London’s Art Deco Icons

By Something CuratedThe term Art Deco, formally coined after the International Exhibition of Modern and Industrial Decorative Arts held in Paris in 1925, encompasses a decorative style of bold geometric shapes and bright colours, spanning furniture, textiles, ceramics and architecture. Deco, prevalent during the 1920s and 30s, was a pastiche of many different styles, sometimes contradictory, united by a desire to be modern. The aesthetic traversed across Europe to the United States and Britain, where it became a favourite for building types associated with the new age, such as airports, cinemas, swimming pools, office buildings, and department stores. There were overlaps with Modernism, with the use of clean lines and minimal decoration, but the style also lent itself well to buildings associated with entertainment, providing opulent interiors for hotels, restaurants and luxury living spaces.

What we celebrate today as Art Deco is truly eclectic, inspired by a breadth of international cultures. Cuban and Constructivist influences can be seen, as well as references to ancient archaeology, such as the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb in Egypt in 1922. Art Deco architecture also reflects the new industrial age and technology change, integrating sleek forms inspired by aviation, skyscrapers and radio sets. This made it a popular choice for London’s Underground stations, cinemas, theatres, factories and corporate headquarters. Something Curated rounds up the most awe-inspiring Art Deco buildings that call London home, taking a closer look at the architects responsible for them.

Adelaide House || Sir John Burnet & Thomas S. Tait

When it was completed in 1925, Adelaide House, located in London’s primary financial district, was the City’s tallest office block, at 43 meters. The building was named in honour of King William IV’s wife, who, in 1831, had performed the opening ceremony of London Bridge. Adelaide House was the first building in the City to employ the steel frame technique that was later widely adopted for skyscrapers around the world. Sir John Burnet and Thomas S. Tait designed the building in a discreet Art Deco style, with Egyptian influences, popular at the time after the recent discovery of Tutankhamen’s tomb. There used to be a fruit and flower garden and an 18-hole mini golf course on the roof. The building has been Grade II listed since 1972.

Carreras Cigarette Factory || Marcus Evelyn Collins, O.H. Collins & Arthur George Porri

The intriguing former factory was designed just four years after the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun, a find which made Egyptian style extremely popular among the Art Deco architects of the 1920s. The building was erected in 1926-28 by the Carreras Tobacco Company owned by the Russian-Jewish inventor and philanthropist Bernhard Baron on the communal garden area of Mornington Crescent, designed by architects Marcus Evelyn Collins, O.H. Collins & Arthur George Porri. Its distinctive Egyptian-style ornamentation originally included a solar disc to the Sun-god Ra, two gigantic effigies of black cats flanking the entrance and colourful painted details. When the factory was converted into offices in 1961 the Egyptian detailing was lost, but it was restored during a renovation in the late 1990s and replicas of the cats were placed outside the entrance.

Broadcasting House || Val Myer & Watson-Hart

Situated on Portland Place and Langham Place, Broadcasting House is the original headquarters of the BBC. The first radio broadcast was made there on 15 March 1932, and the building was officially opened two months later, on 15 May. The main structure is designed in an Art Deco style, with a facing of Portland stone over a steel frame. It is a Grade II listed building and includes the BBC Radio Theatre, where music and speech programmes are recorded in front of a studio audience. The site features a lobby that was used as a location for filming the 1998 BBC television series In the Red. Interestingly, architects Val Myer and Watson-Hart had begun working together from 1927 for the consortium headed by Lord Waring, who owned the sites that the BBC had identified as a potential location for their new headquarters.

Claridge’s Hotel || Oswald Milne & Basil Lonides

The renowned hotel dates back to the 19th century but an opulent makeover in the 1920s by the architect Basil Lonides has made the building synonymous with Art Deco. Claridge’s invited Lonides to re-design the restaurant and several suites. His magnificent engraved glass screens still adorn the restaurant today. By 1929 the hotel was a world-renowned showcase for leading British designers. Oswald Milne designed a new main entrance, removing the original carriage drive. A façade of Roman stone and jazz moderne mirrored foyer completed Claridge’s new look. In the early 1930s Milne added an extension to the east side of Claridge’s. With its simple cubic outline, the tall brick block stands in both contrast and harmony with the main hotel building. In the late 1990s, even more rooms, including the foyer and restaurant, were transformed into the Deco style.

Daily Express Building || Ellis and Clark, Robert Atkinson & Sir Owen Williams

The Daily Express Building was designed in 1932 by Ellis and Clark to serve as the home of the namesake newspaper and is one of the most prominent examples of Art Deco architecture in London. The exterior features a black façade with rounded corners in vitrolite and clear glass, with chromium strips. The extravagant lobby, designed by Robert Atkinson, includes plaster reliefs by Eric Aumonier, silver and gilt decorations, a magnificent silvered pendant lamp and an oval staircase. The furniture inside the building was, for the most part, designed by Betty Joel. As part of a redevelopment of the surrounding site the building was entirely refurbished in 2000 by John Robertson Architects. The foyer was recreated largely from old photographs and the façade completely upgraded.

Eltham Palace || Seely & Paget

In 1933, American couple Stephen and Virginia Courtauld acquired Eltham Palace, the derelict childhood home of Henry VIII. They set about restoring the remaining parts of the palace and created an elaborate home with sumptuous Art Deco interiors. Featuring an extravagant entrance hall, with a domed glass roof and curved wood-lined walls, the space is a unique example of the style. Architects Seely and Paget incorporated the great hall, the most substantial survival from the medieval royal palace, into the design. The Courtaulds’ home is now presented with a mixture of original and replica items of furniture and works of art. The interiors combine an eclectic amalgam of aesthetics. Typical features include wall surfaces lined with a range of native and exotic woods, the use of pale paint colours, and ceilings designed as an integral part of the room.

Hoover Building || Wallis, Gilbert & Partners

The property, owned by supermarket chain Tesco since the 1980’s, was formerly a factory for the Hoover Company, though it was also used to manufacture electrical equipment for planes and tanks during the Second World War. In 1931 the Ohio-based vacuum cleaner makers commissioned Wallis, Gilbert and Partners to create a factory on the Western Avenue in Perivale. Modern architectural commentators generally treat the Hoover factory as an art deco design, but architect Thomas Wallis amusingly termed his style as ‘Fancy’. The building’s ornamentation is said to have been inspired by Central and North American Indian architecture and art, though there are Egyptian influences present too.

Arnos Grove Underground Station || Charles Holden

Arnos Grove Underground Station opened in 1932 as the most northerly station on the first section of the Piccadilly line extension from Finsbury Park to Cockfosters. Described as a significant work of modern architecture, the unusual building was conceived by British architect Charles Holden, who designed many London Underground stations during the 1920s and 1930s. In 1971, the station became Grade II listed. In 2005, the space was refurbished with the heritage features carefully renovated. Notably, the station has gained somewhat of a reputation for its horticultural, having been awarded Best Overall Garden in the Underground in Bloom 2011 competition.

Florin Court || Guy Morgan & Partners

Acting as the home of Agatha Christie’s legendary detective Hercule Poirot in the television series from the 1990’s, Florin Court itself dates back to 1936. Built by Guy Morgan & Partners, who worked until 1927 for Edwin Lutyens, it features an impressive curved façade with projecting wings, a roof garden, setbacks on the ninth floor and a basement swimming pool. It is said to be one of the earliest of the residential apartment blocks in the wider Clerkenwell district, immediately north of the City of London. The walls were built in beige brick, made especially by Williamson Cliff and placed over a steel frame. Regalian properties refurbished the building in the late 1980s, to designs by Hildebrand & Clicker architects, providing today’s interior layout and further facilities.

Ideal House || Raymond Hood & Gordon Jeeves

Ideal House, today more commonly known as Palladium House, is a grade II listed Art Deco office building located on the corner of Great Marlborough Street and Argyll Street. The striking building was constructed in the late 1920s as the headquarters of the American National Radiator Company. Black and gold were the livery of the firm, explaining the unusual and extravagant colour scheme. Built between 1928-9, the building was designed by architects Raymond Hood and Gordon Jeeves in the Art Deco style, comprising a seven story office block, with black granite facing decorated with an inlaid champlevé design, inspired by traditional Egyptian art.

Apollo Victoria Theatre || Ernest Walmsley

Apollo Victoria is one of London’s most impressive examples of an Art Deco theatre. Constructed in 1929, the structure is built mainly from concrete. Inside, there is a nautical theme, featuring columns that appear to burst into fountains and shell motifs. Designed by architect Ernest Walmsley, the theatre follows the Art Deco style that is now ornamented to reflect the glittering Emerald City. Upon its official opening in 1930, the Gaumont British News charmingly called the theatre interior “a fairy cavern under the sea, or a mermaid’s dream of heaven.” Known as the New Victoria Cinema, the building was renowned as a place to watch film, big band and variety performances, all within walking distance of Victoria station.

Savoy Hotel || Stanley Hall Easton & Robertson

The Savoy set new standards for technology, comfort, and luxury, often described as the first true luxury hotel in London. First to be lit by electricity, The Savoy was also the first to feature electric lifts, known as ascending rooms. Guestrooms were connected by speaking tubes to various parts of the hotel, including the valet, maid, and floor waiter. During the 1920s The Savoy embraced the Art Deco movement enthusiastically: Art Deco décor and furniture was installed in the hotel, Kaspar the Savoy’s lucky black cat was carved by designer Basil Ionides in 1927, and the iconic stainless steel Savoy sign over Savoy Court, designed by Sir Howard Robertson, was installed in 1929.

Oxo Tower || Albert Moore

The tower was largely rebuilt to an Art Deco design by architect Albert Moore between 1928 and 1929. Much of the original power station was demolished, but the river-facing facade was retained and extended. Liebig wanted to include a tower featuring illuminated signs advertising the name of their product. When permission for the advertisements was refused, the tower was built with four sets of three vertically-aligned windows, each of which “coincidentally” happened to be in the shapes of a circle, a cross and a circle. This was significant because Skyline advertising at the time was banned along Southbank. Today, the building has mixed use as Oxo Tower Wharf containing a set of design, arts and crafts shops on the ground and first floors with two galleries, as well as the OXO Tower Restaurant, Bar and Brasserie on the eighth floor.

Royal Institute of British Architects || George Grey Wornum

66 Portland Place was designed by architect George Grey Wornum. He was the winner of a competition to design the new headquarters for the RIBA, which attracted submissions from 284 entrants. Building work commenced in mid-1933 and completed in time for the organisation’s 100th anniversary. At a time of heated debate about what architectural style should be used and during an economic downturn, Wornum’s building opened on time and on a reduced budget. He worked with a range of artists and craftsmen, such as Edward Bainbridge Copnall, James Woodford, Jan Juta, Denis Dunlop and Raymond McGrath, to create the decoration in the interiors and on the façade. Many of these details carry symbolic significance, for example, on the fourth floor are six glass panels representing the great periods of architecture.

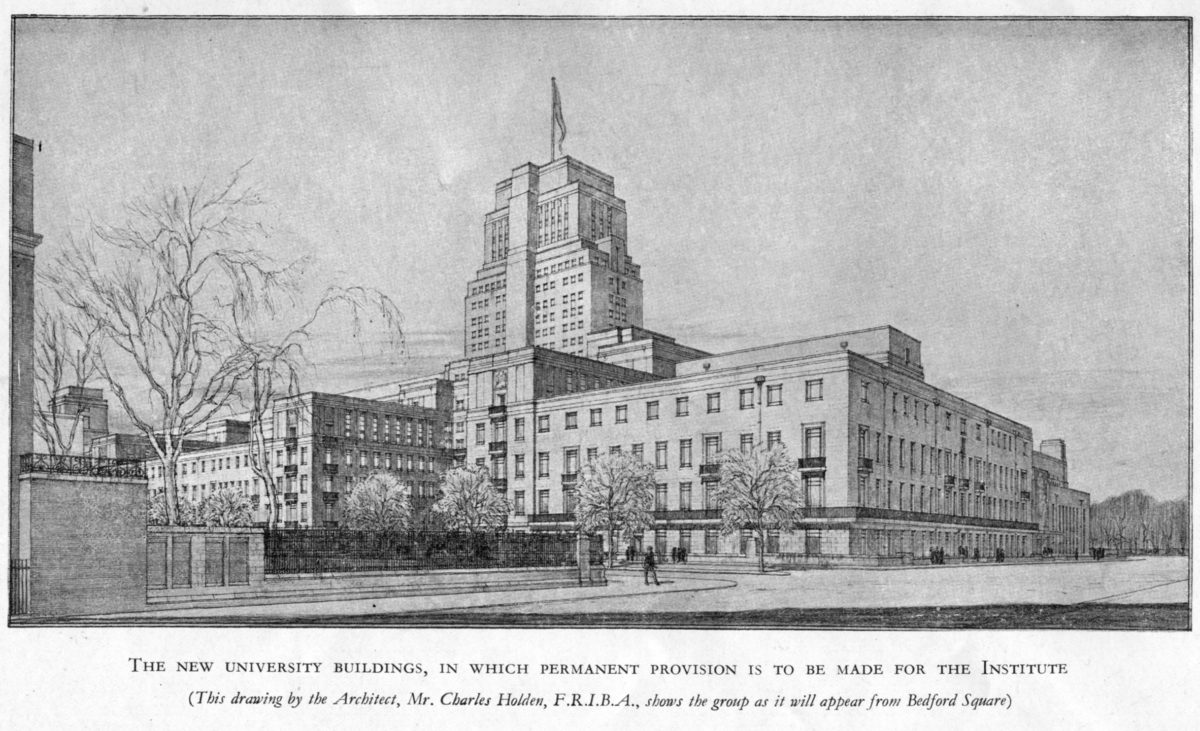

Senate House || Charles Holden

Senate House is the administrative centre of the University of London, situated in the heart of Bloomsbury. The Art Deco building was constructed between 1932 and 1937 as the first phase of a large uncompleted scheme designed for the University by Charles Holden. Holden’s original plan for the building was for a single structure covering the whole site, stretching almost 370 meters from Montague Place to Torrington Street. It comprised a central spine linked by a series of wings to the perimeter façade and enclosing a number of courtyards. Construction began in 1932 but due to a lack of funds, the full design was gradually cut back. The completion of the buildings for the Institute of Education and the School of Oriental Studies followed, but the onset of the Second World War ultimately prevented further progress.

Shell Mex House || Messrs Joseph

Shell Mex House was built between 1930 and 1931 on the site of the Hotel Cecil and stands behind the original facade of the Hotel and between the Adelphi and the Savoy. Broadly Art Deco in style, it was designed by Ernest Joseph of the architectural firm of Messrs Joseph. Its most prominent feature is its central tower which houses a large clock with faces looking towards the river and the Strand. The entrance of the building, which is through an impressive gated archway, features a green plaque affixed to the wall, proclaiming: “The Royal Air Force was formed and had its first headquarters here in the former Hotel Cecil 1 April 1918.” During the Second World War, the building became home to the Ministry of Supply which co-ordinated allocation of equipment to the national armed forces.