Interview: Designer Ben Kelly On His Versatile Practice & Collaborating With Virgil Abloh

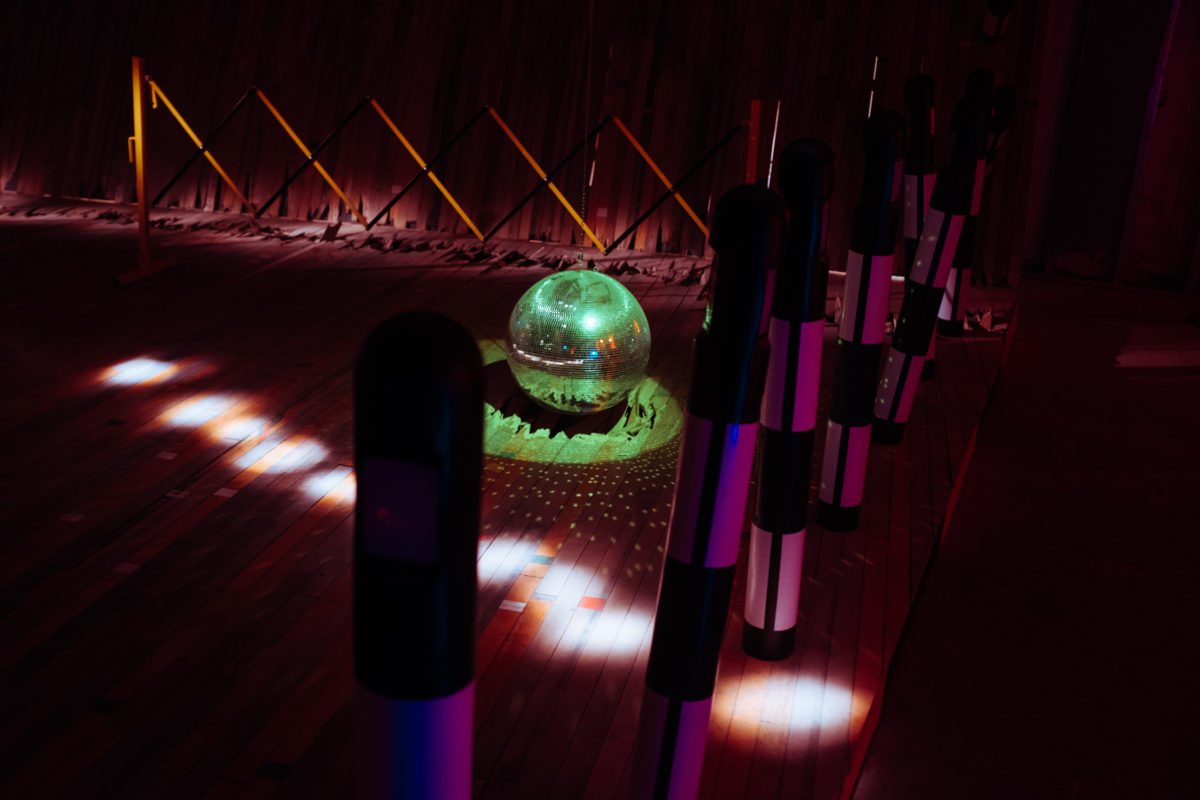

By Something CuratedBen Kelly is recognised as a pioneer in the practice of interior design, continuing to inspire the work of his contemporaries. Recently appointed as Professor of Interior Design at Kingston University, Kelly currently has work on show at Somerset House and 180 The Strand, where he has collaborated with Off-White’s Virgil Abloh on an immersive artwork, entitled RUIN, piecing together fragments of abandoned nightclubs, iconic discos and cut-ups of dance music history. Something Curated met with Kelly in the run up to RUIN’s opening to learn more.

Something Curated: Can you give us some insight into your background; how did you enter the field of interior design?

Ben Kelly: After completing a foundation course and a bachelors, I went to the Royal College of Art to do a masters in Interior Design, and I’ve been working for myself ever since. I wanted to be an artist but for some reason I got really interested in interior design – it might have been partly to do with that time in the 60s, when there was a lot of interesting stuff going on, particularly from the Italians. There was some quite avant-garde design and that’s what got me interested I think, but I’ve always tried to somehow straddle the line between art and design. I’ve run a commercial practice, an interior design practice, from 1976 with kind of one foot in the art world in some way or another, which has been great.

SC: Do you have certain principles that guide your work?

BK: You would certainly recognise any of our projects I would like to think. I’ve always been drawn to real materials. I’m seriously interested in work by Marcel Duchamp, almost to a point of obsession – you somehow take something out of context and you put it next to other things and something else happens, so that’s always there in the work. Another thing, I’ve always been interested in colour and never been afraid to use it.

SC: Your work often includes industrial elements with bold colour – is that fair to say and why is that a recurring theme?

BK: Industrial materials are something that I’ve always been interested in because of their robustness and longevity. When you take those industrial materials out of context from what they were originally made for and put them in a different environment with natural materials like timber, something else happens. I’ve talked about the language of materials in the past and its trying to put together something that sings, it’s like music, like a painting, like wanting it to be lyrical and have a life – but the projects are commercial and clients have a budget and it all has to be honed down to do its job.

I did a job a long time ago; it was a hair salon called Smile on the King’s Road, almost next-door to the Vivienne Westwood shop. I had used the colour orange for that interior, and a magazine did a big piece on it. I think it was The World of Interiors, which is usually expensive, domestic interiors but they did Smile; anyway, the journalist wrote in that piece, “Ben Kelly rescues the colour orange from the scrapheap of style.” What more can I ask for? That is going on my tombstone. Colours can go in and out of fashion, there are taboo colours, certain colours you are not supposed to put together, there is a whole rulebook about how you should or shouldn’t use colour and they are there to be challenged and broken.

SC: How would you say your practice has evolved over time?

BK: In the beginning, the projects that I was getting were from friends or likeminded clients, people around my age who were starting to open shops. Then I got involved with Factory Records in Manchester, who were fairly anarchic and chaotic but I got a very big piece of work there, which was The Haçienda nightclub in Manchester, and that became a stepping stone, a platform for me that led on to other projects. As a result of The Haçienda I was invited to pitch for a job at the Science Museum, for the basement. My ambition was to be in the public sector, so that my work affected everybody and not just young kids or likeminded people.

When I was pitching for that job against lots of big architectural practices, we got onto a long-list and then to a shortlist and then, after the presentation, the Design Director of the museum whispered in my ear, “Wouldn’t it be great Ben if you got this job? You could do a Haçienda for kids!” That’s genius, I thought. After that I was so determined to win that job. We won it, and I painted stripes on a column in the Science Museum referencing the nightclub. I saw that Virgil Abloh was making stripes on garments and now we’ve collaborated in 180 the Strand – it feels like it’s gone full circle. The Haçienda never dies; it goes on forever.

SC: Can you talk to us about RUIN; what is the project about?

BK: I had designed a tour set for Virgil and then did some merchandise. I introduced Virgil to the owner of this building, who puts on all these art shows, and he was very keen on doing a collaborative piece. We were offered the most fantastic space to do something, and I came up with the idea of a ruined nightclub. It seemed to kind of sum up were things are at the moment – I wanted to make a statement about nightclubs closing; entry into places is so expensive that young people can’t afford to go into them and it seemed like a death. I wanted a space where there could be DJ nights happening, there could be dance, performances, private parties, whatever.

SC: What was the process like collaborating with Virgil Abloh?

BK: Collaborating with Virgil is like collaborating with an aeroplane; he lives in Chicago, his PA is in New York, Off-White is in Milan, he is constantly going around the world doing so many things so we communicated by text mostly, occasionally email, and very occasionally we’d meet up. But he’s amazing – he can sew the seed of an idea or you can put an idea forward and from that he will promote and support it.

Really, the collaboration is about the common understanding that we have about the way certain things work and how certain things have happened. It’s also about showing young people where things came from and the kind of journey, the progress of how something became another. For me, being a bit angry in the first instance when I saw Virgil’s Off-White things before I knew anything about Off-White or Virgil, to understanding the word skimming, as Virgil said that’s what it is – it’s like with music when they sample, skimming is the same as sampling. Its making references to things, taking a bit of this, a bit of that, and carefully putting them together to create a new recipe.

SC: Can you tell us about the work you are currently presenting at the NORTH: Fashioning Identity exhibition at Somerset House?

BK: The work at the exhibition North is from the touring set that I designed for Virgil, conceived as a set that can be used when he does DJ spots anywhere in the world, or if he does a fashion show or any event it’s a kit that packs down into fly cases. I call it Off-Set for Off-White.

SC: Are there any particular materials or types of spaces that you enjoy working with?

BK: Making RUIN was a very weird process because I had to design it but then I had to kind of make it ruined. Usually you build something and make it last and over time it will possibly disintegrate. I had to carefully disintegrate something, which is an alien process but it’s been incredibly informative and it’s kind of changing the way I’m thinking about what the next project is going to be. I’m interested in a thing called Palimpsest, which is about layering an early form of writing.

SC: How has design changed as a discipline over the last few years?

BK: It has just become unbelievably commercial and it’s become much harder, but has much less, it’s more competitive, everything is branded, things don’t last very long, everything is very thin and I’m not very happy with it. The high-street has died a death and to me, really it’s up to the young people to start doing something for themselves. It’s really difficult – there is good work being done but it’s pretty hard to find.

SC: You have worked on a vast range of interiors from museums to gyms – do you have a favourite or particularly formative project?

BK: With my practice I’ve always tried to keep it as open and broad as possible and not focus on one area of the market. I think we ended up reinventing health clubs with the Gymbox project – they are kind of like nightclubs but they are gyms, every one has a boxing ring in it, they sometimes have live music or DJs, and it’s a new fresh way of thinking about how you might keep fit. A favourite project we did was a little bar in Glasgow called Bar 10; sadly it isn’t there anymore but that was a real crafted piece of work and the design and architecture community in Scotland loved that piece, and they tried to get it listed, which was a massive compliment. But above all, The Haçienda has been the most important because of what it became.

SC: Are there any upcoming projects that you can talk about?

BK: I closed my office about a year and a half ago and I now work independently, but I have a long-standing relationship with another design company called Brinkworth. So if I get a good project that I can’t do on my own I take it to them and we do a collaboration on that – they have the resources in their office to do big drawing packages. We’ve just done a nightclub in Los Angeles, which hopefully will open spring next year.

SC: What are you currently reading?

BK: I’m reading an interview with Marcel Duchamp.

SC: Favourite recent exhibition in London?

BK: There is a good one called RUIN.

SC: Favourite restaurant in London?

BK: St. John.

SC: Favourite travel destination or where would you live if not London?

BK: Cap D’Antibes – there is such an old fashioned luxury there, the sea is great, food is great, it’s ridiculously expensive so that won’t happen but I’m spending Christmas and New Years in New York. One of my favourite places to go to is a village in North Yorkshire called Appletreewick.