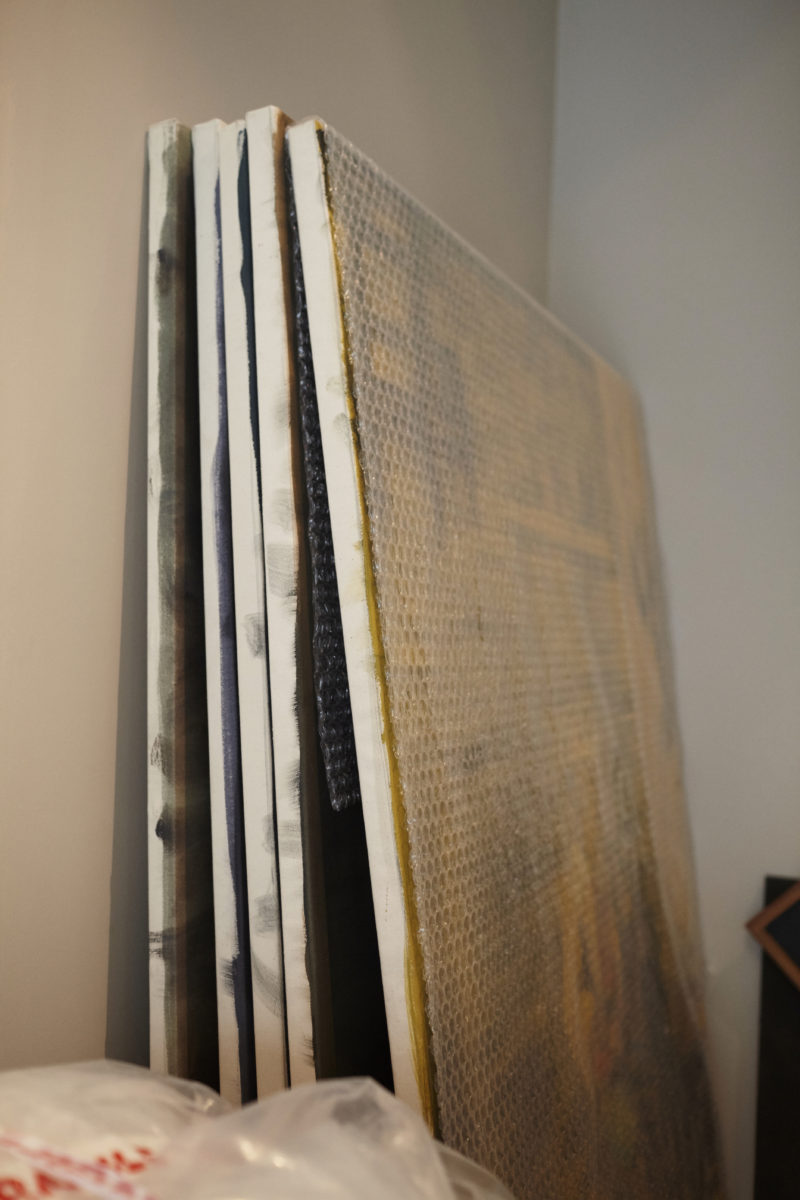

By Something CuratedBritish artist Tom Ellis has created a series of works pairing his figurative paintings with self-made furniture for a new exhibition at the Wallace Collection. The project initiates a thoughtful dialogue between the historical collection and contemporary art practice. Presented in the former home of the Seymour family, Marquesses of Hertford, the Wallace Collection evokes a domestic atmosphere, resonating with Ellis’ approach. Typically furniture and paintings are found together in a domestic setting or scene, and by combining these elements, Ellis explores concepts of public and private space, examining how the status of his work’s setting impacts the objects displayed within it. Ahead of the exhibition’s opening, Something Curated caught up with the artist at the Wallace Collection to discuss his new work, how the show came about, and the importance of self-assessment.

Something Curated: Could you tell us, broadly speaking, about your practice, and the subjects you address in your work?

Tom Ellis: The subject matter is an interesting one. With figurative painting, there’s a tendency to always see the narrative or the descriptive content as the key message within the work. For me, that’s a given, as soon as you make a figurative painting you’re inevitably going to pull forward some kind of episode, which, because of the way the human mind works, will offer some narrative trajectory that people latch onto. With this show, the choice of the shoemaker was very specifically a solution to that. I wanted a subject with a narrative that told or retold of the working process. The subject matter, which is often the focus of figurative painting, is secondary to me. It’s one of my key ambitions to reconfigure the work so that the narrative trajectory gets softened. It’s a complex ambition but it’s a very specific one that I’ve had for a long time. I think because I’ve had so long to prepare for the show, I’ve really been able to track down the solution in this work.

SC: Congratulations on your show at the Wallace Collection. Could you tell us a bit about how it came about and the process of preparing for it?

TE: Thank you. The original contact came through a German journalist who had interviewed me. Shortly before, she had interviewed Christoph Vogtherr after he had been appointed as Director at the Wallace Collection – that was big news in Germany. At the end of my interview, we got talking and I said, “I’d love to get in touch with Christoph.” She sort of pulled a face implying that it was very unlikely to bear fruit, but I had no expectations; I was just keen to talk to him. So she sent an email, and amazingly we got a reply within twenty minutes saying, “I’d love to meet Tom.”

Many months passed, and then the journalist and I went to meet Christoph, and we had this great conversation. I had no ulterior motive – I just felt a real affinity with the Wallace Collection. I think he saw that. And it was good timing, because at that point they were addressing whether or not to continue their dialogue with contemporary art. I think we both quickly saw there was a real resonance between my work and the collection. In a way, we saw this duality between applied art and the paintings as mirroring something more complex. And that’s why I’ve been drawn to pairing the furniture and paintings, not because I have a background in furniture making as a paid employment, but because I knew it would disorientate and debase the painting projects in a way that resolved my concerns with the figurative works.

SC: How has The Wallace Collection’s historical context informed the work you have produced for the show?

TE: It’s funny, it was back in 2011 when our first conversation happened, and it wasn’t till 2013 that we were really talking about an exhibition. That got delayed because of government cut backs and other things, so it really did drag on. It was frustrating for all those involved but it was also enriching for the project. I was gestating the idea of the show for a very long time. Things like the provisional wall covering emerged early on, I remember considering it as a possibility for the first time in 2013. It was quite fascinating to have such a length of time to steep yourself in a project.

I always said to the Wallace Collection, “Until you give me a date, it’s all hypothetical and I won’t start work.” I wasn’t threatening them but as an artist, you won’t spring into action physically until something is really concrete. Particularly with such a rich and culturally loaded setting as this, to start to pretend to work for it on the basis of maybe getting the show, just isn’t how I work. So work, as in physical production, actually only began at the end of last year. But obviously loads of ideas preceded that stage.

Something that’s really interesting that’s emerged out of this is that I used to, almost with a sense of disappointment, see my painting and furniture practice as inevitably operating as installations, and I didn’t really want to be an installatory artist. I wanted the work to exist independently of its surroundings; I don’t want it all to have some prescriptive dogma behind it. And what I’ve realised from working here, is that my strategies are modes of decontextualisation and detachment, rather than contextualisation. So the runners and provisional white walls could end up anywhere. I’m using these runners as a framework to essentially install my paintings despite the location, rather than attempting to embed them into their setting.

SC: Could you tell us about some of your most memorable projects or exhibitions?

TE: [ SPACE ] gallery in 2009. It was the first show that Paul Pieroni curated there – he’s one of the essayists for this show actually. That was the first time I presented a full and fairly large-scale exhibition of paintings and furniture in combination. That was a really pivotal show. And shortly after I did a show at Kunsthalle Winterthur, Switzerland, where I represented very large-scale blow-up paintings, and there was a small furniture component to that exhibition too. Those were really key shows I think.

SC: Interestingly, you also make furniture. Could you share your thoughts on the relationship between art and design? What differs in your approach?

TE: I deliberately remove the functionality of the seats, and the tables really aren’t serviceable. The pieces for this show have specifically been pulled down so they are ambiguous; they fit between furniture, sculpture and painting in a very literal way. They are intentionally left in this liminal state, where you can identify properties in them but you can’t necessarily place them. As a painter you have to invent everything, so it’s a very different existential act to making furniture, where I can essentially make these again and again. I can measure the pieces, cut the wood, put it together – it’s actually a very predictable process comparatively.

Whereas with most painting, apart from the purely method-based practices, there’s an area of chaos and chance which you’re not in control of. I really like the play between those two things. It’s just a totally different experience making these types of objects, and I’m embedding that in the same practice. I’m kind of trying to reduce the significance of the whole experience, which in a way could be seen as cheating the audience, but I would say that it’s almost a thinking error to overinvest significance in things. So changing the dynamic by including the furniture, runners and provisional walls, are means to take everything down in terms of the work’s significance.

SC: Could you tell us about some of the external references that have informed this body of work?

TE: I think the most obvious one is this image of the shoemaker, drawn from a painting by David Teniers the Younger, who’s represented in the Wallace Collection. This painting that I’ve transcribed is not featured in the collection, which is an interesting thing. Christoph made it clear from the beginning that I didn’t have to quote from the collection, and I totally agreed. Yet another historical museum embraces a contemporary artist, and they go into the collection, find something they like, and make their own kind of version of it. It’s a very common practice when museums make a tie up with contemporary art, and I think we both, Christoph and I, felt there was a much richer dialogue to be had, which wouldn’t be served by me doing that.

But at the same time, I’ve been working with images from the Wallace Collection for many years, so I knew there was a strong likelihood that I would inevitably want to. I think working with David Teniers the Younger, who’s in the collection but this painting isn’t, struck a balance, embracing that push and pull between the fact that the Wallace Collection is a source of stimulation for me but at the same time, it wasn’t a very literal connection.

SC: Which contemporary artists do you think are doing interesting things right now?

TE: I think there are lots actually. In terms of bigger names, I think Michael Krebber is a really interesting artist. His approach to the ideas of work and investment, and the push and pull between meaning and meaninglessness is fascinating. There are quite a few younger British-based painters who I think are really interesting. In terms of figuration, Sigrid Holmwood, Lynette Yiadom Boakye and Laura Lancaster are all doing great work.

SC: What do you think is unique about London’s art scene? And what do you think the city offers artists?

TE: I have a small studio in London and a studio in Essex, but I essentially feel like a London-based artist. I think whether you’re an artist or any person living here, the sheer diversity and unruly breadth and width of it makes it such an extraordinary city. I think even in the last few years we’ve seen amazing things happen, even like the election of Sadiq Khan, which shows London is a really interesting, vibrant, forward-thinking and powerful city. I was born here and I’ve lived here all my life, so it’s a natural place to be. It’s definitely a challenging place to be an artist and in a way it’s largely luck and other things that allows you to survive I suppose. I think the fact it’s challenging is a hindrance but also motivational for young artists.

SC: What is your daily work routine like? Are you based mostly in the studio or do you tend to move around a lot to produce your work?

TE: It’s amazing how many meetings you end up having when you’re doing something like this. There’s a lot of time given to meetings. But generally, I would say I go to the studio at 9.30am and I’ll leave around 5pm. I do quite a regular working day actually, and I have a family, so obviously that has an impact. I think my life is a lot more organised and predictable because of that dynamic. I have come to embrace that stability, and it’s actually spurred my work.

SC: In regards to materials, are there certain mediums you gravitate to and why do you think that is?

TE: In terms of painting, I would say that since 2009 the larger works have been acrylic but I will make preparatory paintings, or in the case of this show, one painting, in oil. With the furniture, I worked in wood for a long time and then recently, working with Rocco Turino at London Sculpture for the last few years really opened up working with metal. That’s been amazing because metal offers such a different way of working. They say that architecture is the art of navigating from the vertical to the horizontal, and in a way, furniture is the same thing – it’s architecture on a small scale. With metal you have this ability to just bend stuff. It’s a rewarding thing to be able to just stick something into a vice and reshape it. Obviously it’s not impossible in wood but it’s difficult and very different.

SC: How did you get into this field? What was your journey?

TE: Academically, I wasn’t particularly strong at school. Art was the first thing where I really started to experience some success, and I think that just drove me on. So from the age of eight, I decided that I was going to be an artist. It sounds slightly ridiculous. I was really lucky – I had a string of fantastic art teachers who encouraged me, and I ended up getting a scholarship to a school with a decent art department. So it’s been a lifelong thing. Being an artist is fascinating – you have so many ups and downs and it’s just like a marathon – you’ve got to hang in there. I have come to enjoy the rough times as much as I enjoy the high times actually. All this work comes out of the difficult periods as well as the good.

SC: What is a piece of advice you would give to an aspiring artist?

TE: You should look closely at what you do and make sense of it. Once you make sense of what it is you’re doing, everything will follow after that. A lot of people always try to correct themselves, and it’s very easy as an artist to want to improve this or that, but sometimes it’s best to just stick with it. No one’s life goes quite the way they think it’s going to go, and art is at it’s most fascinating when it mirrors that. Embrace and embed what you might think are your weaknesses into your work, and turn them into your successes. I think it’s a powerful strategy to keep moving forward. Above all, follow your instincts.

SC: Which area of London do you live in and what drew you there?

TE: I live in East London, Forest Gate specifically, and I’ve been there since 2001. Just recently, you can see more people are cottoning onto it as a place to live, and it’s not a bad thing because you get good pubs, better places to hangout. It’s an interesting area – it’s still got that East End charm and it’s so culturally diverse. There’s a real breadth of attitudes and no one feels over entitled to the area, and I think that gives it something quite special.

SC: Favourite restaurant?

TE: The Marksman. It’s co-owned by a friend of mine, Tom Harris. He’s a Michelin-starred chef who has taken on his own restaurant with another friend, Jon Rotheram. I ate there last week, and I think it’s really exciting what they’re doing.

SC: Favourite place to shop?

TE: I needed a suit for the show’s opening and my wife recommended Folk. I absolutely love it. I love the fact that they’ll make the exact suit I bought in a different fabric next year – it’s totally simplified my fashion choices.

SC: Favourite place to relax?

TE: Home.

SC: Favourite holiday destination or where would you live if not London?

TE: For relaxing, Cantarriján in southern Spain. And New York for living.

Tom Ellis: The Middle at the Wallace Collection

15 September – 27 November 2016

Interview by Keshav Anand | Photography by Elliot Kennedy