The Pervading Influence Of Donald Judd

By Something CuratedBorn in Excelsior Springs, Missouri, American artist Donald Judd is best known for his large-scale and decidedly unadorned sculptures made throughout the mid-to-late twentieth century. Judd earned a degree in Philosophy from Columbia University, while simultaneously taking night courses at the Art Students League of New York. He supported himself by writing art criticism pieces for popular magazines, such as ARTNews and Arts Magazine, reviewing the work of over 500 artists. In 1968, he bought a five-story building on Spring Street in New York to serve as his studio and residence, where he created some of his most influential works and developed his concept of permanent installation. Judd’s rejection of traditional sculpture and painting led him to a conception of art built around the idea of the object as it exists in the environment. His legacy still prevails today, acting as an important reference point for many artists and designers alike.

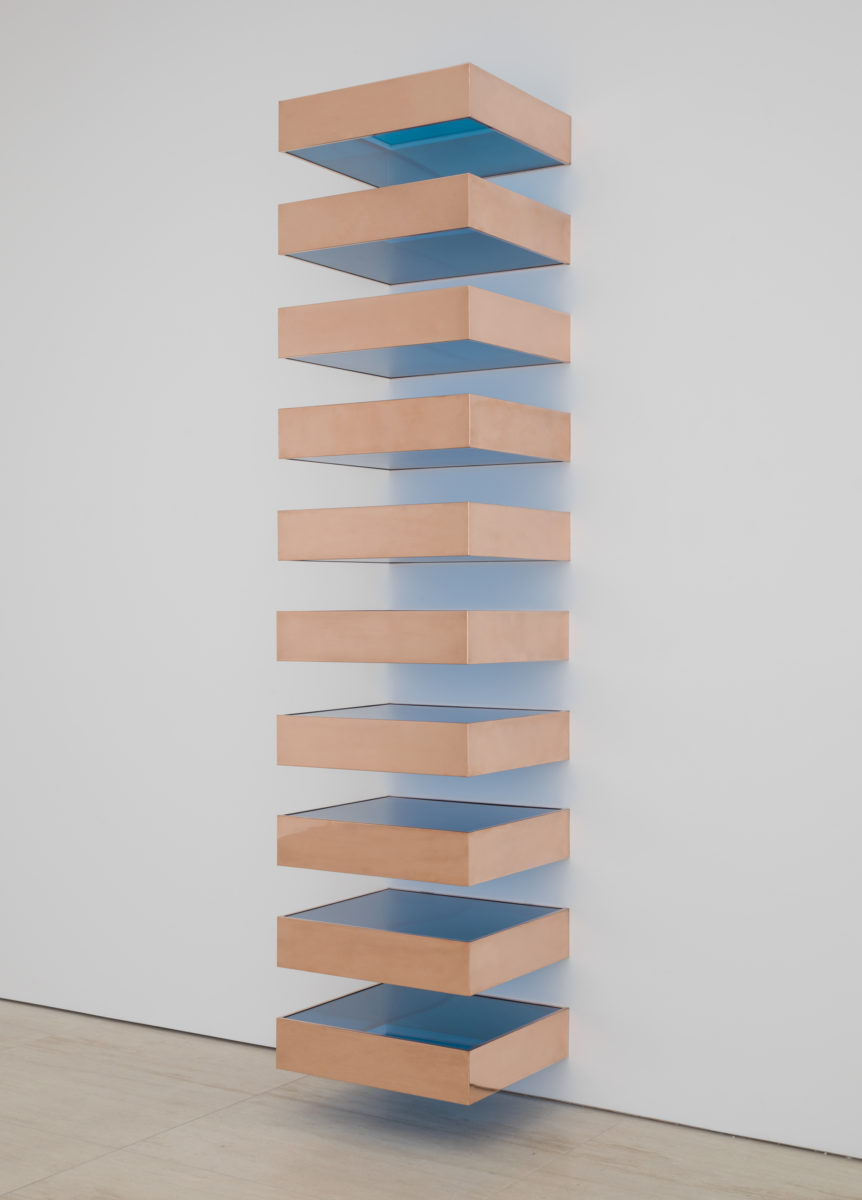

Dina Amin, Head of 20th Century and Contemporary Art, Europe, at Phillips told Something Curated: “Judd’s iconic boxes, stacks and progressions fundamentally redefined one’s rapport to space, creating an entirely new experience of one’s surroundings. Judd’s reduction of form allowed a fresh perspective on the limitations of traditional media and opened up a conversation on three-dimensionality. As such, he’s one of the key, trailblazing figures to have introduced ‘pure forms’ to art. Although he disliked the term, he was one of the great precursors of Minimalism and the many associated movements and trends that followed.”

Traditionally, the work of the Minimalist movement aimed to put an end to the art of the Abstract Expressionist’s reliance on the self-referential element of the painter in order to form pieces that were free from emotion. Judd applied this idea to his work quite seriously, and created sculptures that were comprised of single or repeated geometric shapes produced from materials that avoided using the artist’s personal touch. Judd’s pieces were simplistic yet inventive, and inspired a new kind of design style. He made objects that stood on their own as part of a broadened field of image making, and that did not allude to anything beyond their own physical presence. Judd used a variety of colours in his artwork, ranging from bright, primary yellows and reds to muted greys and intense blacks.

“Judd’s forms are geometric; his materials are industrial and readily available (anodised aluminium, plywood, Plexiglas are among his most used),” Amin tells us. She continues: “Instead of following traditional definitions of sculpture, which he felt was too limiting as a medium, Judd sought three-dimensionality. By giving matter clean, simple forms, and building upon unassuming materials, Judd allowed his work to be more open, like anthropomorphic objects engaging with space organically. The forms and materials he used allowed for this unique vision to materialise, and the artist’s signature use of repetition and multiplication in his work rendered his objects all-the-more inviting and democratic.”

In 1971, Judd paid a visit to Marfa, Texas, and bought a property there two years later. The everyday realities of this town appealed to Judd, as he wanted to escape the harshness of the New York art scene. Marfa was where he would open and found The Chinati Foundation, which proved to be an imperative moment in his life and career. In 1979, he acquired Fort D.A. Russell, which was a compound of decommissioned military buildings spanning over 340 acres of land. Judd transformed these buildings into a permanent space to showcase both his work and the work of other artists, such as Carl Andre and Dan Flavin, in a non-museum space. All works have an emphasis on how art and the surrounding landscape can be inextricably linked. The space opened as The Chinati Foundation in 1986, and now serves as a contemporary art museum with over 100 of his works on display. In a mission statement for the Chinati Foundation, he wrote, “The art and architecture of the past that we know is that which remains. The best is that which remains where it was painted, placed or built. Most of the art of the past that could be moved was taken by conquerors.”

Judd died on 12 February 1994, but his influence does not end there. “Judd’s approach was really radical and clear: he wrote about what art should and shouldn’t be, what ‘worked’ and what didn’t,” says Amin, “His practice continues to be influential today, precisely because it seeks to achieve such unequivocal honesty. This is something that artists and designers alike have continuously tried to accomplish: create their own visual lexicon, produce something new, true, and transcending. Because Judd’s art from the mid-1960s onwards was primarily made of industrial materials, his ‘pure forms’ were often reminiscent of industrial design; the fact that his boxes, stacks and progressions extended from the wall or rose from the ground further likened them to living companions inhabiting space. This is an idea that has tremendously excited later generations of creatives, and further encouraged artists to explore the cross between art and design.”

Today, Judd’s work is continually exhibited, showing across institutions and galleries such as The Guggenheim, MoMA, Tate and David Zwirner, in recent times, among many others. His former residence and private working space on 101 Spring Street has become a veritable museum, where small groups of guests can take guided tours of the five-story building throughout the week. It is preserved by the Judd Foundation, whose aim is to promote a wider understanding of Judd’s artistic legacy by providing access to his former spaces in New York and Marfa.

Words by Jane Herz | Feature image: Donald Judd by Arnold Newman. Gelatin silver print. Gift of Gary Davis. (via MoMA)