Interview: Ben Murphy, Photographer

By Something CuratedLondon-based photographer Ben Murphy works all over the world, and has exhibited his images at the Courtauld and Architectural Association galleries among others. Notably, he has work in the permanent collections of the V&A and the National Portrait Gallery. Murphy has utilised the aesthetic potential of photography to create an impressive body of work as a cultural geographer. Through his photographs, he presents the various ways in which space can become meaningful and representational as place through human interaction. Though he classes much of his photography as portraiture, his subjects are often unsettlingly absent from the frame; it is in the architecture and detritus of a place through which identity is uncovered in his work.

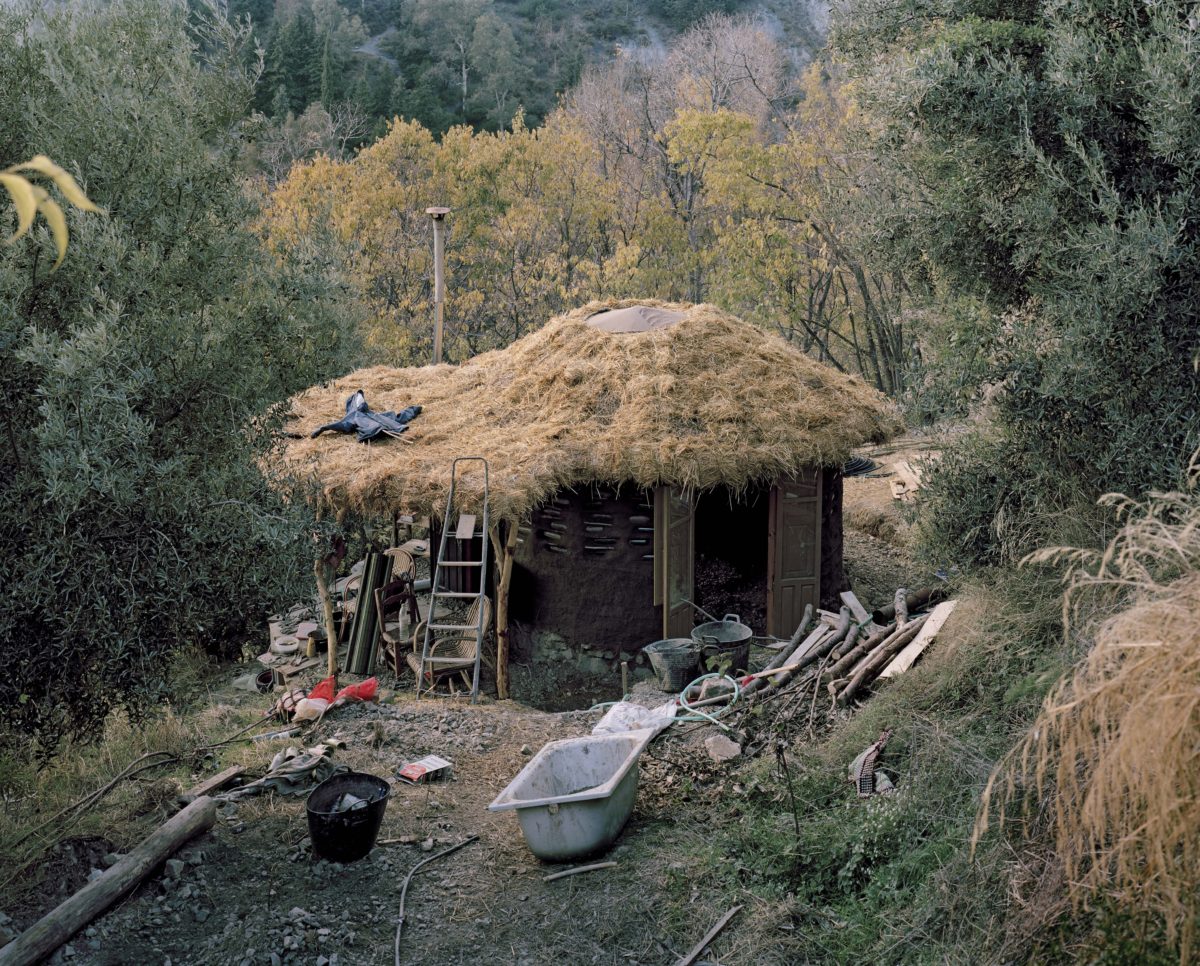

In his latest exhibition, ‘Riverbed’, running at the Architectural Association Gallery from March, Ben has captured the temporary, makeshift homes and vehicles inhabited by groups of neo-nomadic countercultures in Andalucia, Spain. These settlers include a strongly British contingency coming from hippy, punk, post-punk, rave, and ‘New Age Traveller’ backgrounds, ostracised in the 80s by Thatcher and the Criminal Justice Act. The scrapheap design of their living spaces appears defiant towards the mainstream, even parodic; these anti-establishment non-conformist communities are, very self-consciously, migrants by choice. Strikingly, Ben places the home at the centre of the image, as if somehow rooting the identity of the individual dweller in their very rootlessness.

Their sites run along dried-up riverbeds, in ravines, and off mountain passes, often actively inhospitable environments. They are historically sites of rebellion, located on land fought over by the Moors and the Christians, as well as the fascists and communist rebels during the Spanish Civil War. To some, this is utopia. Ben talks to Something Curated about the gap between ideals and reality, and the inherent paradoxes and difficulties faced when trying to live self-sufficiently outside of the mainstream.

Something Curated: How did you come about working on this series?

Ben Murphy: I read a book by T.C. Boyle called Drop City which fired my imagination. It described a dysfunctional hippy community in America in the late 60s. I subsequently found out that there was a real community of the same name which imploded, ending in power struggles and mayhem. That was really the catalyst for the work. Then I happened to be talking to a friend at a party who said that she knew somewhere similar operating now in Spain. She introduced me to a guy living there and I eventually persuaded him that I wasn’t going to expose where they were and I wasn’t a journalist; I was just coming at it from an artistic perspective. I arrived there for the first time and was immediately struck by this Mad Max-type scenario on a dried-up riverbed, hence the title of the work.

SC: Can you tell us a bit more about ‘Riverbed’ and the vision behind it?

BM: It’s hard to say that I had a vision; I had an inquisitiveness and when I got there I just reacted to what I found. I have been interested in counterculture, green politics, and alternative ways of living since I was thirteen. I come from a history of involvement with punk, post-punk and New Wave music and I have a cynicism towards authority.

When I started, I was quite intimidated by the site. It was chaotic and anarchistic and the dwelling spaces were deliberately confrontational and rejectionist. I was interested in their subversions of standardised forms of acceptable living. So, the idea of living in a truck which was originally designed to put horses in, or an ordinary caravan which is no longer ordinary because it’s taken out of the context of how it was intended to be used. There’s one picture and, if you look closely, there’s a television set which has a tableaux in it of things from old British TV, and there’s a dog mounting another dog. That is an uncomfortable image, but it’s subversive. The TV set is there, but it has been subverted and made undoubtedly disquieting.

Another interest in my work is: how do the counterculture identities maintain themselves – how do they keep representing themselves and renegotiating their identities – given that those identities came out of political unrest in the UK, for instance, or another catalyst? How do they then transpose that identity into a foreign country? And I wanted to find out if there were distinct types of tribal identities being expressed in different forms of dwelling, or whether there was a homogenisation of countercultural identities, or a hybrid identity.

SC: Are you suggesting that it’s through the very fact of their dwelling there and the situation of their living that they are reasserting their identity?

BM: Yes, the dwelling is integral to their identity – as it is to everyone. Home is very important to our identity.

SC: Were the people you met quite open to talking about their non-conformity?

BM: Some of them were. Some of them were quite guarded. They are there for a reason. Where they are is deliberately inaccessible. So, that sets them apart and says that these people do not want to communicate. For me to walk into that was problematic. I’m conspicuous. I have a large format camera. I’m there – I’m being noticed. Having said that, there are some people who are happy to talk and think it’s important that their lifestyle choices are publicised. Other people say, “go away.” I was threatened with a rock. Another man had an axe and said, “you don’t belong here, you don’t know what it’s like to be here,” saying I’m a voyeur, which is sort of true.

SC: Was the fact that there was some discomfort with you photographing the area part of the reason why you chose to leave the subjects out, the people?

BM: No – it was a gradual realisation that it completely shifts the nature of the work if you have people in there. It’s too direct, too obvious, too documentary. I want viewers to put themselves in the picture, which is what happens when you take people out and you start seeing things which you would otherwise overlook. Mundane objects become present and significant because of the stillness of the photograph. And, in a way, my process, using a large format camera, enables fine detail to be drawn out and observed and reflected on. It’s not to do with keeping them anonymous – some people were happy to be photographed – but the strength of it came through taking them out. Let’s just look at identity and how it’s represented through absence, through the stuff that’s left behind.

SC: Why did you look at these sites in particular? Is it part of a wider movement across Europe?

BM: I went to this area not for any other reason than I was told about it. I know that there are other places in Spain, in Portugal, France, and in many Western cultures there are collectives of people trying to live off the grid. Some are successful and some aren’t. It’s almost inevitable that, in trying to live outside society, you have to in some way involve yourself in the society you’re trying to reject. There’s all sorts of baggage that you can’t help but bring with you, e.g. codes of conduct for what’s acceptable and what isn’t acceptable.

It is reliant. It is not self-sufficient, and they would admit to this. Some of them send their children to the local schools. They use the roads. They use cars. They buy stuff in the supermarkets. They are not operating as a cohesive community. They are individuals who happen to be in the same area who share similar views about rejecting the mainstream. But they are dependent on it. They wouldn’t be there and they can’t survive without the support of the mainstream.

SC: Explain your reasoning behind not titling the images, except for the name?

BM: I don’t really like the idea of making titles because then you are telling people what to think but, for instance, the dwelling Crusty Mark. I couldn’t not have Crusty Mark in the title.

SC: Did he introduce himself as Crusty Mark?

BM: No, he was just known as Crusty Mark. The other thing is that most of these people aren’t there the next time I go. I am fascinated by what photography does in that in the moment you’ve taken the image it can’t help but be history. I like the idea of how this relates to their transience. The image is a record of something that doesn’t exist. So, Crusty Mark, for example, isn’t there anymore. Some places actually get re-inhabited, and there’s a continual flow of people going through the same dwelling space.

SC: Did you envy them?

BM: I do have a strange fantasy about escaping and I guess that’s the reason why I’ve done the work. I don’t envy but I do like the idea. But the reality of it is very difficult. It’s a dried up riverbed. It’s infertile. It floods every ten years. There’s a reason why the Spanish people don’t live there. There’s just rocks and it’s not an easy lifestyle.

Philosopher Nigel Warburton talks about paradise in his essay on my work in the photography journal ‘Portfolio’, and that came through me having a conversation with one of the people who said “this is paradise”. I was thinking it’s quite hard work for paradise, especially after the tracks were made in accessible by the local authorities. So, they have to get all their stuff brought in on foot or by donkeys. They have gas bottles. But it’s 5 kilometres from the nearest small town. They have no electricity, so they have batteries and solar panels that sometimes work and sometimes don’t. It’s a really hard life.

SC: How does this relate to other projects you have worked on?

BM: I photographed the United Nations building in New York – which is seemingly very disparate to this – but it’s essentially coming from the same idea in my head about how space is affected by people’s inhabitations and reactions. Also, I did a comparative study halfway through my work in Spain. I won an award from the Graham Foundation of Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts, Chicago to make a study of American homeless people’s encampments. Again, they are peopleless images, and the dwelling spaces look fairly similar to some of these, but there is a huge difference in the people. The people in America had been rejected by society and were trying to get back into it. That work was about homelessness as a representation of identity. It was looking at the dysfunctionality of American society to allow that to happen. It’s the absolute antithesis of the riverbed culture which has decided to remove themselves – attempt to remove themselves – from society.

SC: Is it almost more of a dysfunction with society that people might choose the dwelling spaces that other people are forced into?

BM: Well, one of the things that I want from the series is for people to reflect on their own set of judgements and values on how we all live and what is the perfect way of living and what we aspire to. It might not function quite perfectly in the counterculture, but they are still justified in attempting to live outside. And who can blame them for that?

SC: What does London offer you as a photographer?

BM: I am sure I wouldn’t have been taking the photographs I do if I didn’t live here. My career as a photographer has been greatly affected by being here; being offered great work from magazines, photographing interesting people and being commissioned to do work all over the world all stems from being here. But it’s also an incredibly stimulating and rewarding place for art and culture and that ultimately feeds into one’s work.

SC: What was the last photograph you took?

BM: I’ve been commissioned by National Grid to photograph the most significant gas holders across the UK for a historic archive before the majority are dismantled. Yesterday I was on top of the somewhat unstable convex cast iron domed roof of a gasholder in Bethnal Green, east London, photographing another gas holder’s exo skeletal frame on the same site. I had to tread very cautiously because underneath this thin rusted metal skin was a 50 metre drop. I have become obsessed with getting perfect symmetry. The more I work on these, the more I recognise their inadvertent beauty and their industrial, architectural, historical and cultural significance. I feel very much in the shadows of the great German photographers Bernd and Hilla Becher, who photographed seemingly mundane industrial buildings, including gas holders, for thirty years or so up to the 1980s, always with the same approach, always large format black and white, devoid of people, diffused light. Their works are usually seen in series as typologies and transcend document, working on many levels of interpretation. I really love their work. I like to work in diffused light, and I am photographing a subject they also photographed but that’s probably where the similarity ends. These pictures can’t help but be historic document, but will be reflections on a different urban landscape at a different time.

SC: Favourite photographers?

BM: I’ve already mentioned the Bechers, however there are many photographers whose work I admire; here are a few, some from the C19th and C20th and some contemporary: Felice Beato, William Christenberry, EH Engstromm, Walker Evans, Peter Fraser, Stephen Gill, Candida Hofer, August Sander, Nigel Shaffran, Thomas Struth, Diasuke Yakota. There has been an increasing number of photographers like Stephen Gill and Diasuke Yakota who are challenging the enforced conformity of digital photography and experimenting with analogue and digital processes and I think this is an interesting development, pushing the boundaries and notions of what photography is and can be.

SC: What is a piece of advice you would offer aspiring photographers?

BM: Photographers have different ways of working, different interests, objectives and concerns. However, to produce really good work there has to be a conviction and commitment to making a picture, as with making anything worthwhile. The best photographs in my opinion come from really looking very hard at what is presented to you before making the photograph. As well as understanding your motive for making the work, whatever that might be, there has to be a consideration of the subject, the composition, colour and light. You must also think carefully about what it is you are trying to achieve as the final image, because that is affected profoundly by the equipment you use and the processes involved. Always be respectful.

SC: Whereabouts in London do you live and what is your favourite aspect of living there?

BM: I live in an area of south east London called Herne Hill. It is less populated than much of London because it is very near Dulwich which has lots of green spaces and has a village like atmosphere. Here, it is close to the centre of London, but it is also relatively quiet and relaxed. Coming from the Peak District in Derbyshire I miss the sense of big open space and the hills. As well as having the brilliant Dulwich Picture Gallery locally, it is so easy to get to any part of town. Although London is a frustrating and expensive place to live in many ways, I love the incredible culture this city has to offer: exhibitions, dance, theatre, film, music and living here gives me access to all this.

SC: What is your favourite gallery in London?

BM: That depends on the exhibition being shown at any one time, however, if I had to choose one it would be the National Gallery.

SC: Favourite restaurant?

BM: I’m vegetarian and there is a great vegetarian restaurant called Mildreds on Lexington Street in Soho. It has been going for years. It has a great, friendly, lively, unpretentious atmosphere and serves excellent inexpensive modern vegetarian and vegan food. I also love Maison Berteaux on Greek Street, W1. It is a fantastically eccentric and authentic French patisserie, owned by my friends the Wade sisters. Wonderful cakes, charming staff and always interesting people in there.

SC: Favourite holiday destination?

BM: That’s a big question. I’m not sure I could choose a favourite place for a holiday. I love to travel either for work or pleasure. I find inspiration in foreign unfamiliar places even if I’m on my own and lonely, for example, in China or Sri Lanka where I have been to make work. In the winter I go with my family to Cornwall. I like the wildness of the sea and the landscape there. In the summer I hanker for the warmth of the Mediterranean. My ideal holiday would be to spend a month in a beautifully run down stylish old hotel in Africa or India or the Mediterranean with a pool and a verandah, and waiters in white tail coat jackets serving drinks at sundown, with a pianist and band playing gently in the background, and a mix of bohemian guests with whom I could talk nonsense and relax. Can anyone point me in the right direction?

SC: Where would you live if not London?

BM: In a grand decaying Georgian house in Dorset, an apartment in New York, and a minimalist modern house somewhere on the Mediterranean. That’s not asking too much is it?

Interview by Ella Bucknall | Images courtesy of Ben Murphy