Interview: Mark Godfrey On Curating Franz West’s New Retrospective At Tate Modern

By Keshav AnandFranz West brought a defiant vision into the pristine spaces of art galleries. His abstract sculptures, furniture, collages and large-scale works are direct and unpretentious. Born in Vienna, West collaborated with numerous artists, musicians, writers and photographers throughout his career. Opening tomorrow, 20 February, and running until 2 June 2019, at Tate Modern, Franz West, a major retrospective curated by Mark Godfrey, comprises almost 200 works including abstract sculptures, furniture, collages and monumental outdoor pieces. In the run up to the show’s opening, Godfrey, who has been responsible for curating a number of the Tate’s most popular shows over the past decade, spoke with Something Curated.

Something Curated: Could you give us some insight into your responsibilities as Senior Curator, International Art (Europe and the Americas) at Tate Modern?

Mark Godfrey: My job is made up of three parts – I curate major temporary exhibitions, and I’ve been doing this for about 11 years now; I’ve done exhibitions with Roni Horn, Francis Alÿs, Gerhard Richter, Sigmar Polke, Alighiero Boetti, and more recently Richard Hamilton, and I’m currently working on the Franz West and Olafur Eliasson shows. Each of these projects involved thinking about how to present a story in a space in a way that’s compelling and beautiful to look at. Another part of the job is working on the collection, and that means identifying what art we want to acquire and how we acquire it, working closely with patrons and artists. Thirdly, I work with artworks that are in the permanent collection, to display them to the public.

SC: Can you talk to us about your journey into the art world? Was curation something you’d always had an interest in pursuing?

MG: It was. Ever since I was a kid I used to go to art exhibitions, and then I studied Art History for my masters and PHD. For many years I was teaching Art History at the Slade School of Fine Art, where my students were artists, and I began to do a few little curated shows as external projects, and it was at that point that I thought that what I really wanted to do was make exhibitions with artists, more than teaching at a university and so I applied for a job at the Tate. I never did a curating course; I’ve kind of learnt that on the job. But it came from art history and a desire to work with artists and objects.

SC: Would you say it’s important to have a field of specialism as a curator?

MG: Yes, definitely. Although I would also say that you should be open to learning about new fields beyond your specialism. So for instance, I came to the subject knowing a lot about a particular area of 1960s and 1970s art in America, and knew nothing about African American art of that period but I wasn’t afraid to learn for our exhibition, Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power. It’s great to have an area of expertise but I would caution against just sticking to that area because I think people can teach themselves new things all the time.

Steel, extruded polystyrene, gauze, paint and wood, sculpture

Franz West Privatstiftung

© Estate Franz West, © Archiv Franz West

SC: What are you aiming to achieve with the upcoming Franz West exhibition?

MG: We want to show how fantastic an artist he was and how influential he continues to be. He was a very irreverent artist with a radical approach to sculpture and furniture, as well as collage and mixed media. He created a type of sculpture that you can lounge around on, look at, or play with. The conventions of the art world were ones that he was continually ready to challenge. When people looked down on papier mâché, he made sculptures from papier mâché. He created art that people could touch or sit down on; there was an extraordinary generosity in his work as well and a great degree of fun that becomes more apparent as he moved towards the final years of his life.

SC: Why is West an important artist for us to consider now?

MG: As the art world becomes increasingly professionalised, a lot of artists are very concerned with things like making their own website, thinking a lot about what it means to work within an economic structure, or their situation on Instagram and so on – I think West is a great reminder of a model of art practice that really is about flouting all the rules. It’s about a combination of absolute fun and a deep concern with philosophy, a great passion of his. In an environment that’s increasingly about administration, he’s a different and important example of what an artist could be.

SC: I understand the show is set to present almost 200 works, including sculpture, drawing, photography, and writing – could you tell us about your approach to displaying these diverse elements?

MG: We wanted to capture the spirit of Franz West, even though he has passed away. Rather than having a clinical arrangement with white walls and so on, we wanted something that was going to feel a bit more open, and also respond to the architecture in which we are showing the work, which is the Blavatnik Building at Tate Modern. With all that in mind, I approached Sarah Lucas; she had worked with West several times when he was alive and I asked her to help with the display concept for the show.

Medium Papier mâché, extruded polystyrene, epoxy resin, synthetic enamel paint, metal

Courtesy Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Zurich / New York

She wasn’t involved in selecting works or in deciding where works were going to be – her input came when we were thinking about the walls, the stanchions and the pedestals, which were very important to West. She had a lot of great ideas for all of this, including walls that are made of concrete boards and MDF, pedestals that are made of breezeblocks, and painted stanchions using colours Franz West used to use. So the experience as you’re going around the show is quite wrapped up with Sarah’s contribution. The space feels very open, and we’ve also use enormous, billboard sized images of some of his outside works to give a sense of outdoor work even inside.

SC: What was the thinking behind including other artists and collaborators, such as Paul McCarthy and Heimo Zobernig, in the show?

MG: Franz West collaborated all his life, and he did so in various ways. One of the ways was to work with another artist on a piece which was simply co-authored. For instance, he made several works with the Austrian painter Herbert Brandl, as well as with Heimo Zobernig; and when these works were shown, they were credited to both collaborating artists. And we have works like that in the exhibition. Then there was another model of collaboration where he would trade works with his friends, by his friends, and include these works in constellations or installations that he would then make. So there is some work in the show that includes objects by him, along with an array of framed drawings by people like Paul McCarthy and Raymond Pettibon, among others.

SC: Could you tell us more about what West described as his ‘Adaptives’?

MG: The ‘Adaptives’ were begun in the 70s but only named in 1981. They were usually white objects which were made of plaster or papier mâché, over everyday objects like a paintbrush or another sort of implement. His idea was that people should freely handle them, and the way people interacted with the objects would indicate the psychology of the user. While they’re very fun, he also believed they would in some way reveal something of your neurosis. He also made films of people using them. It’s quite a playful approach to sculpture with an underlying seriousness about how the objects function as an extension of the body.

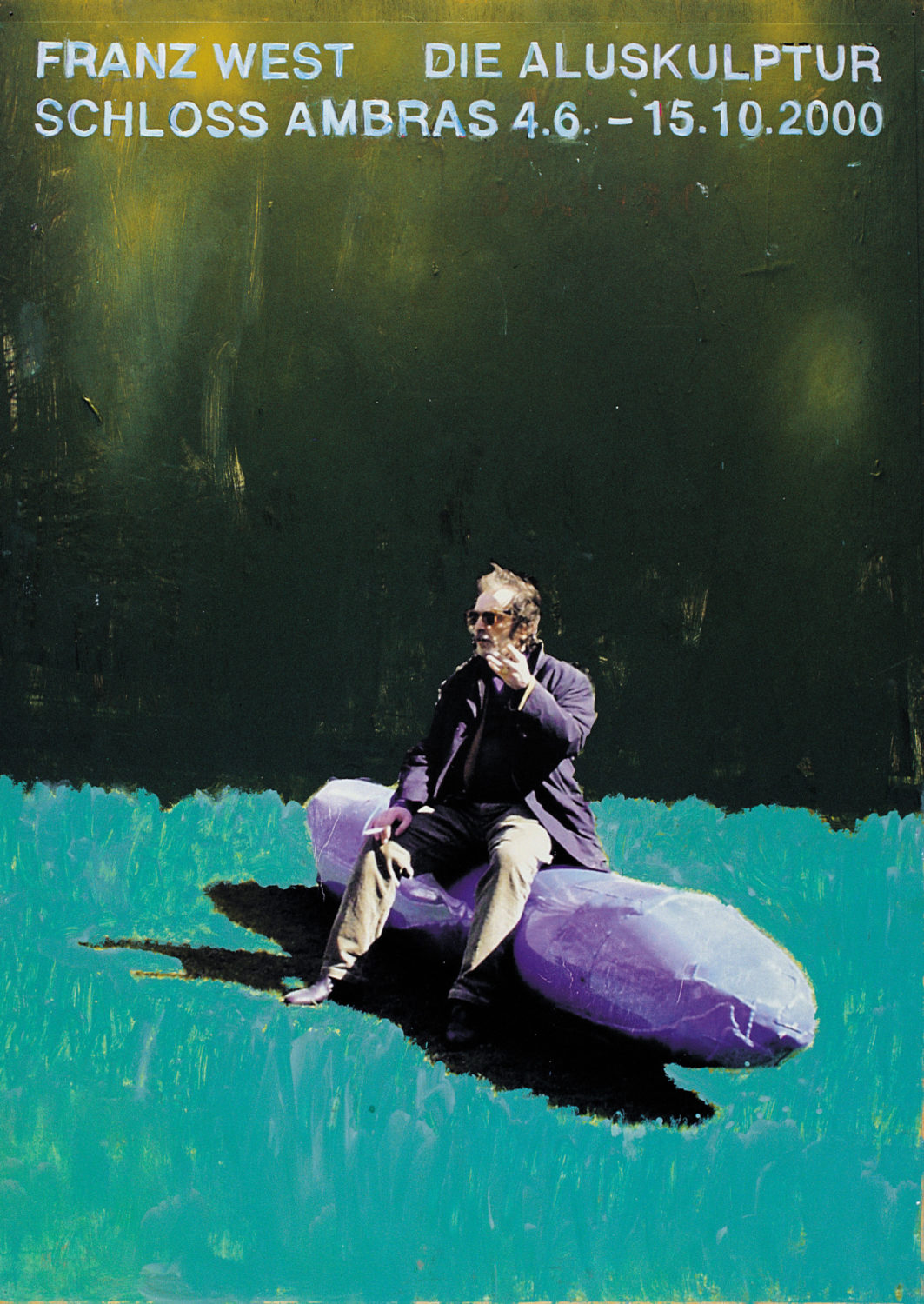

Collage, gouache and offset printing on chipboard Dimensions 860 x 615 mm

Franz West Privatstiftung/Estate Franz West, Vienna

© Estate Franz West, © Archiv Franz West

SC: Is there a piece of work that you are particularly excited to be able to include?

MG: There is a work that wasn’t included in the recent Centre Pompidou show, called Schandflugel, which is a giant golden sculpture, the largest he made in the 1980s, and really a premonition of the scale of his later work. It’s over three meters high and it’s painted gold, and it’s a very peculiar triangular shape that was based on the shape of a club, as in the weapon, held by Hercules. That work was included prominently in an exhibition that West had in 1987 in Vienna but since hasn’t been seen much; and it was owned by the artist Günther Förg, who was a friend of West’s. We installed it this morning and I’m really pleased to see it at the gallery.

SC: Which curators do you think are doing something particularly interesting right now in London or elsewhere?

MG: I have massive respect for my colleagues and I’m naturally closest to them and think their work is really interesting – Catherine Wood and her approach to performance, and what she’s about to do with Anne Imhof; or my colleague Andrea Lissoni and his work with film programme at Tate. Outside of the gallery, Scott Rothkopf, who is one of the directors at the Whitney Museum, is someone whose approach to installing art I particularly admire. I think he often makes tiny tweaks in installation that make the work even more interesting that you thought it was before you see a show. To me that’s really one of the marks of interesting curating, when the curating has thought not just about an academic argument but how to present the work very well within the given architecture.

SC: What are you currently reading?

MG: Lisa Halliday’s book Asymmetry.

Franz West at Tate Modern, Bankside, London SE1 9TG| 20 February – 2 June 2019

Interview by Keshav Anand | Feature image: Rrose/ Drama, 2001. Lacquered aluminium. Telenor Art Collection, Courtesy Peder Lund © Estate Franz West, © Archiv Franz West