The Barbican Centre Celebrates The Extraordinary Career Of Composer Philip Glass

By Something CuratedThe world famous composer Philip Glass celebrated his 80th birthday this week. To mark the occasion, throughout 2017 the Barbican Centre is holding a series of concerts showcasing the full breadth of his career, including a performance of his seminal piece Music in Twelve Parts.

One of the founding figures of the musical style known as Minimalism, Glass has written over 11 symphonies, 14 operas and countless film scores. Yet, despite a prolific career that spans over five decades, the composer shows no signs of letting up. Earlier in the week his expansive repertoire was honoured with an entire day of performances from the BBC Symphony Orchestra, while tickets for his upcoming collaboration with Laurie Anderson this May sold out in just a few short hours.

In the run up to the Barbican’s season of concerts celebrating American contemporary composers Reich, Glass, Adams: the Sounds that Change America, we look at how this modest, mild-mannered figure became one of the towering figures of 20th century music.

Born in 1937, Glass was surrounded by music from a young age. The son of Jewish Lithuanian immigrants, his mother was a librarian while his father owned a record store in his hometown of Baltimore, Maryland. In a time before unlimited streaming and file sharing, this gave Glass unparalleled access to the latest recordings alongside entire canons of classical music.

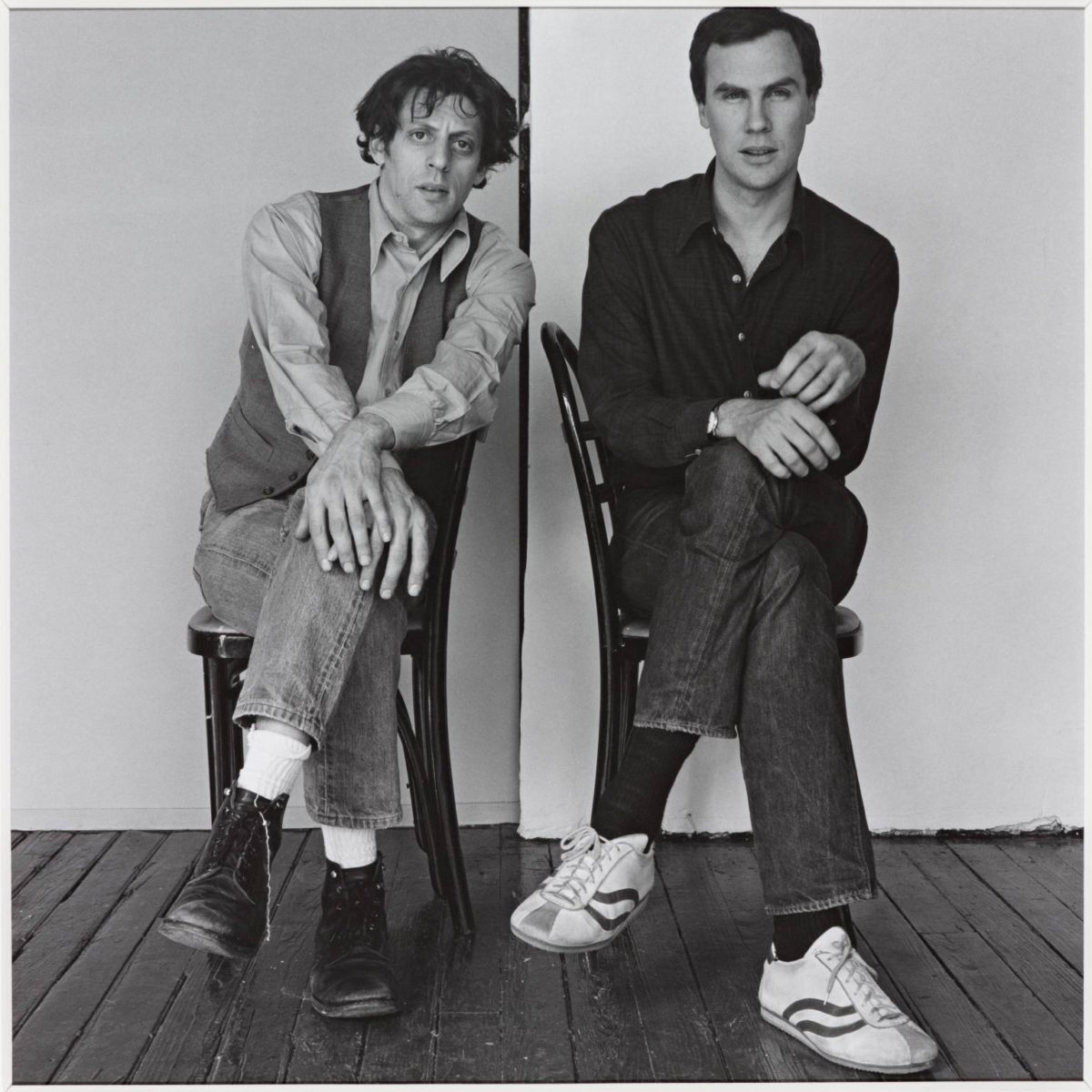

A bright child who excelled at playing the flute, at just 15 Glass left home to study mathematics and philosophy at the University of Chicago. His aptitude for music was rewarded by a scholarship to the Juilliard School of Music in Manhattan (with fellow minimalist icon Steve Reich) and a move to Paris in 1964 under the mentorship of renowned teacher Nadia Boulanger. Stints as a musical director for experimental theatre companies followed as well as work on a film score for virtuoso sitar player Ravi Shankar – experiences that would inform later compositions for the stage and screen.

In 1967, Glass headed back to New York to immerse himself in the SoHo arts scene forming the Philip Glass ensemble a year later. Still a central part of Glass’s company to this day, the ensemble showcased his new, minimal approach to composition through the then unconventional combination of woodwinds, keyboard and solo voice. However, due to the amplified nature of these performances, Glass found himself increasingly shunned by the concert world and forced to play to more creative crowds in the cities underground venues.

With American audiences not quite ready for his contemporary classical style and desperately in need of cash to support his young family, throughout the 1970s Glass was forced to work nights as a taxi driver. Starved of government funding, New York was a city on the brink of collapse with the threat of crime around every corner. Yet despite the perilous shifts, Glass was not swayed from his ultimate goal of composing as he explained in the BBC Radio 4 documentary Philip Glass Taxi Driver (2015): “In those days when I was writing Einstein on the beach I’d be writing music until about six in the morning. Then it was time to take my kids to school and then I would go to sleep until around three and at three I’d go back to the garage.”

It was during this time that he composed some of his most ground-breaking pieces including Music in Twelve Parts (1974) and the aforementioned Einstein on the Beach (1976), both of which premiered at the New York Town Hall paid for by Glass using the money from his day job. An abstract opera that featured no concrete narrative, it was Einstein that ensured Glass could quit driving around the seven boroughs and concentrate on composing full time. Having conquered the concert halls that had once turned their noses at his minimal music, Glass once again went against the grain by releasing Glassworks (1982), a hugely successful attempt to create a more pop-oriented sound, as well as working on a series of film scores beginning with North Star (1977).

What’s most striking about Glass’s move into film music is how little he had to compromise or alter his trademark sound to fit the medium. The literal heart beat part of each piece, it’s impossible to imagine these features without Glass’s soundtrack – the repetitive motifs and driving rhythms marrying perfectly with the shots on screen. Take for example his score for Errol Morris’s crime documentary The Thin Blue Line (1985), in which Glass’s score almost mimics the re-enactment of a single scene from multiple angles. These were the first in a long line of film soundtracks including such Hollywood blockbusters as Candyman (1992), The Truman Show (1998) and The Hours (2002), winning him yet more accolades and showcasing his work to an even broader audience.

It is this ability to appeal to countless tastes and generations that makes Glass’s work so unique. He has collaborated with countless cultural icons including Allen Ginsberg, David Bowie and Laurie Anderson, with whom he reunites this May to perform their piece American Style (2015) at the Barbican Centre.

Words by Dale Marshall