Cultural Representation & Eating Out

By Keshav AnandBritain’s love for “Indian food” was perhaps epitomised when the Foreign Secretary Robin Cook named chicken tikka masala a British national dish in 2001, highlighting the omnipresence of foreign influences. Interestingly, the dish, comprising chunks of roasted marinated chicken in a spiced sauce, is “a dish which does not exist in Indian cuisine,” journalist Amit Roy points out. London restaurateur Amin Ali, founder of The Red Fort, remembers serving the dish when he first arrived in London in the early 70’s, as a waiter, perplexed by what it was. Cementing its place as a household regular, chicken tikka masala was introduced to supermarkets by G.K. Noon in 1983, and by the end of the millennium it was widely regarded as Britain’s most popular single dish.

When the dish is referred to, it’s commonly recognised as Indian food, certainly within the context of the UK, though its origins remain clouded. The process of borrowing and adapting to suit local tastes, over the course of decades or centuries, forges new faux cultures, ones that offer potentials for invention, but also often reinforce stereotypes about food, and broadly culture, that might not have originally even existed. This generating and perpetuating of faux culture, through enduring appropriation, works like powerful branding. With the case of chicken tikka masala in mind, it’s interesting to consider the broad impact of the restaurant industry on our comprehension of world foods.

In an article that went viral back in 2015, journalist Rachel Kuo observed: “When a dominant culture reduces another community to its cuisine, subsumes histories and stories into menu items – when people think culture can seemingly be understood with a bite of food, that’s where it gets problematic.”

Given that food is a critical part of culture, intrinsically linked with people’s lives and even, to an extent, their understanding of themselves and others, it is hard to treat cooking as a detached art form, separate from human beings and human lives. It is true that authenticity, in the sense of something being as close to the original as possible, does not need to be a priority for making delicious food; although when certain fusion endeavours attempt to be entirely culturally agnostic, pulling from diverse influences with no acknowledgment, of course the food can still taste good, but there is a vacuity, and perhaps for some, condescension in the experience.

Inevitably, when bringing a foreign experience into a new context, there has to be some element of streamlining. Finding a way to create a sense of genuineness while fulfilling practicalities, without being overly reductive or insensitive can be a tricky task. There’s something to be said about cultural ownership too; when someone manipulates the food of their own heritage, there is often more tolerance to it. Perhaps the hardest task then is to take on the influence of a culture that is not your own, and bring it into a new context without messing up – but there are potential opportunities for this to be done successfully.

Food studies scholar Massimo Montanari posits, in his book Food Is Culture: ““To eat geographically,” to know or express a culture of a specific region through cuisine, local produce, products, recipes, seems to us absolutely “natural” … But this well-established commonplace, even cliché, according to which the cuisine of a region would be an ancient, indigenous, atavistic reality, is based on a misunderstanding, one deserving a pause for serious consideration. First of all, we ought to distinguish between produce and dishes (the individual recipes) on one hand, and on the other, cuisine (understood as an ensemble of dishes and of rules). Local dishes linked to local produce clearly have always existed. From this point of view, all food is by definition “local,” that is, of the region …”

Reflecting on the notion of all food being “local,” at least in some sense, by consequence of the origins of ingredients, recreating anything in a disparate geographical context becomes a reinterpretation, something new. London restaurant Kricket, founded by Will Bowlby and Rik Campbell, takes it’s inspiration from Indian cooking, but in a way that avoids becoming a pastiche. Acknowledging traditions while working with typically British produce, such as rabbit and samphire, the menu, and for that matter the interior, do not attempt to plagiarise but rather propose a dialogue between cultures, whilst offering due credit. Perhaps it is in its open acknowledgement of being inspired by Indian cooking, as oppose to asserting itself as Indian cuisine, or worse, an “elevated” version, that makes the concept work.

Design firm, Run For The Hills, who created Kricket’s interiors, told Something Curated: “We have always tried to be subtle and original in our Indian inspired detailing to steer clear of pastiche, so many of our vintage finds and props aren’t there for purely decorative purposes, we have given them a practical function. From vintage propellers turned into candle sticks to Indian clock boxes repurposed into discreetly branded lighting, sitting on shelves nestled amongst spirit bottles and glassware … In the basement of Soho, our in-house graphic artists teamed up with British Indian fine artist Natasha Kumar to create a special wallpaper in the private dining booth.”

The majority of London’s food offering fits into a handful of categories, highlighted by food delivery apps for easy consumption. This template can mean broader territories, beside it seems the all-encompassing Pan-Asian, become tricky to market, which might explain the repetitive patterns we see proliferate. In saying this, there are of course exceptions, as certain establishments decidedly explore more expansive terrains, as well as little known and very specific regions. South London’s Peckham Bazaar, for example, traverses the Balkans, naturally oscillating between Albanian, Turkish, Greek and Iranian cuisine, among other influences.

https://www.instagram.com/p/BbmVN9rnDV9/?hl=en&taken-by=peckhambazaar

Founder John Gionleka told us: “Peckham Bazaar came about partly because of the civilising forces, the plagiarising and appropriating of cultures in Europe which are going unrepresented. The challenge of course being, when you are plagiarised or appropriated you have no say over how the material is represented. In the context of the Balkans, it has always been the case. In terms of food, the Balkans is not different to London. People come and go; influences came from many sectors and many parts of the world. The affinity that people have with good food and good life is obvious; it’s a case of showcasing something to a public that is savvy enough to gauge quality when they see it.”

While Rachel Kuo asserts that culture cannot be “understood with a bite of food,” food does, or at least can, provide somewhat of a window into another way of life, offering insight, even if limited, into the sustenance of diverse peoples. Perhaps the contention highlighted in her point, is more to do with people feeling an unjustified sense of entitlement over a culture based on their sampling of a bastardised cuisine, as oppose to denying food’s role in defining culture. Beyond the food, there are other key elements that comprise the experience of eating, and certainly eating out. Packaging and presenting culture in a way that is marketable, consumable and ultimately enjoyable, within the context of dining, is a nuanced task, and one that is easily faulted.

Expanding on what “bringing a Portuguese experience to London” entails for him, restaurateur Marco Mendes, founder of newly opened Algarvian restaurant Casa do Frango in London Bridge, told us: “The Algarve has it’s own strong culinary identity, and I wanted to bring, I suppose, my nostalgia, my memories and experiences to London in the form of a restaurant. For me, it represents family, friends – a casual form of dining which is very inclusive and jovial … Our branding colours were inspired by Portuguese oranges. The interior is influenced by Algarvian landscapes; it very much looks like a restaurant there, complete with the arching windows. The style is almost transporting guests to Portugal, or certainly outside of London.”

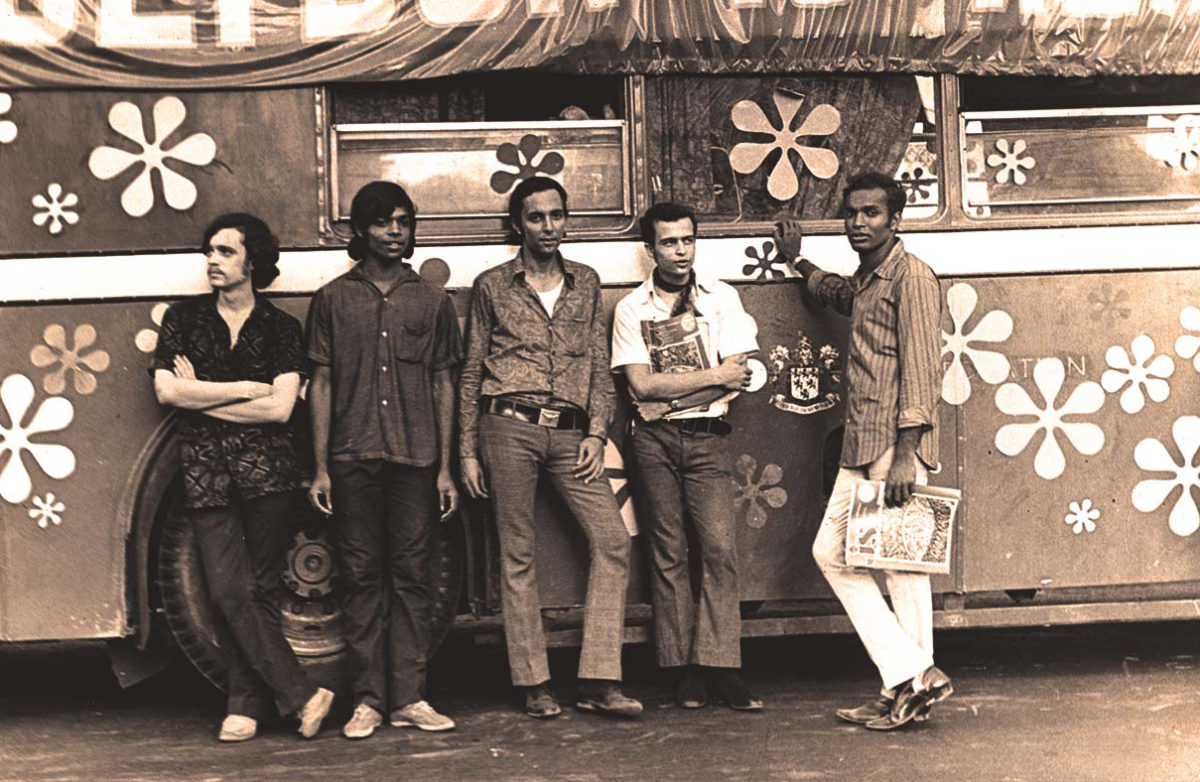

Dishoom’s co-founder Shamil Thakrar explained to Something Curated: “When we create a Dishoom, we always imagine it as an Irani café deeply rooted in some aspect of Bombay history. For example, in Carnaby, the setting is Bombay’s rock scene, which flared up briefly in the 1960s and 1970s. In King’s Cross, the setting is in a notional go-down (or warehouse) near Victoria Terminus, the Independence movement a backdrop. We then sit down and write a story – a different founding myth – for each Dishoom. The creative of each café is based on this founding myth. Literally every single aspect of the design (no detail too small) is informed by it. We spend weeks and months researching the Bombay of the period. We visit the original, remaining Irani cafés and meet people with memories of the period. We comb the city for the right antique furniture, researching in libraries, archives, homes, museums, derelict warehouses, railway offices, and whatever else the story calls for… This (hopefully) all comes together within the walls of the restaurant to create a different and maybe even somewhat immersive world.”

As highlighted in these insights, the immersive and transportive quality that a dining experience can offer goes far beyond the food being served, expanding to all aspects of representation, from décor and tableware, to uniforms and graphic design. “Ultimately, restaurants are very much about the way they make you feel and that’s all part of the journey and story you are taking your guests on when they walk through your doors,” Laura Harper Hinton, co-founder of Caravan Restaurants, told us. Perhaps it’s not farfetched then to compare the production of a restaurant to that of a film; the storyline, the sets, the lighting, the props, the actors, or the restaurant staff, all come together to form a considered and meticulously engineered experience.

According to food scholar, Nicola Perullo, even the names of dishes and their descriptions on a menu play an important role in our experience of dining, and by extension, our perception of a cuisine. “I would be lying if I said my teeth didn’t clench every time someone ordered a “chai tea” (a “tea tea”) or a “naan bread” (a “bread bread”),” admits journalist Shreeta Lakhani. With an experience that is so largely reliant on our most visceral senses, taste, smell and sight, it’s curious to consider the impact of language, something that is relatively abstract and constructed, on our understanding of food. Words offer a powerful means of representation, most often acting as our main point of reference when selecting a dish from a menu. In his book Taste As Experience, Perullo writes: “A name or a word may produce – or bypass – the taste of food because words have to do with the mouth. Words and writing condense taste and image into the imaginary.”

In many ways, creating a restaurant is like writing a romanticised fiction based on real life events. And from the perspective of a diner, perhaps that is one of the great joys of eating out – not having to deal with complete realities, with all their adversities. And like stories, sometimes it works well, and sometimes it feels overly reductive. The act of eating is an equaliser, a democratising need that we must all engage in in some form and context, and by virtue of this, food can operate as a cultural bridge, offering insight, even if not true understanding, into varied cultures. Perhaps the danger lies in not recognising the myth that has been created for our enjoyment, and taking it as truth. That is not to say food and restaurants cannot or do not offer any aspect of authenticity, but ultimately no culture can be justly packaged in a singular platform.

Words by Keshav Anand | Feature image via Pinterest