Interview: Judith Clark, Curator & Exhibition-Maker

By Something CuratedAustralian-born and raised in Rome, Judith Clark is a curator and exhibition-maker based in London. She moved to the city to study Architecture at the Bartlett, and later, the Architectural Association. She is currently Professor of Fashion and Museology at the London College of Fashion, where she teaches on the Fashion Curation masters programme. Since setting up her gallery in 1997, Clark has curated over 40 exhibitions, including projects with Artangel, Selfridges, the Victoria & Albert Museum, the British Council and Louis Vuitton.

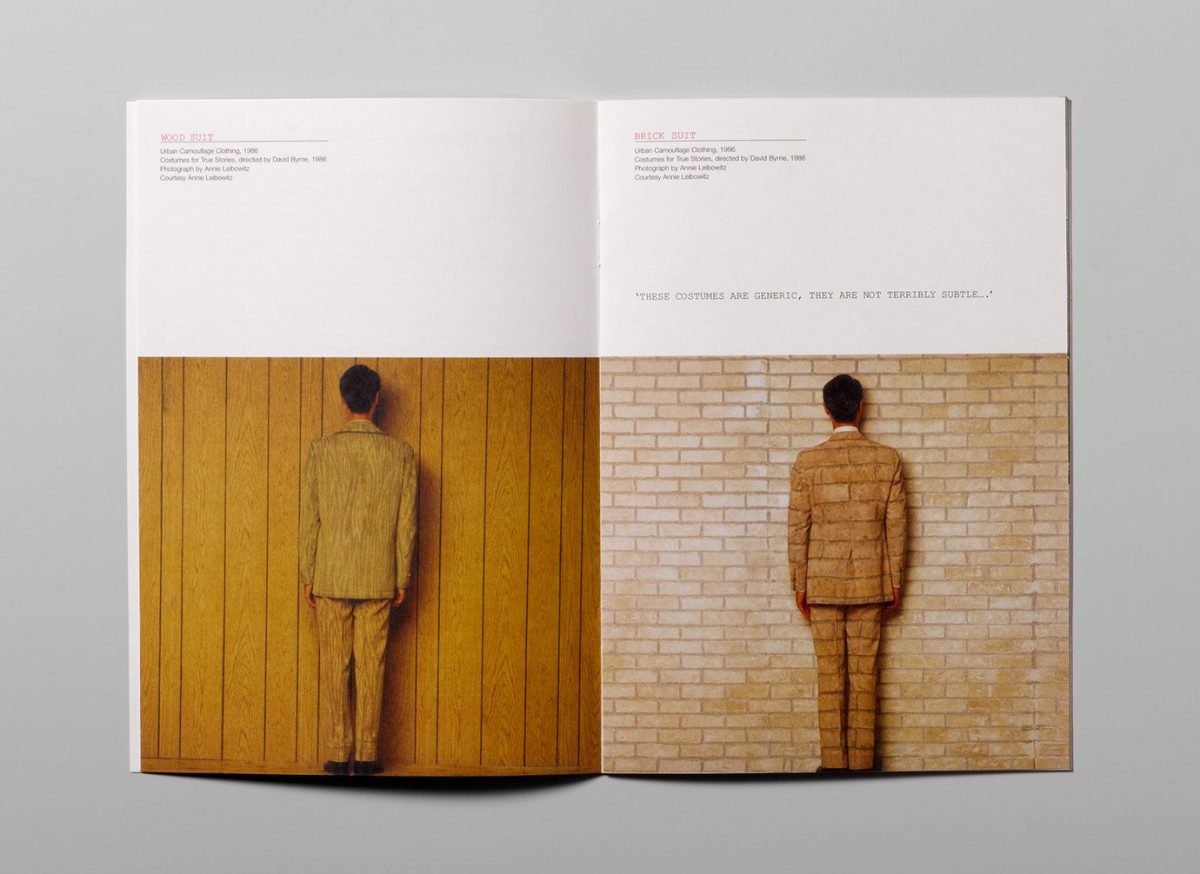

For her latest project, Clark worked in collaboration with her husband, psychoanalyst Adam Phillips, to produce an exhibition at the Barbican Centre. The Vulgar: Fashion Redefined takes varied literary definitions of ‘the vulgar’ as a starting point. Intertwining historic dress, couture and ready-to-wear fashion, manuscripts, photography and film, the carefully crafted show illustrates how taste is a mobile and continually varying concept. Something Curated caught up with Clark during the run up to the exhibition, opening in October, to learn more about her work, collaborative relationships, and the changing perceptions of fashion curation.

Something Curated: Would you say there is a directional vision or ethos that ties together the various strands of what you do?

Judith Clark: Absolutely. If you consider how recently dress and textile departments were hardly known, hardly funded within museums, you see that there is an inevitable struggle that underlies what I (and my colleagues) do. Until very recently it was not possible to study a subject called Fashion Curation. What I love about it, in a way, at this particular moment in time is that it is still a discipline in flux, it is still possible to make it ones own – bringing to it all the idiosyncrasies of ones previous experience and educational or professional past.

SC: How do you approach a new project? Is there a method of working that you have established?

JC: By browsing books and images, it depends what comes first venue or theme. If it is the venue I start looking at the venues history, as I am so interested in exhibition histories there are always remains of how the space has been used before that is interesting to me. If it is the theme I look at the associated fashion and styling and how it is represented, what were the backdrops, and start to find clues that apply as much to the built project as the curatorial one.

SC: How do you feel you are unique in your approach?

JC: I guess in this holistic approach. I think by working in the round. I don’t create lists and as such I am an exhibition-maker and not a curator. I always think simultaneously about how the silhouettes will be shown, how to subdivide the space, what the environment will be and populate it at the same time. It comes from the dress, but obliquely perhaps. I am not a dress historian, but I couldn’t exhibit anything else, it is a strange combination.

SC: Is there anyone in particular whose work you are inspired by, in your field or elsewhere?

JC: In this discipline we are always relying on the opportunities created by those who have come immediately before us as great leaps have been made recently. I have a huge debt of gratitude to curators and keepers of dress in museums who are totally unknown, but whose work we utterly rely on. I am inspired by the work of art historian Aby Warburg. I am working on a project about how various outmoded strands of iconography might be applied to exhibition-making and I always go back to him, somehow.

SC: Can you give us an idea of the process of preparing for a such a large-scale exhibition, like ‘The Vulgar: Fashion Redefined’ at the Barbican?

JC: This exhibition has indeed been rather over whelming in scale. For someone who prides herself on her architectural confidence the scale of it continues to take me by surprise. It helped that the definitions became the organising principles to the eleven subdivisions – making each section and selection manageable. Exhibitions then take on a life of their own, once the first loans come in there is a momentum. Because of the title of the exhibition, those first loans were hard to secure.

SC: You curated this exhibition with your partner psychoanalyst Adam Phillips – could you tell us about the collaborative process?

JC: Adam wrote the new definitions first, following more general conversations over a number of years. After working together on our Artangel project The Concise Dictionary of Dress in 2010, we assumed we would work together again – this time 11 definitions of one word as opposed to 11 installations, one per word. Adam is not familiar with most of the designers on display and this helps – it is not about who, therefore, but about how the work relates to the ideas.

SC: How do you think the presentation of fashion has changed in recent years?

JC: It has changed hugely. I am at the moment celebrating the anniversary of a project that was incredibly influential to me and that was the Florence Biennale of 1996. Twenty years ago is not that long ago!

SC: Could you tell us about some of your favourite or most memorable work experiences?

JC: This is all about individuals, that is what makes the experience. I am very lucky as I work with a number of practitioners who make it very pleasurable. In terms of a more general experience with an organisation it was certainly Artangel – their policy is to always privilege the work and the process over anything else, and it makes all the difference in the world.

SC: Are there any designers that you particularly enjoy collaborating with? And are there any you would hope to work with in the future?

JC: I think it is about overlapping preoccupations. I have worked with Hussein Chalayan for many years in different ways, maybe writing a text, a pubic conversation, a commission, it continues in different ways at different times. I value that a great deal. I have recently interviewed Christian Lacroix about his relationship to history for the show at the Barbican and that was something I had always wanted to do.

SC: Would you be able to tell us about any upcoming projects?

JC: I’m afraid I can’t. In the very near future I will be re-designing the Barbican show for the Winter Palace in Vienna which is thrilling.

SC: Would it be possible to give us an idea of what your day-to-day routine might comprise of?

JC: It is highly ritualised as it centres around our young children.

SC: Is there any creative field or type of output you are still keen to explore?

JC: Yes, embroidery. When I finish this project I am heading to the Lesage school where I started a course and had to interrupt it due to the pressures of work.

SC: What does London offer you as a curator and exhibition-maker?

JC: London offers a huge amount. I am not English, I was brought up in Rome of Australian parents so London was a choice not a given. I came here to study architecture and stayed. There are such diverse venues in London which are interested in engaging with the subject of fashion exhibiting that I have benefited as a freelance practitioner from this. I have been commissioned for example by Selfridges, by the V&A, for pop ups, there is a platform for conversations locally, the breadth of which is very rare.

SC: How does your academic profile compliment and allow to develop your exhibitions?

JC: I am offered sabbaticals all the time which I end up never taking as I love the combination of the two versions of my job: the academic – which is research (an incredible luxury) and teaching (another incredible luxury) – and exhibition-making. Having to articulate what you are doing all the time makes you formulate it more clearly in your mind. It also gives myself and my colleagues a sense of a Department in the old fashioned sense, where there were real ideological affinities.

SC: How did you get into this industry? What was your journey?

JC: I founded a gallery in 1997 dedicated to exhibiting fashion, the exhibiting bit was the subject. It was really specialised. I had seminars and small openings and slowly people came to see what I was doing and wrote about it. There was no blogging, no Instagram, so it was all word of mouth. The experts in the field were all associated to museums, so suddenly I found myself in a very particular role of being available for very disparate projects: helping install fashion in different museums, and eventually Linda Loppa invited me to curate a show at the newly built ModeMuseum. This was the shift, it was thanks to her. Suddenly I had to scale up the ideas that had underwritten the tiny shows in my gallery. I curated Spectres: When Fashion Turns Back, for her, which then travelled to the V&A and was seen by many more people.

SC: What is a piece of advice you would give someone interested in entering this field?

JC: Do our Masters Programme at LCF. (I am not entirely joking) Amy de la Haye and I put our hearts and souls into it.

SC: Which area in London do you principally work from? Why did you chose this area in particular?

JC: It varies, as sometimes I am working from London College of Fashion (Oxford Circus) and sometimes from home (West London) or from wherever the exhibition is situated – so I am entering a period of working from the Barbican.

SC: Favourite place to relax?

JC: Home.

SC: Favourite restaurant?

JC: Kam Tong on Queensway.

SC: Favourite holiday destination or where would you live if not London?

JC: Rome.

The Vulgar: Fashion Redefined at The Barbican Centre from 13 October 2016 to 5 February 2017

Interview by Tamara Akcay / Feature image by Hyea W Kang courtesy of Judith Clark