Interview: Artist Robert Montgomery On ‘Parasolstice – Winter Light’ & More

By Something CuratedKnown for being able to transform chaotic streets into reflective spaces, Robert Montgomery’s text art brings out the thoughts of the city’s collective unconscious through his billboard poems, dramatic light pieces or ephemeral fire hoardings. Responding to the psychogeography of Old Street, where elements such as William Blake’s grave coexist with a neo-liberalist architecture that embodies the city’s financial system, Montgomery’s site-specific work on the terrace at Parasol unit rethinks East London’s urbanisation. Something Curated met with the artist at the gallery to learn more about his career and the making of this show.

Something Curated: Could you tell us a little about your journey into this field?

Robert Montgomery: As a young artist I loved the work of Jenny Holzer and the way she would bring these vivid anonymous statements into the city. Among other text artists like Lawrence Weiner and Ian Hamilton Finlay, Jenny Holzer was my biggest inspiration.

SC: Did these references influence you to choose your medium, using text over billboards?

RM: I decided to work over billboards to sort of merge what artists like Holzer were doing with what I saw activists like AdBusters doing. My idea was to “turn off” the language of the advertising and to bring in other kinds of language; I wanted my language to sometimes seem like the collective unconscious of the city speaking, and sometimes the rantings of a mad man, sometimes the voice of a broken-hearted lover. People sometimes don’t understand that the voices in my work aren’t me speaking necessarily- they are a collage.

SC: What is the assemblage of this collage like and how do you build up this dialogue between your work and a public surrounding?

RM: I think it’s due to having that collage of voices and the text echoing something that’s in the air. The best way I can describe it is to pull things from the collective unconscious.

SC: It could be said that aspects of your work are similar to that of a street artist, as your billboards are often made site specifically in public spaces. How do you relate to the psychogeography of each area?

RM: My billboards aren’t particularly made site-specific except that a billboard is the “ground” or the canvas and the text for me is like the “painting”- the billboard works are made for billboards in cities in general mostly. But my light works are more often site-specific.

SC: Could you expand on Parasolstice – Winter Light and how it is related to this area of London?

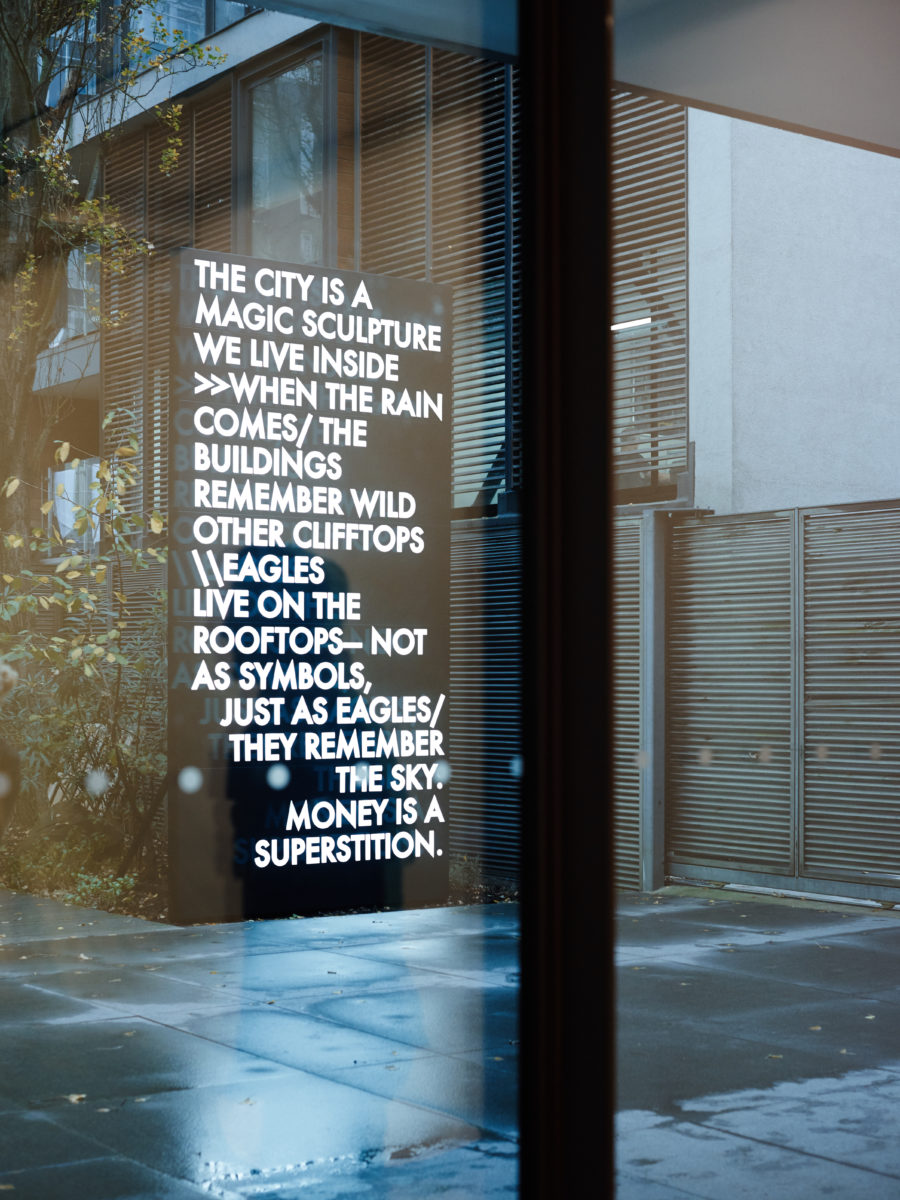

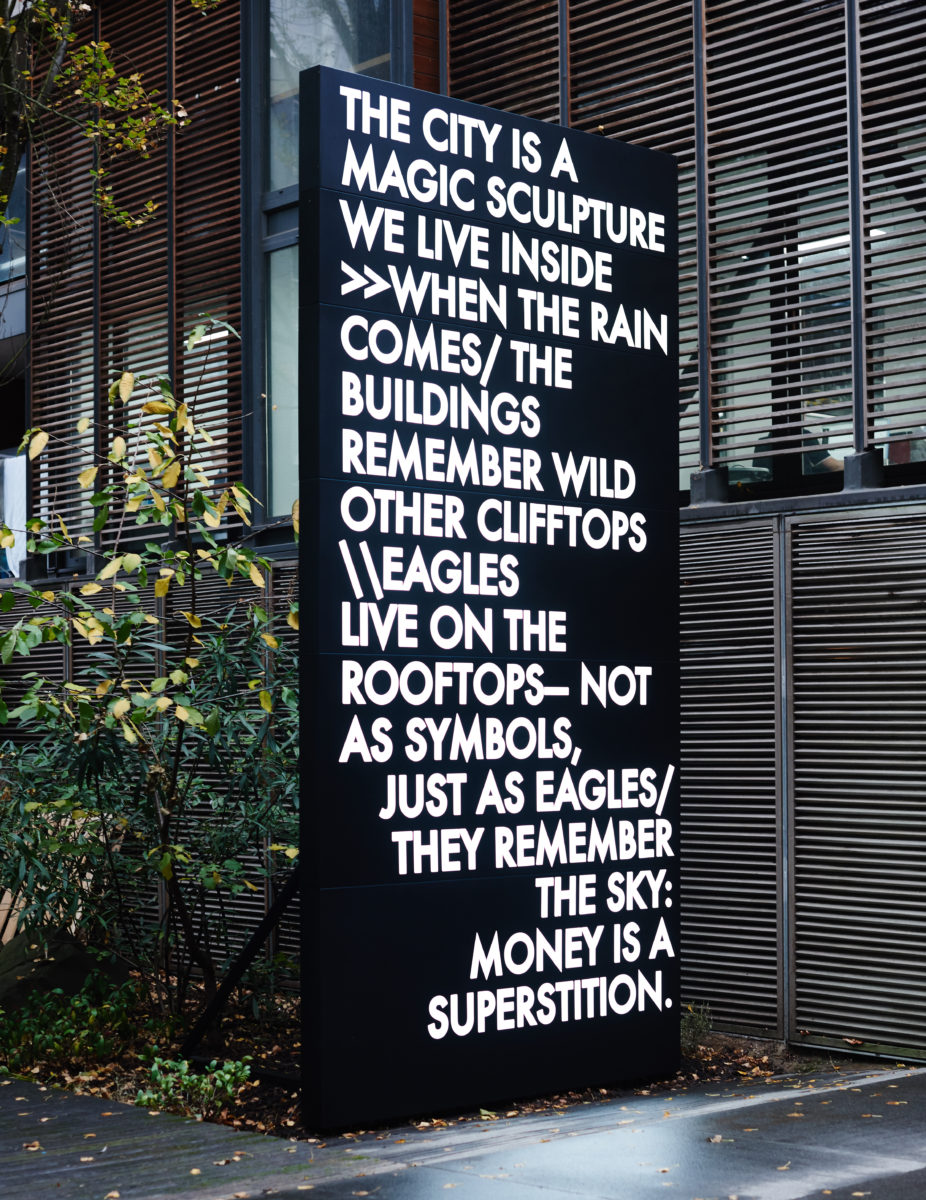

RM: The text for my Parasol unit commission came from a longer text I was writing in my notebooks with the same title as the final piece, “Poem in Lights to be scattered in the Square Mile.” In 2015 I was living in my old studio on Commercial Street and my view was across Spitalfields Market to the Gherkin and the RBS headquarters. So it’s a response to this particular area of London very close to Parasol unit where you have historically important places like Spitalfields and William Blake’s grave at Bunhill Fields side by side with these modern glass towers that are monuments to capitalism and money. Some days the high-rise buildings in the Square Mile seemed like wild vertical cliffs to me, and I always feel like buildings become landscape when you really tune in to them. So the text is like a landscape painting of the area really and an attempt to reclaim it as “nature” in my own head which you can see in the lines, “EAGLES LIVE ON THE ROOFTOPS NOT AS SYMBOLS JUST AS EAGLES, THEY REMEMBER THE SKY, MONEY IS A SUPERSTITION.”

SC: How was the process when selecting the text to include in this exhibition?

RM: It was easy. As soon as I saw the bird statue on the roof of The Eagle pub very close the gallery I knew I wanted to adapt the text I was working on about the landscape of the Square Mile and make it into something vertical and metal – a monolith shape that would echo the high-rise buildings. This part of London is going through a kind of “Manhattanisation” with high-rises going up everywhere.

SC: What are your expectations or hopes of the London public’s reaction to this project?

RM: I just want the piece to encourage a more vivid experience of the place, this unique city landscape where you have the spiritualism of William Blake and John Bunyan who are both buried closeby vying for psychological space with the architecture of neo-liberalism and Europe’s financial and banking centre, I love that tension.

SC: I’ve read you are an acolyte of the situationist movement. Can you expand a bit on how you relate your practice to it?

RM: I really liked Guy Debord as a writer, I liked the broken-heartedness of it. Unlike other post-Marxists he wasn’t really looking at the material world, he was looking at what an extreme version of capitalism would do to the inside of us, how it might break our hearts. Also Debord could see the future he could see how the popular media would swamp our consciousness, take over our consciousness and attempt to replace the real world. When you re-read “Society of The Spectacle” now in the age of smartphones you realise we all carry the spectacle in our pockets, we live intimately with the spectacle, the spectacle is on us now and in us now, what Debord feared came true.

SC: What comes first, the space or the text? And how do you allocate each text to different spaces?

RM: That’s a chaotic system. I keep notes with texts and when I have a space to work in I go back through them and try to find things I can condense down short enough to become an art piece.

SC: As a politically engaged artist, what is your token on art and politics? Is there much art can do in today’s often-called distracted society?

RM: I think you can bring up subjects for debate in your work and then you can also help for real. I talk about political issues in my work and I try to help charities and causes when I can. I gave 10% of the sales from my last show at Cob Gallery to the Help Refugees charity who I think are doing amazing work, and that’s a way to help for real. It can be a bit of a minefield when artists get involved in politics and people can like to criticise you for it, but I think artists should be brave and try to do what we can.

SC: You were born and raised in Scotland. What made you move to London? And how has your artistic career been influenced by the city’s creative scene?

RM: I moved to London for the excitement and multi-culturalism of London and I stayed because that excitement and multi-culturalism now feels like home. I’m not sure how it’s influenced my work but it must have. I tend to go into London’s artistic history for inspiration, for example I’m making a work for the gallery at Canary Wharf that opens this month that’s dedicated to Wyndham Lewis, I think his graphic magazine BLAST which he published in 1915 is a great early work of concrete poetry, so at the moment I’m fascinated by early 20th century London modernism.

SC: What are your favourite cultural venues in London?

RM: I like the Hayward Gallery a lot. I’ve really missed it while it’s been closed for refurbishment and I’m looking forward to it re-opening early this year. I love National Theatre too and that whole Southbank cultural quarter very much. I love the Curzon Cinema in Soho, I hope someone manages to save it.

SC: What are you currently reading?

RM: I’m reading “Year of the Propaganda Corrupted Plebiscites: The New River Press Yearbook 2017” it’s a collection of new poetry by around 100 contemporary poets published by New River Press, the poetry press me and my wife the poet Greta Bellamacina helped to found, Greta’s new book of selected poems which has just been published and I think is profoundly good, and “Widow Basquiat” by Jennifer Clement which Greta bought me the other day to cheer me up when I was sad.

Interview by Marta Faria | Photography by Richard Kovacs