Interview: Catherine Wood, Senior Curator, International Art (Performance) At Tate Modern

By Something CuratedCatherine Wood was instrumental in founding the performance programme at Tate in 2003 and has since curated more than two hundred live works, both at the museum and within the online space Performance Room which she initiated in 2011. As Senior Curator, International Art (Performance), Wood works on performance projects, exhibitions, collections, having been critical in the acquisition of works by Joan Jonas, Tino Sehgal and Suzanne Lacy among many others, and displays at Tate Modern, as well as being actively engaged in research. We met with Wood to learn more about working in The Tanks, the BMW Tate Live Exhibition 2018, Tania Bruguera’s new commission, and more.

Something Curated: Can you talk to us about your journey into the art world? Was curation something you’d always had an interest in pursuing?

Catherine Wood: I didn’t know what a curator was until I landed a job in the publishing department of the British Museum, and a temporary job as a ‘curatorial assistant’ came up in the Department of Medieval and Later Antiquities. I had studied art history at Cambridge, after doing an Art Foundation in Hastings, and I loved what I saw of being a curator at the BM because of the combination of practical work (handling objects, organising displays) balanced with deep research. Our director at Tate Modern, Frances Morris, said a museum is “a university with a playground attached”, and this sums up what I love about my job: I am passionate about research and ideas, but never wanted to be a pure academic.

I’m interested in the encounter with art, and with learning from artists. The connecting link to the contemporary art world for me was a part-time job I was lucky to get with Maureen Paley in her gallery Interim Art in the East End, whilst I was studying part-time for my MA in Modernism at UCL. My job was mostly just minding the gallery at weekends and helping at private views, but entering Maureen’s world was an incredible education: she had amazing books! But also about the important role played by the commercial side of the art world, an opportunity to go to Basel and Berlin art fairs, as well as an introduction to some extraordinary living artists (including Gillian Wearing, Wolfgang Tillmans, Sarah Jones, Paul Noble and also my now husband, Alessandro Raho).

SC: Could you give us some insight into your responsibilities as Senior Curator of International Art (Performance) at the Tate?

CW: My job involves working on all aspects of the museum: I direct the performance programme, feed into acquisitions for the collection, and collection displays, and spend time organising exhibitions or major commissions. I also write and lecture on the subject of performance within art and art history. At present, I’m working on our annual BMW Tate Live Exhibition with my colleagues Andrea Lissoni and Isabella Maidment, which this year is focused on the pioneering work of the octogenarian American artist Joan Jonas, in dialogue with a number of other artists including Jumana Emil Abboud, Patten, Mark Leckey, and Sylvia Palacios Whitman. I’m also working on the next Hyundai Commission, with the Cuban artist Tania Bruguera. And I’m just finishing a book for Tate Publishing titled Performance in Contemporary Art.

SC: Why is it important that we look at Joan Jonas’ work right now?

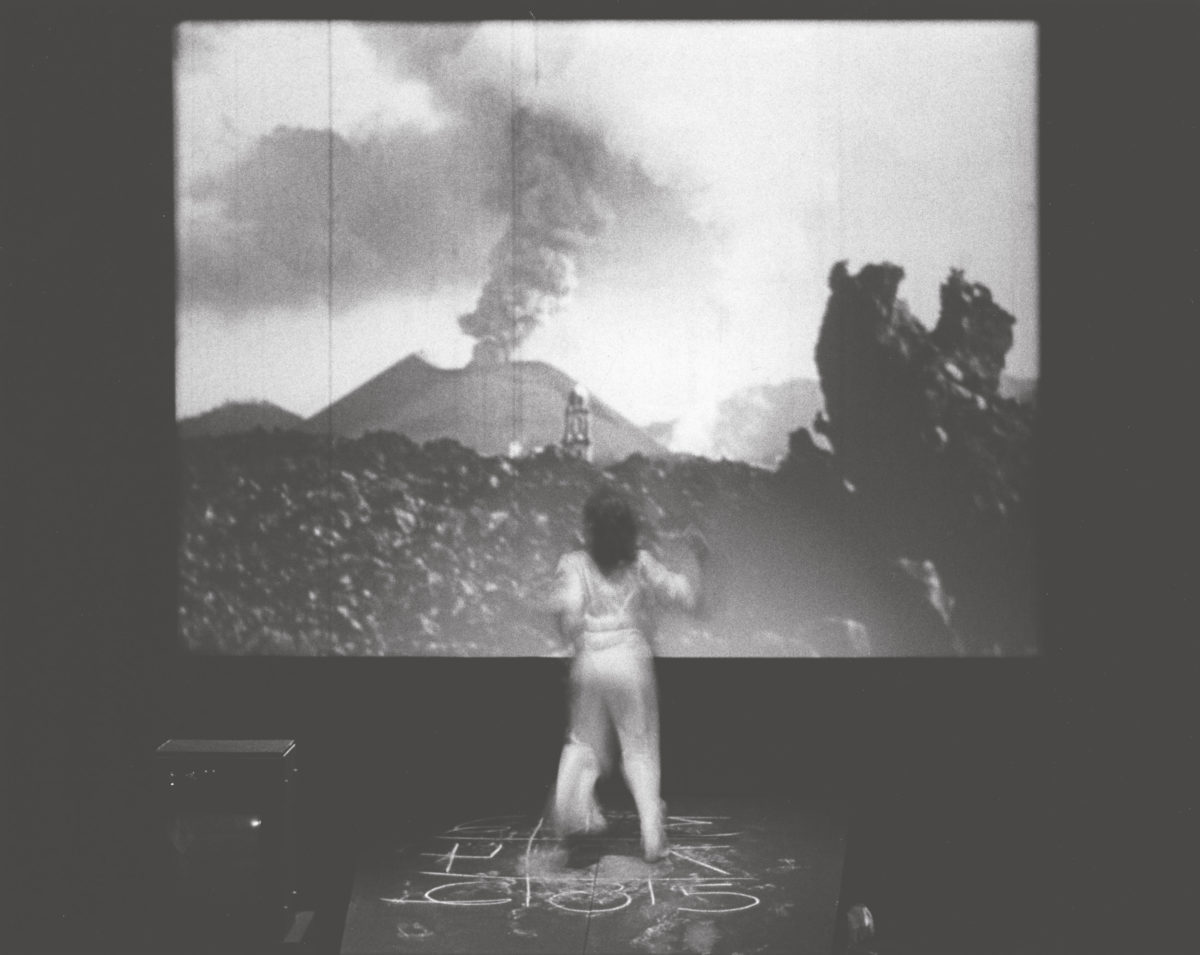

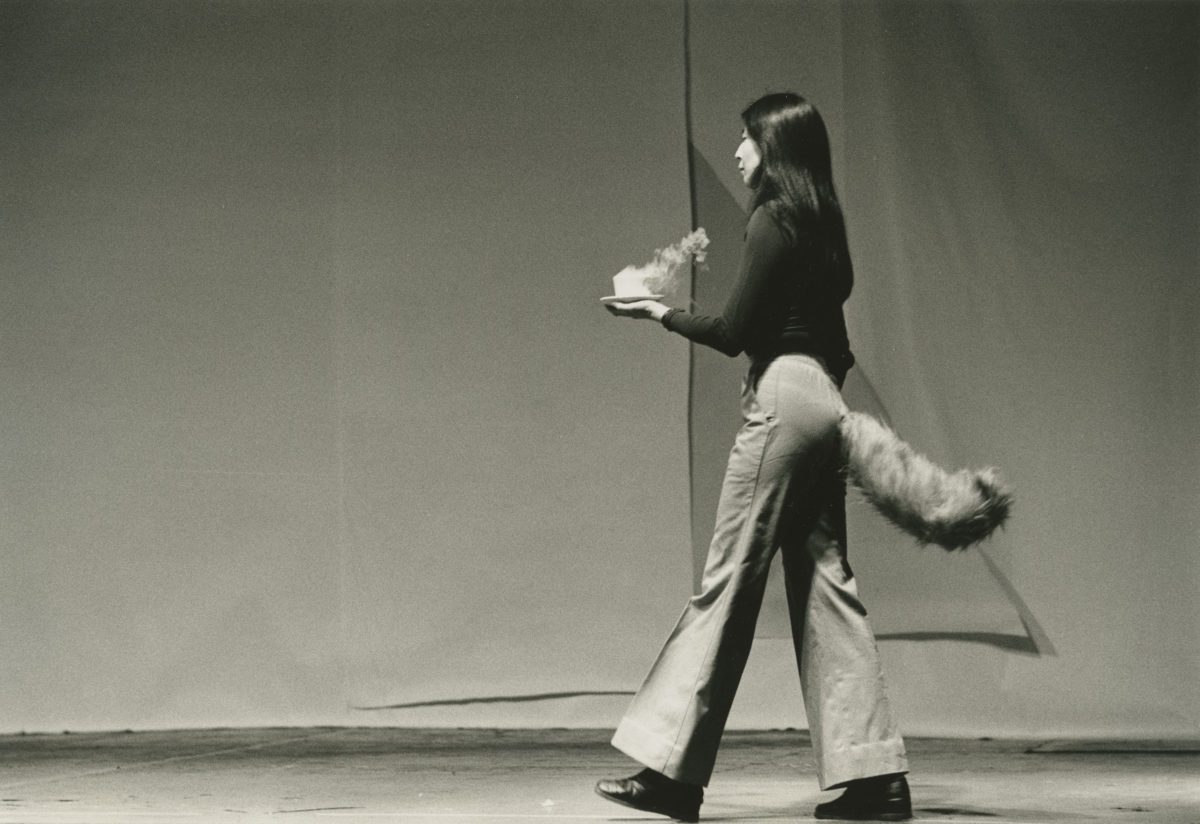

CW: Joan was an early adopter of technology: she bought a portapak camera in Japan in the 1970s, and she understood its implications – the fracturing of present-tense reality – that it signified very early. She would stage her own live performance simultaneously with her mediated image through video onstage. This approach to video mediation, combined with her use of sound ‘delay’ in Delay Delay (1972) and the refraction of the image with mirrors in Mirror Piece II (1970) makes her work prescient in terms of our contemporary experience of reality mediated through smartphone images and screens. She played with this in relation to the malleability of female identity as well: using masks and costumes. At the same time, her work is being shown alongside Picasso, and I have come to think of hers as a kind of temporal cubism: Joan Jonas’s work fractures time, not just the pictorial image as he did.

SC: How did you go about selecting the artists to include; what was the thinking behind showing Jonas’ works alongside intergenerational artists like Mark Leckey and Sylvia Palacios Whitman?

CW: We invited artists whose approaches to performance resonate with Joan: because they, like her, are concerned with rituals that frame the question of sculpture or the object – as Leckey and Palacios Whitman are – or with storytelling, as Jumana Emil Abboud is. Jumana’s work reaches back to an old oral tradition of passing Palestinian fairytales from grandmother to mother to child, and evokes a territory with a stability in this tradition, even if the geographical ground is contested.

SC: Would you say it’s important to have a field of specialism as a curator?

CW: Occasionally I have worried that my specialism (performance) is limiting. But in fact it has been a great guiding principle. The “performance view” on art, which fascinates me, has given me a set of parameters through which I navigate the vast territory of modern and contemporary art across the world. In many ways, it’s simply the embodiment of an attitude about art that says: “this is how we could do things.” Performance is about movement. It demonstrates the provisional nature of culture, and it includes the viewers within the frame. This seems important, both aesthetically and politically. I got interested in the area of art performance through my fascination with artists who transgressed disciplinary boundaries (this began, actually, with a fascination with William Blake’s painted books: neither straight text nor straight painting). But I also always loved dance, and a strong thread in my research interests has been looking at how artists have used dance, choreography, gestures to make images, or initiate participation. What has been especially important for me is that there have been many strong female pioneers in this area. The work of American post-modern choreographer Yvonne Rainer has been a major influence.

SC: Who or what has inspired you during your career?

CW: I have been inspired by the artists I have worked with, especially Yvonne Rainer, and the London artists whose performance I saw early on just as I was starting at Tate and made me want to bring this kind of work into the museum: Mark Leckey and Marvin Gaye Chetwynd, but also performance by Leigh Bowery and the Neo Naturists that I discovered through the choreographer Michael Clark. The history of performance set out by Roselee Goldberg in the 1970s, who now runs the Performa festival in New York, was important to discover. As was the thinking of my MA tutor Briony Fer at UCL.

SC: Could you tell us about your role in initiating the performance programme at the museum back in 2003?

CW: I had been working at the Barbican Centre in the exhibitions department and because of my interest in the cross-disciplinary, I had been keen there to initiate collaborations with other departments – theatre and music – but strangely it was very difficult as despite being a cross-arts centre each department was quite fixed in terms of budgets and spaces. I organised a show called ‘Electric Dreams’ that included Charles Atlas’s film Hail the New Puritans featuring Michael Clark and Leigh Bowery, as I was fascinated by how ‘theatricality’ and drag – forms of artifice associated with night life – might sit in the gallery, which I painted black. For my MA, I had been researching post-modern dance as it related to minimalist sculpture in the USA , and I taught a course about this at Tate Modern. Through that course, I found out that Tate had secured sponsorship funding for a year-long live programme and were looking for a curator.

Ideas were flying around about high profile collaborations between musicians and artists, but I came to the interview with Sheena Wagstaff (then Chief Curator) saying that I did not think we should do ‘gigs in the gallery’, but we should be looking to the emergent interest in performance by younger visual artists, that I could see happening in clubs and artist run spaces in London, and internationally. And that we should find ways to represent the history of performance in our major exhibitions and displays. It was my desire to bring this work into Tate that created a certain momentum. I was lucky in being supported by Sheena and Nick Serota, but it took 10 years for the funding to be established as ‘core programme’, so the performance side of things had had a peripatetic and precarious existence. It has been an extraordinary opportunity to test the ‘elasticity’ of the museum though: each project puts pressure on how we do things in new ways, and changes institutional behaviour a bit. So we are growing by working with artists proposing challenging things.

SC: How critical is the venue in relation to the curation of performance art – in particular, how do The Tanks affect the experience of video and performance works?

CW: We are very fortunate in having the Tanks as they are neither white cube nor black box. A grey zone. This means that they do not determine the ritual for viewing in the way that either of those now conventional art spaces do. Artists can experiment and respond to their unique character. Joan has made beautiful chalk drawings on the wall of one of the tanks which also includes her video installation Reanimation. The drawings resemble large cave paintings, which totally make sense in these underground spaces. At the same time, the round spaces lend themselves beautifully to ritual gathering in a circle. It has been amazing to work with a number of different artists in the spaces since we opened them and to learn the space through their imaginations, and their eyes. We feel the Tanks – building on their historic industrial function – can represent a kind of ‘generator’ space that shakes the basement, fuels the museum.

SC: Can you tell us a little about the daily performances planned for the Bankside’s shoreline during the programme?

CW: This is a piece called Delay Delay that was made in NY and then on the banks of the Tiber in Rome in the early 1970s. Joan has worked in London with a fantastic group of younger artist and performers, directed by her associate Nefeli Skarmea, to re-make the piece, according to a recomposed score. They wear white costumes and try to communicate with each other using the clapping of wooden blocks, megaphones and sculptural objects and flags, across the river. It’s beautiful and poignant, and seeing the younger generation inhabit this important historical work by Joan offers a whole new perspective on how to share art history in a museum. It’s also wonderful how the intervention into the river landscape animates it as a picture view – with a passing audience, and the interruption of passing boats too.

SC: How do you hope the BMW Tate Live Exhibition will evolve in years to come?

CW: It’s fantastic to have this regular slot to experiment with the live exhibition format for the next 3 years, and to have funding from BMW secured. The unique nature of it is that it’s neither festival nor exhibition, but rather a hybrid situation in which artists can work through both space and time. We try to follow artists’ practices and bring it to our audiences in ways that are as closely aligned with the artists’ vision as possible.

SC: What are your exhibition highlights for 2018 – at the Tate or elsewhere?

CW: I’m looking forward to seeing Paul Maheke at the Chisenhale in April – he was in the live exhibition with a piece called Mbu last year. Block Universe are preparing an exciting festival this year in different venues, with great artists including Maria Hassabi and Jamila Johnson Small. And I’m looking forward to Emily Roysdon’s show at Studio Voltaire (where I am a trustee).

SC: Which London-based curators do you think are doing something particularly interesting right now?

CW: Stefan Kalmar is reinventing the ICA in exciting ways; Emily Pethick does a fantastic programme at the Showroom. For performance, I have been following the programme of Kunstraum in the East end with great interest, and I look forward to Vincent Honoré and Cédric Fauq’s Baltic Triennial.

SC: What makes the Tate unique as an arts institution?

CW: Tate Modern is a relatively young museum and it has a young spirit, with amazing staff, so instead of saying ‘we don’t do things like that’, there is a willingness to experiment and try things, combined with colleagues who have real dedication and excellence. It is also great to have a female director of Tate Modern, Frances Morris, who pushed through the showing of 50/50 men and women in our opening displays in 2016, and has driven a global agenda for collecting. There is more work to do, but these things have been a good start.

SC: Are you able to tell us about any upcoming projects?

CW: My next big project is working with the Cuban artist and activist, inventor of ‘arte util’ (useful art) Tania Bruguera for the 2018 Hyundai Commission in the Turbine Hall. I can’t say yet what she will be doing, but it’s thrilling to work with her and important at this uncertain political time to have her fierce political thinking to challenge us. Her Tate collection work, Tatlin’s Whisper 5 is the piece involving the Metropolitan mounted police who perform crowd control exercises in the gallery.

SC: What are you currently reading?

CW: The Invention of Morel, 1940, by the Argentinian writer Adolfo Bioy Casares: a book recommended by two artists I’ve been working with: Mark Leckey and Alexandra Pirici. It’s about hallucination, and love and solipsism, but relates to their respective interests in technology, virtual reality and the hologram.

SC: Where do you enjoy spending time outside of work?

CW: I live in Hastings with my family so I enjoy the beach at weekends with my kids, and am addicted to sea swimming when it’s a little warmer!

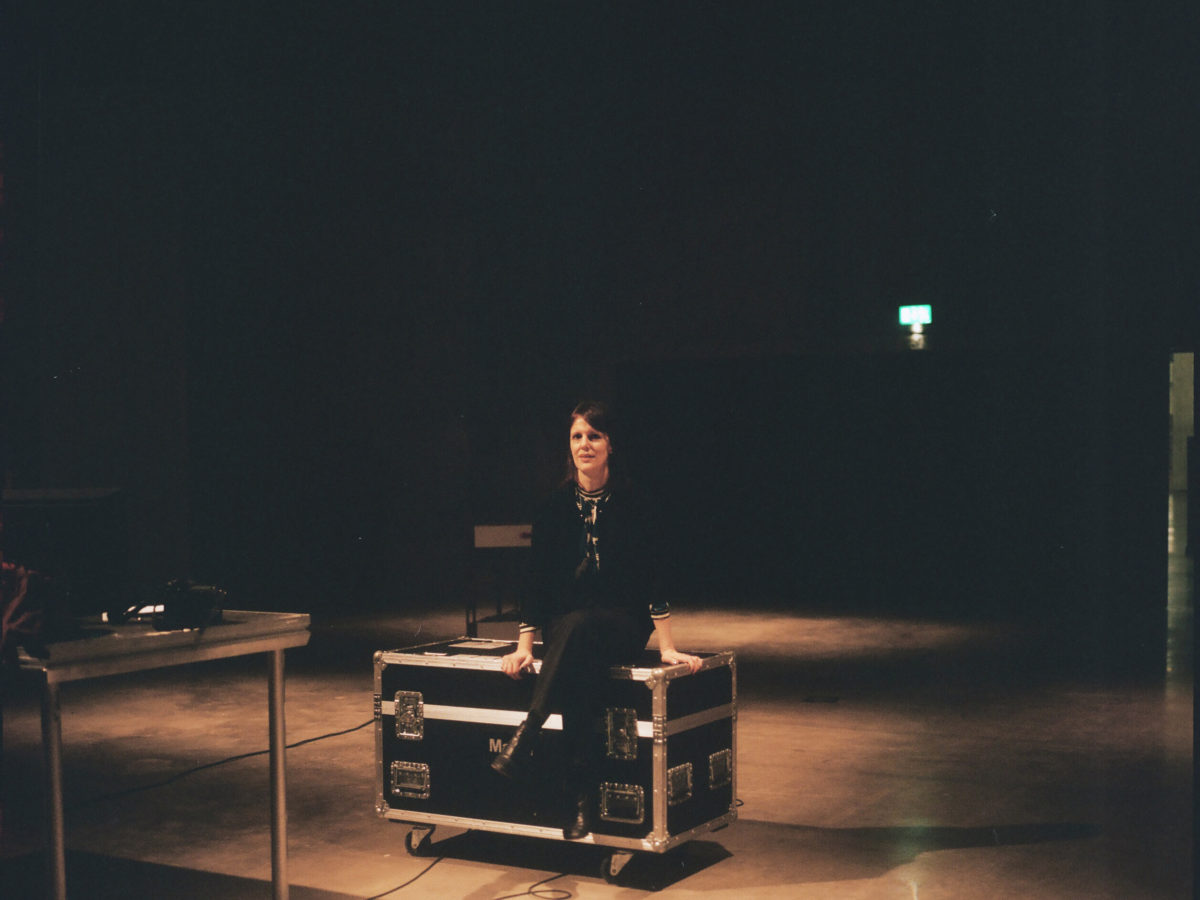

Interview by Keshav Anand | Photography by Ana Cuba