What Is Ikebana?

By Something CuratedThe Japanese art of Ikebana dates back to the 7th century when floral offerings were made at temple altars. These flower arrangements were later brought into domestic spaces, placed within specifically designed alcoves in the home. The pastime of viewing plants and appreciating flowers throughout the seasons was established in Japan early on through the aristocracy. Ikebana reached its first zenith under the influence of Buddhism and has grown over the centuries, with over 1000 different schools in Japan and abroad at present.

Though plants play an important role in the native Shinto religion, Buddhism, introduced to Japan in the 6th century through China and Korea, made flower offerings commonplace. The first systemised flower arrangements were known as shin-no-hana, simply meaning “central flower arrangement”. A huge branch of pine or cryptomeria stood in the middle, and around the tree were placed three or five seasonable flowers. These branches and stems were put in vases in upright positions without attempt at artificial curves. It was perhaps the first documented attempt to represent natural scenery.

In the 15th century, the celebrated Japanese painter Sōami conceived the idea of representing the three elements, heaven, human, and earth, from which grew the principles of the art form, still used today. Ikebana has always been considered a dignified accomplishment, and Japan’s most celebrated generals have been masters of this art, finding that it calmed their minds and made clear their decisions for the field of combat.

A principal authority in the field, author and professor Shōzō Satō has penned numerous books on the subject, and was awarded the Order of Sacred Treasure from the Emperor of Japan for his contributions in teaching the country’s traditions. Satō explains: “To the great majority of Japanese, each flower evokes a particular month of the year and the feelings and memories appropriate to that month. Ikebana arrangements, accordingly, are expected not only to establish a link between man and nature but also create a mood or atmosphere appropriate to the season, and even to the occasion – a tradition in keeping with the Japanese focus on the ephemeral nature of life, as well.”

Broadly speaking, the three pervading categories of the art form are Rikka, Shoka and Freestyle. Rikka was developed in the 16th century, and is perhaps the most traditional, while Shoka‘s origins are in the simpler Ikebana of the 18th century. Freestyle can be arranged as an abstract or naturalistic composition and is well suited to contemporary environments and tastes. The emphasis with this style is self-expression using, if required, man-made materials in addition to plants to create a desired aesthetic.

Ikebana continues to provide inspiration for a multitude of contemporary artists, stylists and designers, many of whom are combining the art form with other fields, subverting and reimagining the longstanding system. The Ichiyo School of Ikebana, founded in 1937 in Japan, uses a simplified and methodical way of teaching, encouraging personal interpretation, with classes for any level now bookable in London through Daiwa Foundation Japan House.

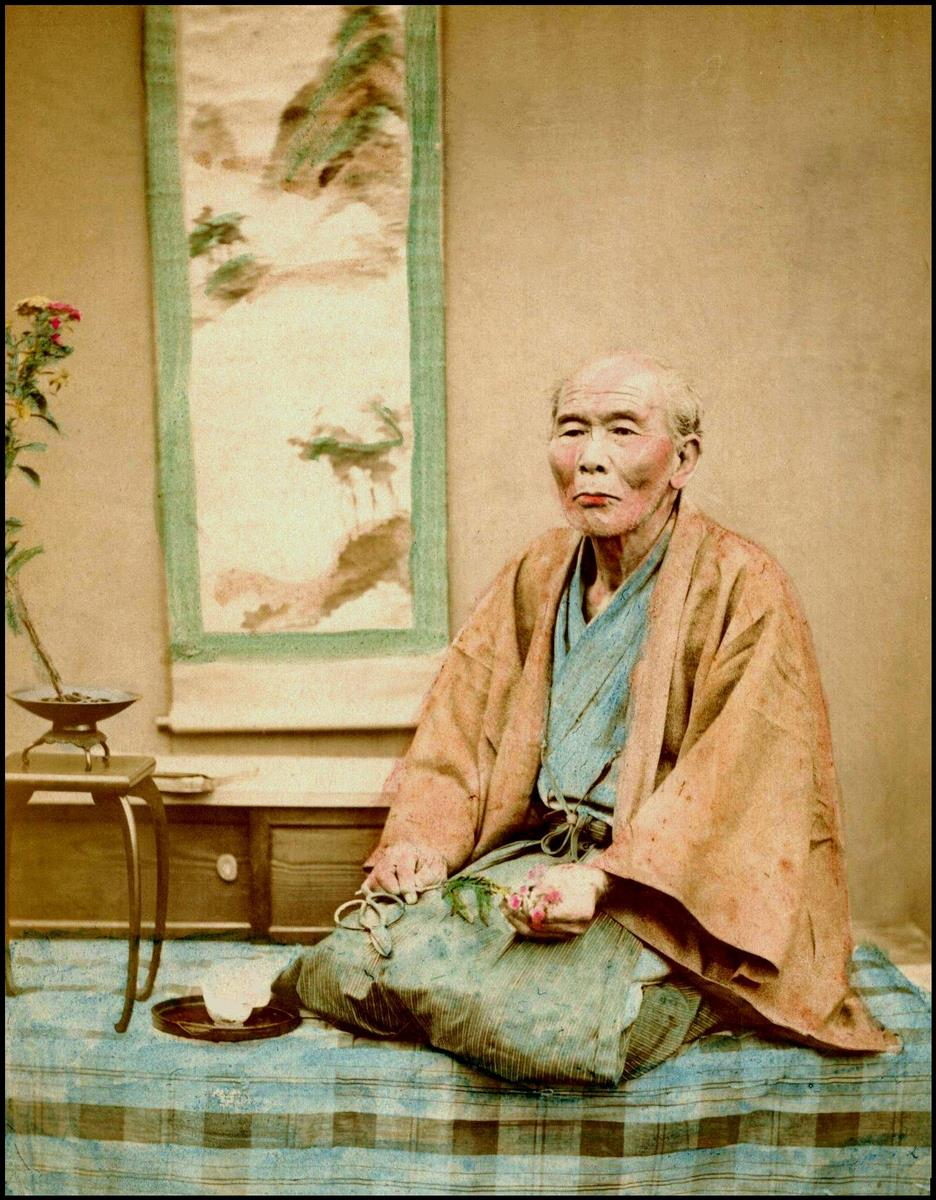

Feature image via Jeffrey Friedl