Interview: Rory Parnell-Mooney, Menswear Designer

By Something CuratedOn the bookshelves, seminal texts by writers including James Baldwin and Garth Greenwell sit beside books on fashion history and pattern cutting, as well as a selection of intriguing handmade pots, crafted by the designer. Religion, protest, queer culture and youth: these are some of the critical themes that run through Irish-born London-based menswear designer Rory Parnell-Mooney’s work. He showed his graduate collection at London Fashion Week in 2014, after completing a Masters in Menswear at Central Saint Martins. He then presented his work at London Collections Men in January 2015 with support from Fashion East, followed by a second solo collection, shown at the 10th anniversary of the MAN show at LCM. Notably, he has worked with influential retailers including Dover Street Market London and New York, as well as H. Lorenzo, LA, and Nowhere, Dublin. Something Curated caught up with Parnell-Mooney at his east London studio to learn more about his label, the ritualistic art of dressing, and his favourite spots in the city.

Something Curated: Broadly speaking, could you tell us about the vision and ethos behind your label?

Rory Parnell-Mooney: With every garment I send out, the basic things I want to do are to make it simpler and better. Like, if you take a hoodie, I want to play around with it, but also keep what it is, just removing all the unnecessary bits. That’s what I’ve done in every collection. I put the clothes on and go, “Okay, I don’t like that bit, that’s what I’m going to change.” If I put it on and it feels weird, then it doesn’t go in. It’s about problems I have with other clothes and trying to solve them and that’s what good design should be about – solving problems. Simple, clean and to the point is it. In fact, my partner Jack once said that every collection that I’ve done is as direct as a curse word. It gets the point across. There isn’t any faff.

In regards to taking things out that I don’t like, it happens every day when I put on clothes. I question why people have designed clothes the way they have all the time. When I try a shirt on in a shop, I think, “Who’s the moron who designed it like this?” This is why I don’t want to buy clothes. I genuinely can’t remember the last time I bought an actual full priced piece of clothing. I buy all my clothes on eBay or at charity shops.

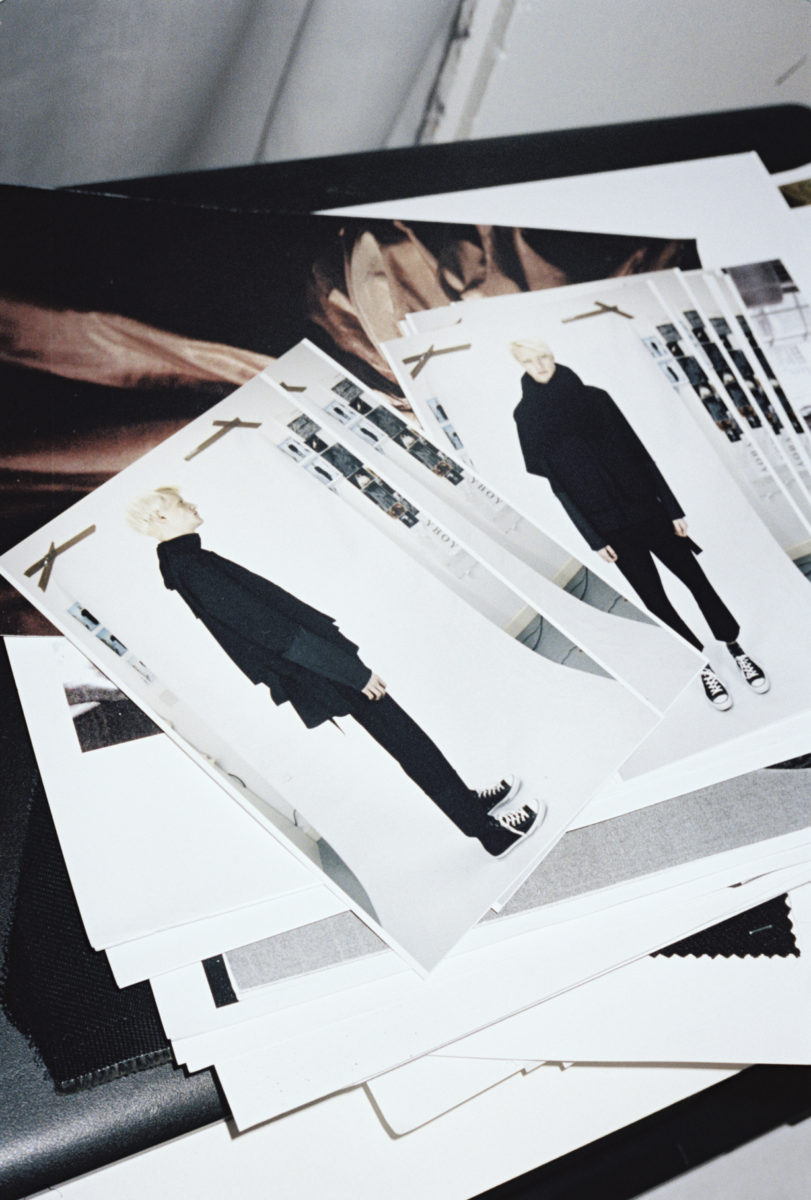

The way I’ve always designed collections is through fittings. Constantly having a model come in and fitting it on a body, you get to see why something doesn’t work. I know a lot of designers who just send things to factories and that’s it. There’s a real lack of interaction with the body. People forget when they’re designing collections that these are things made for people to actually wear. Not just to walk up and down a catwalk.

SC: What are you working on at the moment?

RPM: I was designing a collection before Christmas and was going to present it for Autumn/Winter, but ultimately didn’t like the collection and didn’t want to show something I wasn’t happy with. So we’ve decided to take a season off and really think about what it is I’m doing and what I’m putting out into the world. I don’t want to look back through my collections and think, “Wow, I really messed that up.” And I think a lot of designers do this, especially big places. Some collections shouldn’t have been shown.

I look back on my past collections and there were some garments that I didn’t like, but that’s all part of the process. But as the collections go, I genuinely really love my first season. The second was a weird one because I was in a weird place and I had a lot less time. But the music and the casting and the knitwear in the second show, the way of playing with fabric and pleating, it was great. The soundtrack was unbelievable for that second show. The finale music was Antichrist Superstar by Marylyn Manson. So good.

SC: What influences inform your work?

RPM: From the MA, I was looking at that juxtaposition between religious clothing and how people in religion cover their bodies, in comparison to people in protest. That juxtaposition between covering for religious reasons – to hide your body – to the opposite feeling of hiding your body from an authority. The next season moved on from those ideas of being seen and not being seen to religious clothing and boys on the street.

But there are themes I always want to play with, themes that always influence me, like youth and ecclesiastical things. If you ask me where it comes from, I genuinely don’t know. People say is it because your Irish. I’m not sure about that. I went to a Catholic school and it was really liberal. It wasn’t forced down my throat. But youth is so hard to describe but the religious side has always been of interest to me. I wouldn’t describe myself as religious. I don’t believe in a specific god. But I do talk of spirituality, but don’t say I’m this or that. Do I believe in certain things? 100%. I don’t think there was anything in my life that forced me to be obsessed with religion. If I was to go back to university now, I’d really want to study religious studies and maybe foreign languages.

Maybe it is about growing up in Ireland. Religion is more apparent there. There are churches everywhere and people actually go. Way more than London. And often in Ireland, the churches are open 12 hours a day. There’s nobody in there, but you can just go in. It’s different to here and you’re constantly surrounded by religion, maybe without even realising it is influencing you.

SC: Talking of religion and ritual, in your graduate collection, from 2014, you explored the ritual of dressing – could you tell us what this process means to you and what interests you in it?

RPM: Great soundbite that, the ritual art of dressing. I think it comes from what we were talking about, the whole ecclesiastical thing. I’ve exhausted every movie about nuns. There’s a beauty in the process of how people in religious institutions get dressed. It’s the nicest thing in the whole world to see. Actually, maybe it is a bit weird when you see altar boys dress priests. But look at when nuns dress each other. There are so many things that go into it. There are like eight different layers and the way they put them on is done in a ritualistic, ceremonial way. Across my whole collection, there are perfect little ties and there’s something beautiful in reaching behind yourself and tying it up. Tying something onto your wrists too, or something on the garment that is specific to you and you have to put it on like a little ritual.

SC: Is this exploration of ritual continued in your latest collection?

RPM: Yeah, I think it’s in every collection and will always be. When I put clothes on, I want to move them around. It’s how you get comfortable in what you’re wearing. When there is a tie or a cuff that has something specific on it, there’s an engagement with your body and the garment.

SC: What’s the most important thing you use in the studio?

RPM: Uh, my brain. But yeah, I don’t know. I suppose it’s me. I could work anywhere. I don’t need anything high-tech to do what I do. I just scribble on bits of paper. I think it’s weird when designers need fancy boards to draw on. I could work happily from a table.

SC: In your SS17 collection, there are wall-hangings and words stitched into the clothing. What inspired this? And how has your label changed since the MA?

RPM: The MA collection was very much about how far I could push it, like how weird it could get. I didn’t think how people were going to wear it. But gradually, it’s moved on and on to the point where I, personally, wear more colour and wear fancier stuff, stuff I wouldn’t have normally put on because two years ago I literally lived in a black hoodie and a pair of jeans that genuinely had an elasticated waist on them. In the past year, I’ve made a concerted effort to dress nicer and that shows in Spring/Summer.

But I think Spring/Summer was a funny season because I started it with Harriet Middleton-Baker and we kind of worked on the ideas together. She was working on the wall hangings and I was working on the collection and we brought them together at the end. So, the stuff about the woman as a god and loads of stuff about currency was done in a really literal way on the wall-hangings, and then in the collection we had to bring in these really female elements into the clothes. We used two girls in the show. It became more conceptual than other seasons, which were more product-driven.

SC: Berlin also seems significant in your work; in SS17, the red, white and black colour palette is striking. What about the city interests you in particular?

RPM: My intern, Justin, and I worked together and he was like an assistant designer on that collection. He had just got back from Berlin and I’ve been there loads of times and we talked about it a lot. We spoke about Berlin as the one place in Europe where there’s this free, sexual awakening that just doesn’t exist here. My partner Jack was talking to the filmmaker/photographer Matt Lambert who lives in Berlin and he said, “It’s just nothing like London.” He shoots these naked people and they’re more than happy to have sex as he does it. It’s not just about sexual exploration but they just don’t care. They don’t say you’re a girl, you’re a boy, so you have to wear this and you have to wear that. Maybe it’s not as free here because we have to work crazy hours, you know? There’s a real freedom there. And that’s what we wanted to put in the collection, about not putting things into little boxes.

SC: When looking at your collections there is clear reference to queer culture. How significant is queerness in your work?

RPM: That’s a big thing. Previously, Jack and I made a book where we pulled important parts from queer texts, but also things about the woman, and how I personally think gay people and females have a really strong connection. There was stuff about the moon, and about gods across different religions that have demonised women. There’s something amazing about looking at ancient religions where the woman is powerful, for example, where the moon is a female figure. It was this and the idea of queer identity all brought together.

And again, in Berlin, queer identity is such a massive thing but not in the same way as in America where they say queer studies and they’re bashing the queer drum. In Berlin, they don’t do that because they don’t need to. That’s the collection, looking at these young queer kids living openly. We wanted it to be completely open. We started using reds and green. We really wanted to use colour and use it well in this collection. I wish there was more green in it, but we ran out of that fabric. I was in a happier space too.

SC: Did you feel in the earlier collections you couldn’t do things exactly as you wanted?

RPM: My first three shows were with Fashion East and I was paid for it. It’s a different thing. But after, I wanted to do things smaller. But Fashion East helped me grow as a designer. It opened a lot of doors. Of course, they helped me do everything I’ve done and I’ve really got mad respect for Lulu Kennedy and Tash.

SC: What are you finding is the most challenging thing about setting up your own label?

RPM: I do think I did shows too soon. I wished I’d done a couple of seasons and gone to Paris and learned. I learned how to do sale and work in a showroom after a show and then selling to Dover Street Market, you know. I literally had to make up how to do an order sheet and I’d send it over and they’d send it back and say that it didn’t have this or this or this and I felt embarrassed. I wish I’d spent a year doing some small collections, gone to Paris and met people. Because now, the position I’m in, it’s taken much longer to build that sort of stuff up.

SC: Are there any designers in the industry that you especially admire?

RPM: Rick, Raf and Rei. Rick Owens because he’s amazing and he wasn’t strictly a designer. He was a pattern cutter. He doesn’t have a fancy degree. He’s a kid from LA and worked in a copy shop and copied patterns from really expensive coats and brought them back to the store and made knock-offs. He just has this incredible aesthetic, that has driven everything he’s done. Some of the collections are genuinely really cool and he actually cares about stuff outside of fashion – art, the people he works with, the factories, the fabrics. Raf, again because he’s amazing. He changed fashion. At Dior, for the first five seasons, is some of the best fashion we’ve seen in such a long time. And of course there’s his own brand that’s been going for 20 years. The first 10 years of his own label were mind-blowingly good.

Rei Kawakubo because she started Comme des Garçons in the 80s and made people care about fashion. I mean, okay, people did care, but it was never about a designer, it was always about a house like Dior or whatever. But with Rei, she brought talented people from Japan, she started working with concept too which is so nice. She came out and was like, we’re going to make everything out of plaster, then grow flowers out of someone’s ears and people were like this is great. She’s a genius. She’s a businesswoman. In terms of my contemporaries, there’s Liam Hodges. He’s great. And great at business and is very good at what he’s doing. Matthew Miller too.

SC: Having relatively recently graduated, what is a piece of advice you would give to those currently studying fashion?

RPM: Work. Don’t go to university. It’s going to cost you, what, £30,000 and then an MA will cost £20,000 and you’ll graduate with loads of debt and then you’re not going to get a job. Go and intern with someone for six months. Do it for free. Get a loan from your parents, that they were going to pay on fees, and go and work, work for someone. Just go and work. You’ll understand in the first six months whether you want to do this or not.

SC: Preferred work attire?

RPM: I think in the last year I’ve made more of an effort. If you dress more fabulously, you do work a bit better. I’ve been dressing up a bit more but it’s always black, you know, fashion uniform, which is ridiculous but I think it’s a start. I wear a red hoodie sometimes. A bit more velour. I’ve got those ripped jeans too. I don’t wear a huge amount of my stuff either. I don’t wear it because sometimes it’s out, or it needs to be in a shoot and I don’t want to get food all over it. I mean, literally, last night I ate dinner and within three minutes I had rice all down my front. In the studio, I’m covered in paint and markers. I wear Converse pretty much every single day as well. I can’t remember the last day I didn’t wear them.

SC: Where do you live in London and what drew you to the area?

RPM: East, but I’ve always lived here. I moved to student halls on Mare Street in 2008 and it was still a bit dodgy back then. A 14-year-old got stabbed outside my window, which didn’t have bars, and it was genuinely scary. I just never left the area.

SC: Favourite place to shop in London?

RPM: Oh my god, you know where my favourite place to shop is genuinely? Oxfam on Kingsland Road. Every time I go in there, I see something and I’m like I need to get this. Look at that leather jacket on the back of your chair. It was £8. Store wise, I like walking around Selfridges too.

SC: Favourite restaurant or bar in London?

RPM: I can’t remember the last time I ate food out. I guess my local is the Three Compasses in Dalston.

SC: Favourite place to relax in London?

RPM: I’d probably say the CSM library. I just sit in there even though it’s full of people, noisy, but I can always find something interesting in there. It’s a nice space.

SC: Favourite holiday destination or where would you live if not London?

RPM: Literally, somewhere really terrible. I want to find the worst, hot place in the world and move there. I want to buy a £15,000 house in a dump. You know At Home In The Sun? But yeah, somewhere in Spain. Freelancing here for two days, going back to Spain. That’s the dream.

Interview by Oliver Zarandi | Photography by Lillie Eiger