Interview: Tom Emerson & Stephanie Macdonald, 6a architects

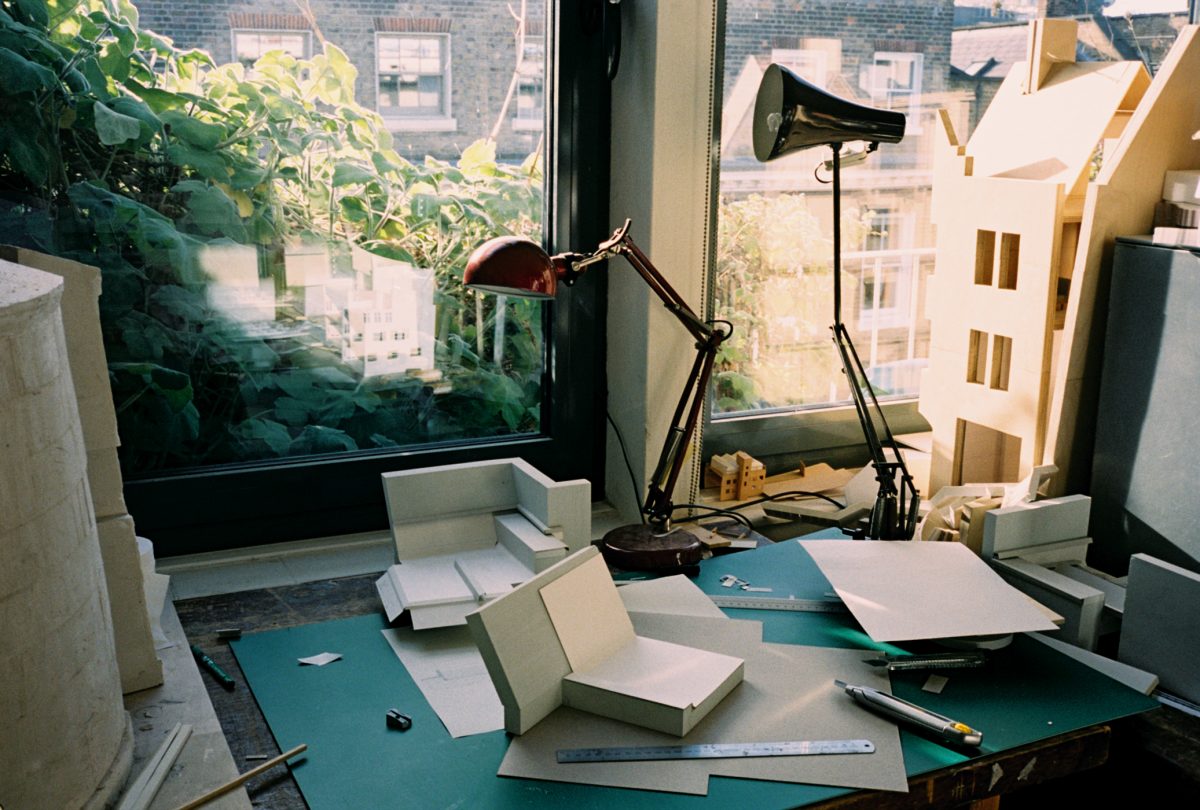

By Keshav AnandLondon-based architects Tom Emerson and Stephanie Macdonald’s practice, 6a architects, have garnered an impressive reputation for their sensitively built and engaging spaces, including contemporary art galleries, studios, educational buildings and residential projects. They have become the go-to for a number of the UK’s leading arts institutions, including Alex Sainsbury’s gallery, Raven Row, for which 6a won a RIBA Award in 2011 and were nominated for the Stirling Prize. Something Curated met with Macdonald and Emerson at their sun-filled office on Lamb’s Conduit Street to learn more about their journey into the field of architecture, working with Juergen Teller, and what 6a have planned next.

Something Curated: Can you tell us a bit about your backgrounds and how you got into this field?

Stephanie Macdonald: Kind of by accident I guess. I left school quite young, I worked for a short while in the City, and then went back to art college. I did a foundation in Croydon, followed by environmental art at Portsmouth Art College, which is where my interest in architecture started to grow. I wanted to stay with an art school, so I applied to Glasgow School of Art and went into the second year of architecture at the Mackintosh there. Tom and I then met at the Royal College of Art on the postgraduate architecture course. We moved from there to different diplomas at London Met and Cambridge and started the practice a year or so out of college. I guess it was a year or two out. It was when we had our son Laurie, which at first didn’t seem like the best time, but actually was a brilliant catalyst.

Tom Emerson: I grew up in France and Belgium, my parents were quite academic; they had a sabbatical to the States, and I did some babysitting for an architect, which I didn’t know at the time, but I thought his house and lifestyle were cool. When I found out what he did, I became interested in it, and it fit the fact that I liked making things, drawing, stuff like that. It somehow seemed to fit, but there are no architects in the family or anything. And then I came to college in the UK, I went to Bath and then worked and then met Steph at the RCA, and from there I went to Cambridge and I worked for Pierre d’Avoine for four years after college. In the life of an architect, that’s all pretty speedy stuff; architecture is a slow game.

SM: We might not look it but we’re extremely young architects. [Laughs]

TE: The studies take a long time. So it felt like it all happened quite quickly, from college and moving in together, to our son being born, to setting up the office. It all felt like one breath, even though it was quite a few years.

SC: Could you tell us a little bit about your practice, 6a, and the vision behind it? What were you hoping to achieve when you set it up?

SM: We wanted to make work that has a strong set of values behind it and has something to say. And that that something is useful to how the city’s constructed and, maybe, can move it on. We try to find a language that is engaged with what’s gone before and what we think may happen, or to reflect what is happening. We’ve always drawn influences quite naturally from all sorts of things. I guess at college we were looking very much at Georges Perec, a writer, the sculptor Richard Wentworth, and about ways of slowing down and looking at what you’ve actually got before you make an intervention. Whatever you do make takes part in the existing conversation. This is realised in the material you build with, a material essay, sometimes anecdotal, social or cultural, that becomes the core of the project. It is important to understand the language you are building in and what it is saying.

TE: When we were in college, the people whose work we were most influenced by, were very often not architects, they were artists, writers, or things like that. But if they were architects, they were architects who had found being in the visual arts as a certain alternative way to practice. There are ways of slightly subverting the professions and ways of making work, which is more abstract but also more connected to everyday life. Those were things we were interested in and tried to find our own way of responding to. In the early days, we were particularly looking at everyday life. The ordinary, which had been a subject in literature and in art for a long time. It’s sort of an interesting history, but not capital ‘H’ History. It’s the small histories that make up the world. And that’s really developed more and more, and it’s gone from the everyday life of the city to the now broader idea of nature. So, what we’re trying to do is make work that remains connected with the world that it sits in, but is also pointing towards new ways of living, new ways of being together, new ways of finding expression, the use of materials. What we do is not unique to us. There’s a group of people who are somehow all exploring similar issues.

SC: Could you speak about any projects that you’re currently working on?

TE: A lot of our work over the last few years has been in the arts: galleries, museums, studios. And the current one is the new contemporary art gallery in Milton Keynes, which is an enlargement of an existing small gallery. It’s a very big enlargement, so essentially it’s a new building, right on the edge of the city, between the city and the park. Milton Keynes, which in many walks of life gets quite bad press, is actually an extremely interesting city. A kind of post-war experiment which is really finding its feet now, as an environment, socially, and then hopefully the next step is culturally. The city is built around this axis, which ends abruptly into this huge park.

SM: It’s Campbell Park. It’s a funny intersection; the LA grid city meets solstice druid circles in the park. It’s at the edge of the city centre at the moment but if you think what Central Park was like right at the beginning – I think Campbell Park is a bit like that. It too will become surrounded by city buildings.

TE: So the city’s a grid, and the park is sort of mystical and orbital. Our building is essentially a grid, a big metal box, with a massive round window in it. It’s where the park smashes into the city in architectural form. It’s quite a simple, big project.

SM: It’s corrugated metal. It’s very reflective, and it’s very much got the language of the 60’s.

TE: We talked a lot about the history of the city, a really recent history. This is the history of the Modern, the post-war period. It’s a projection forward, which is very exciting. Construction is due to start in a month or two.

SC: What does London offer you as the location of your practice?

SM: It’s very metropolitan. Our practice has got 17 nationalities at the moment, and 19 languages between it. So we really love it for that.

TE: It’s got everything.

SM: It has everything really close. We can pop to a museum, a library, a show. It’s got every period of building; you look out of this window and you’ve got Georgian, 50’s, 90’s, you can look at every brick mark.

TE: Maybe to rephrase it: it’s not that it has everything, it’s that it is everything.

SM: It’s very tolerant as well.

TE: And I think it’s a city that will be what you want it to be on the day you want it to be that. It can have different moods; it can have different words. There’s no city that I know that somehow is everything and nothing at the same time.

SM: Also, it’s European. It’s international and European. London is European, apart from Westminster.

SC: Could you tell us a bit about your collaborative dynamic?

TE: It’s funny, that’s an extremely difficult thing to describe.

SM: We don’t know. We actually cannot describe it. We still can’t properly give ourselves separate roles.

TE: It’s one of those things that, because we met at college, and we did a few little projects together in college, and then we got together, we went on trips, we looked at stuff. It was a series of interconnected interests and that personal relationship, this weaves together, and by the time it’s professionalised, nobody’s entirely aware of what the constituent parts were.

SM: We consciously decided that we wanted to practice together, but we didn’t need to make rules about it. We just did it.

TE: But we ended up in it, doing it, probably without ever having really formalised why or how. We just did. Some of the stuff we do together, some of the stuff we do separately and then swap.

SM: And because you’re at home together, it’s not like anything doesn’t get discussed. Sometimes we can be really angry.

TE: Yeah, sometimes it’s very difficult and there’s a bit of stress.

SM: There isn’t a cut-off point where this is it. This is just what we do.

SC: How long has the practice been running for?

SM: 17 years, officially.

TE: Sometimes it’s convenient to say that the first project that we did that was visible, as opposed to a domestic project, which was oki-ni on Savile Row, is more or less the first moment that people became aware. But then there were a couple of projects that predate that.

SC: oki-ni, the fashion ecommerce site?

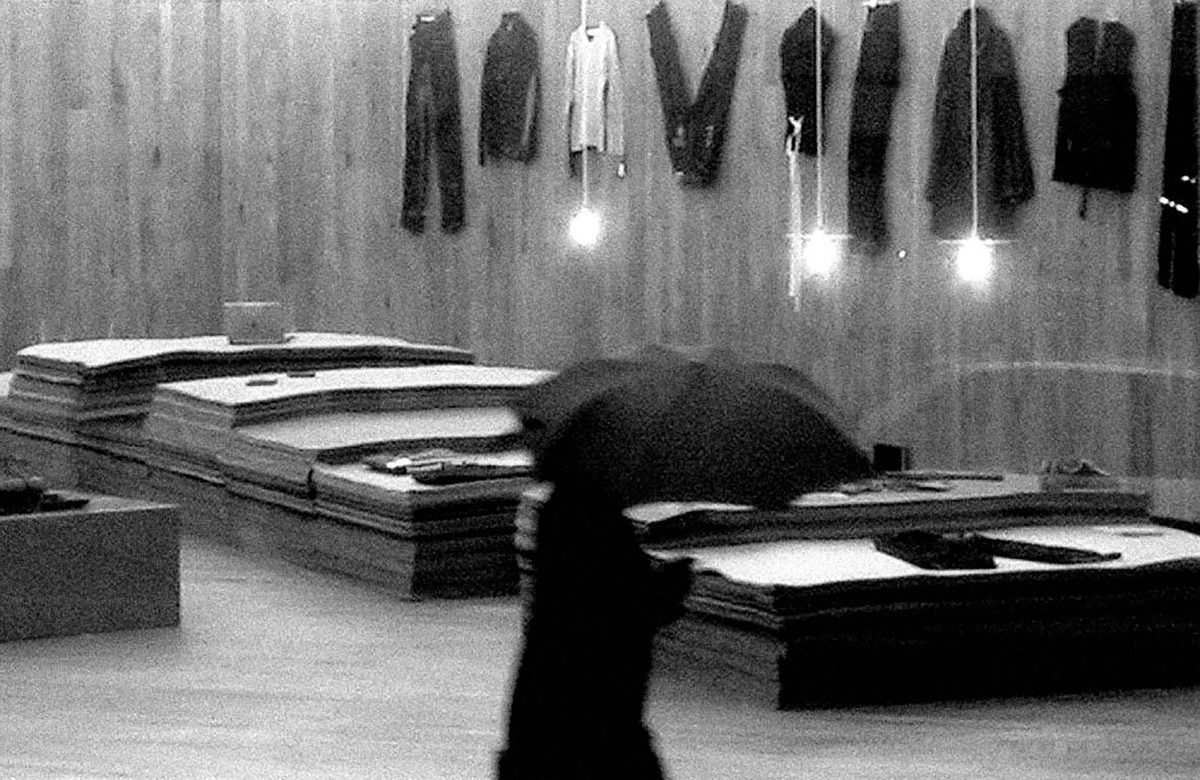

SM: Yes, we did their first store when they were launching the brand. So it was always with the intention that it would be an Internet retailer, but they wanted a physical space to grow a community around first. The idea of being able to go in, but not buy anything. You could order online in the store and it could be delivered to Tokyo the next day. In 2000, when we started the project, that was really massive.

TE: The thing that was amazing, I remember the guy who set it up was way ahead of his time. He was saying we could do it with some laptops that ran on Bluetooth, because Wi-Fi didn’t exist then. You could get things online on a laptop. And he said, “You know what? In a few years, people will be doing this on their phones.” And everyone replied, “Ha! On this? With this crap keyboard?”

SM: But he’d been living in Japan for 10 years, quite a nomadic lifestyle, between Europe and Tokyo within the fashion world.

TE: So yeah, to some extent, because origins and dates are always slightly difficult to find, that was, you could say, the first project.

SM: That was a pivotal first project that started to get published in the art press, and it really struck a chord. It went into Tate Magazine and Contemporary Magazine first rather than anything architectural, which is interesting.

SC: Where do you typically look for inspiration for a project? Is there any kind of system you’ve developed for approaching a new brief, or does it tend to be very organic?

SM: I think if there’s a methodology, it’s about looking at what you’ve got, and then beginning to draw connections. A survey of sorts but quite lateral. There’s quite a bit of research that goes in. It might be archives, but we’re not historical architects. It’s not about being purists.

TE: I suppose you develop a more critical way of teasing out the knowledge that will generate ideas from those things. Could be context, could be anything. It may be the client and their temperament and their practice, or it may be the institution and what it represents. You become quite tuned to where you think the richest material scene will be. And usually it’s more than one, and the interaction between more than one, that reveals something. You could say there are two parts to it. There’s one which is research-based, whether it be archival or natural or surveys. And the other one has to do with experiments that we make with processes, materials and forms. It’s when you have the experiment on one side that really connects with something you discovered in the research, that things seem to find their own life.

SC: What do you think are the issues that architecture needs to try and solve in London at present?

TE: We talked about London earlier on, I said it’s sort of everything, so it’s problems are very multiple. I would say that there is something which I don’t know if architecture can solve, but could certainly do a lot of damage: the unregulated expansion of the city, particularly eastwards and along the river, which is something that is incredibly difficult to fix but very quick to damage. If you look from The City eastwards, on both sides of the Thames, the huge expansion of housing, essentially speculator-led housing, towers along the river, is in a generation going to seem absurd.

SM: It’s not just to do with The City, it’s more to do with developer-led housing, with housing being commodified, really. It’s the biggest issue. It feels like nobody’s got a social vision about what the city is, it’s just, “I own this plot.” London has always had an aspect of that. The Georgians were the biggest developers really, and that was private in a way. But there does seem to be a real lack of vision about how housing is kept in the city.

TE: I guess we’re quite hopeful that Sadiq Khan – it’s the early days of his period in office – but he seems much more switched on than, let’s say, Boris Johnson was about what needs to be put in place to slightly check the rampant capitalism that has run through the city.

SC: What was the narrative behind the South London Gallery garden?

SM: Our first work with SLG, completed in 2010, expanded it from essentially one big gallery room to using the whole site, absorbing a derelict terrace house and garden and creating a series of differently scaled indoor and outdoor rooms in which they show art. The largest outdoor courtyard at the rear was empty and we had begun to re-orientate the gallery towards it, opening up the building to it. It is the way the kids come in from the neighbouring Sceaux estate, which the gallery has worked with for years and they wanted to turn the back gate into a new main entrance. Margot Heller, the director, had always wanted Gabriel Orozco to design a garden for this space. He said yes and we worked with Gabriel to help realise it.

During the project, it went from him designing a garden to the garden being the artwork. Gabriel works with both found situations and his own interventions of geometry. His recognition of what is there already is sympathetic to the architectural approach of the building. The unruliness of south London derelict sites and backs and the history of the site as an old bombsite led him to reimagine it as a kind of overgrown ruin. A series of rooms was created by the planting. We worked with horticulturalists from Kew Gardens; Gabriel visited Kew and chose plants for their sculptural shape, rather than strictly geographically, so things from the Mediterranean sit next to something from New Zealand.

The south London landscape of brick buildings and York stone paving was abstracted and York stone, cut to brick dimensions, and was laid in a topographic textile across the site. Its geometry was set out on the radius of the oversize door swing of the education studio opening onto the courtyard. It’s all sand bedded so that the planting will come through and ultimately the geometry of the stone that you see now will be delineated in the green of moss and plants.

SC: Presumably your schedules are massively varied but would there be a vague day-to-day routine that you could describe?

SM: There are a few things that are routine, but it can also be really varied as well. I mean, we come into the studio, but site visits, client meetings and research can take us all over.

TE: The day, you could say, starts not outrageously early but earlyish. It’s the drift into the evening and the weekend, which is quite variable, which might be on one level, graft with deadlines pressing, stuff like that. On the other side, is when the work sort of drifts into the social and other fields.

SM: There’s also a really nice side, which is every project has a specific materiality to it. We’ll often be at things like a reclaimed timber yard picking out a floor, for example, for Churchill College. Cecile, our project architect for it, was in France, in a chateau being taken around to see all the timber, and there was only one place that we could find as much timber as we needed, and the client had to get it straight away. And last week, I went to Harwells, an amazing slipcast terracotta factory up in Blackburn. So you get to learn loads. And we went down to a foundry with Paul Smith when we were casting the Albemarle Street façade. You do find yourself in lots of odd places, but you’re as likely to be crawling around the top of the V&A Museum dome or underneath somebody else’s basement looking for services. It could just be anything.

SC: In your opinion, what is one of the best completed architectural projects of the last decade and why?

TE: I’m trying to think of what I’ve seen recently. Just because it relates to a couple of questions about London throughout this conversation: Tate Modern has been amazing, at a much bigger level than architecture. Architecture is fundamental to it, but then what it’s done for culture, what it’s done for the city. And not without its tricky parts, politically and stuff like that. But it’s amazing how far it’s gone beyond just making a new museum. It’s incredibly bold to take on an old power station.

SM: This is London’s biggest public space and anyone can go there. And they’ve just done it again with the new Switch House tower; it is the funniest thing being on the top deck and looking into those really big huge flats, but that’s one of the most social buildings actually. I’d say that’s one of the most exciting I’ve been in. I would’ve gone further back and said Bo Bardi, but I think for some of the same reasons; it has a lot of the same qualities of that actually. Bo Bardi’s SESC Pompéia in São Paulo is really a beautiful use of an old factory. Also, at a very different scale, Brick House by Caruso St. John, that Rod Hayes worked on in their studio. It’s elbowed in between a back site in London over in Westbourne Grove. It’s really beautiful.

SC: Could you talk to us about your experience working on Juergen Teller’s studio?

TE: He was a wonderful and inspiring guy to work with. One of the things that was nice was that there’s a kind of directness, which is in his work actually. Very open. It wasn’t a process that was full of complexity, which sometimes projects can have, where you have to do option after option in order for a client to make sure that they feel like they have exercised all their choices at every stage. But with Juergen, he made very specific requests at the beginning, which we discussed in the early stages. Once he felt that the project had got its identity and its character, then he was very happy to let us get on with the work. He didn’t art direct it from behind. He was fascinated, but he was very open, and he was interested in what we thought was worth pursuing and developing.

SM: He’s incredibly visual with everything, obviously. He would look at stuff, see visuals get very attached to certain aspects. Then if it had to change, that would be terrible for a bit, but then he’d come around to it. His reactions felt very extreme – extreme attachment, but he would reflect and then be totally open and curious about another way of doing something. He has a disarming candour.

TE: He was fantastic in that he was brilliantly uncompromising. Once he was committed to a way of doing something, he would never steer away from it. He had an incredible resolve.

SM: And with planning and things, various issues, he didn’t lose confidence.

SC: Is it designed as a live-work space or just a studio?

SM: Just a studio. But the way that he works is very much with a small gang who do stuff with him – they are based more in the first building – and then he works very specifically with an assistant, and that’s in the big studio in the middle. The building at the end is more kitchen, library, and sauna. It is a more reflective space, one where he can go with one client and talk with them; there’s a way of being quite domestic and relaxing beforehand. When there’s a large shoot the whole complex might be used and the entire wardrobe goes in there and everything else.

TE: Essentially, the entire building, or all three buildings, are all places to take photographs, places to make work. The water butt is not part of the studio, per se, in the brief. But it is a place to take a photograph.

SM: The gardens have been used as a studio, with plenty of stuff coming out of there. Charlotte Rampling drinking milk with a fox as well as Juergen in the water butt.

SC: Are there any particular materials or types of spaces that you currently really enjoy working with?

SM: It’s quite case specific. We really enjoy working with different things. We like concrete and block work. Timber we’ve used quite a lot. Just getting into the slipcast terracotta.

TE: We tend to have quite a focus on certain materials. But I would say, if anything, you’re going to find themes. I’m not sure if they’re preferences or themes in 2010, not by our own doing, but somehow history was in the air in a very direct way, and then in the last few years we’ve been more directed toward gardens and the relationship between architecture space and nature. Partly because it’s a theme that we’re interested in, partly because the projects have sort of taken us there.

SM: Yeah, I don’t know which one’s leading which.

TE: I think if you’re smart, you develop an interest in the things that are in front of you.

SC: Could you tell us about your influences when selecting charcoal to work with for Raven Row?

SM: That came out of a photograph found at the London Metropolitan Archive that showed a terrible fire that had happened in the 1970’s. All the architectural mouldings of the rooms that were on the first floor facing the back roof courtyard had remained completely intact, but surviving only as totally solid charcoal. So that became the generator for charcoal cladding and cast iron against charcoal. We were experimenting with blowtorches; Takeshi, our project architect, was only getting really weedy bits of charcoal, and then he went home to Japan, and actually very close to his village, they use charcoal as the cladding for homes. It’s weatherproof, insect-proof, fireproof. And it’s really thick. So he found out how they did it, and then he came back with this Japanese method and the contractor went into this with his Serbian workforce on his farm in Hertfordshire. It’s a funny cultural mash-up.

SC: Is there a project that you feel is your proudest achievement?

TE: I think it’s like asking which of your children do you prefer. In a sense, you love them all, even the ones that are troubled. It’s not that the projects aren’t without regret. In some respects, I think your favourite project is the one you’re doing now. That’s the one where you feel like you invested yourself in it. But then, it’s also nice to go back and see projects. Sometimes you feel a bit uncomfortable about them, maybe recently. And then once they get a little bit older …

SM: You definitely see all the flaws right at the end. It takes a bit of a while to forget. I think we’re really proud of all the projects we’ve done.

SC: Why do you think a number of prominent art institutions have been drawn to working with your practice?

SM: Having been through art school first, a lot of our friends were artists, and I think there’s a very natural conversation about how art is shown. And making an authentic art space, one that’s aware of what it’s building in, because artists are so sensitive to that: how their painting is situated, or their sculpture, or what their floor is. Everything’s talking. All of that stuff is magnified in an art gallery, and I think it might be our awareness of that, if that is what we’re working with, that is perhaps one of the reasons. And maybe our architecture is a little more reticent. Generally, we’re interested in making something very beautiful and material and flexible. Flexible is a difficult word, but something that can be used in lots of different ways.

TE: There are probably lots of reasons, some of which we don’t know. I would say, in some ways we manage to make architecture that is quite restrained, really visually restrained, which suits the art world in terms of existence I think, without losing presence or character. And I think that that’s something, which, as Steph just said, is quite a fine line between disappearing and being completely banal and bland.

SM: A very fine line between disappearing and still being something of real character and place-making.

SC: What piece of advice would you offer to an aspiring architect?

SM: It’s an amazing subject. Go for it. Also, I would say, lots of people when they’re younger come to us and say, “I’m not really good at maths,” or “I don’t do art.” I would just say the subject is so broad, there are so many different skillsets that it absorbs, that if you like it and you want to do it, there’s a way of being able to do that.

SC: What drew you to this area of London?

TE: Opportunity. We found a space here soon after college, and it was beautiful and decrepit and cheap and exciting, and we moved in and fell in love with the area.

SM: As we said, we set up the practice when we had our son, and it has Coram’s Fields at the end, which is one of the only children’s parks; you’re not allowed in unless you’re accompanied by a child. And then the area is amazing here, because it’s quite a hidden kind of residential community, but there’s all the business as well. Lamb’s Conduit Street has really changed in character. It’s got fantastic, very independent people: Oliver Spencer, Folk, all lovely people. We’ve known them now for 20 years.

SC: Where are your favourite places to eat in London?

SM: Great Queen Street and Ciao Bella.

TE: I like Cigala at the end of the road.

SC: Favourite place to shop?

SM: Folk. I’m very bad. My walk to work is that way, and next thing I know I’m in there. They are lovely – I like that they curate a great set of designers as well as their own clothes.

TE: I really like going on a cycle ride on Saturday morning around Mayfair and St. James’s. On Sackville Street, I think, there’s a fantastic antiquarian bookshop. Not so much shopping, more for kind of browsing and watching the world.

SC: Favourite travel destination or where would you live if not London?

SM: Sicily. We’ve been going there for the last few years.

TE: Same answer.

Interview by Keshav Anand | Photography by Lillie Eiger