A To Z Guide Of The Whitney Biennial 2019

By Something CuratedThe Whitney Biennial, running at the Whitney Museum until 22 September 2019, is a seminal event for anyone interested in finding out what’s happening in art today. Curators Jane Panetta and Rujeko Hockley have been visiting artists over the past year in search of the most progressive and relevant work. Featuring seventy-five artists and collectives working in painting, sculpture, installation, film and video, photography, performance, and sound, the 2019 Biennial takes the pulse of the contemporary artistic moment. Introduced by the Museum’s founder Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney in 1932, the Biennial is the longest-running exhibition in the country to chart the latest developments in American art.

Expanding on key issues and approaches emerging across this year’s exhibition, curators Panetta and Hockley note: “The mining of history as a means to reimagine the present or future; a profound consideration of race, gender, and equity; and explorations of the vulnerability of the body. Concerns for community appear in the content and social engagement of the work and also in the ways that the artists navigate the world. Many of the artists included emphasise the physicality of their materials, whether in sculptures assembled out of found objects, heavily worked paintings, or painstakingly detailed drawings.” Taking a closer look at this year’s show, Something Curated highlights eight of the most exciting artists included in the Whitney Biennial 2019.

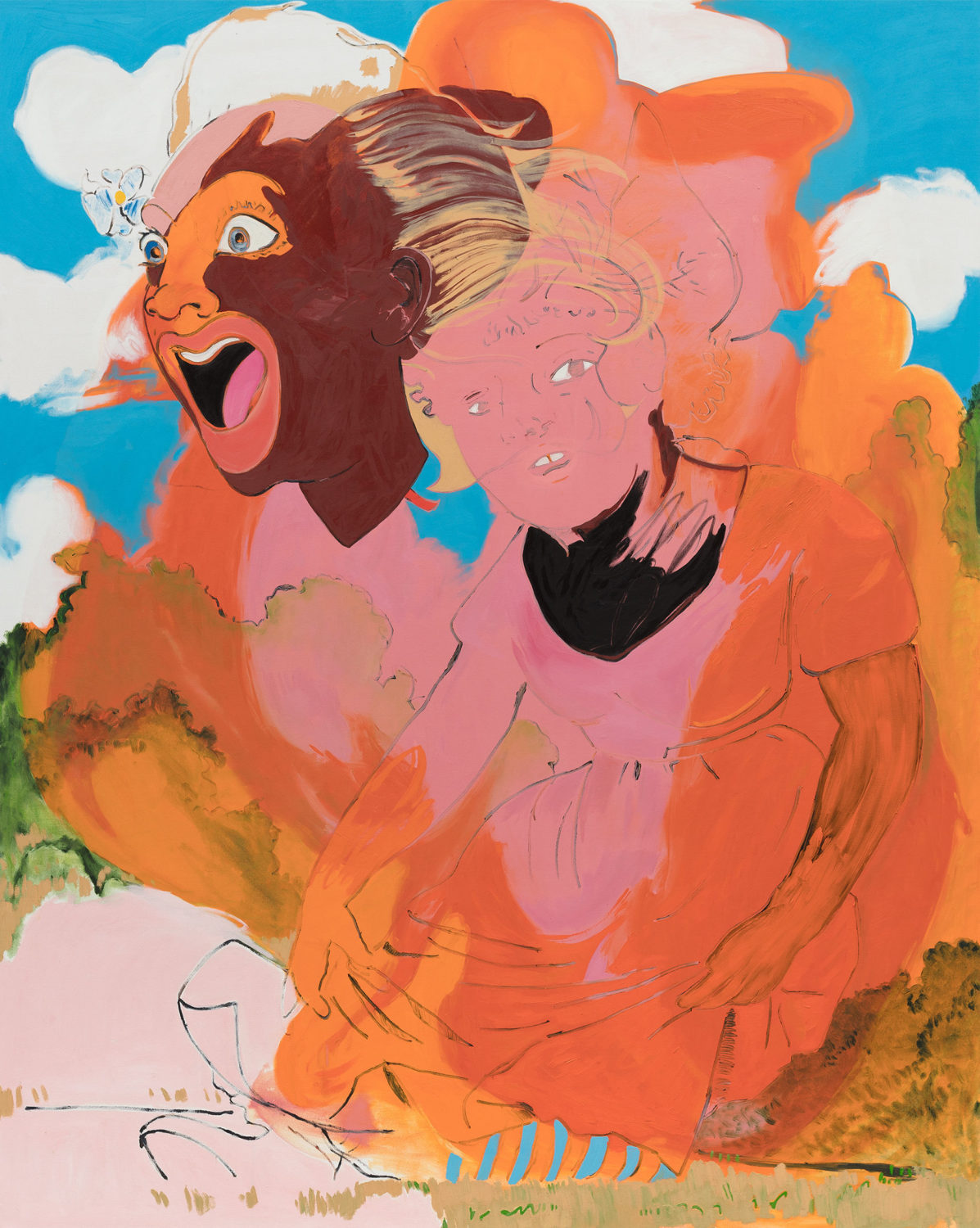

Thrill Issues, 2017 || Janiva Ellis

In her paintings, Janiva Ellis makes pointed use of humour, repurposing imagery from popular media and art that informed her youth, appropriating animated characters that often represent underlying tension in her paintings’ narratives. In the foreground of the hybrid landscape presented in the Biennial, a mysterious scene unfolds in which a graphically rendered figure guards a morphing cartoon that is carefully blended together from multiple applications of paint. Simultaneously projecting determination, amusement, and stress, the forms are exaggerated yet dwarfed by the vastness of the landscape.

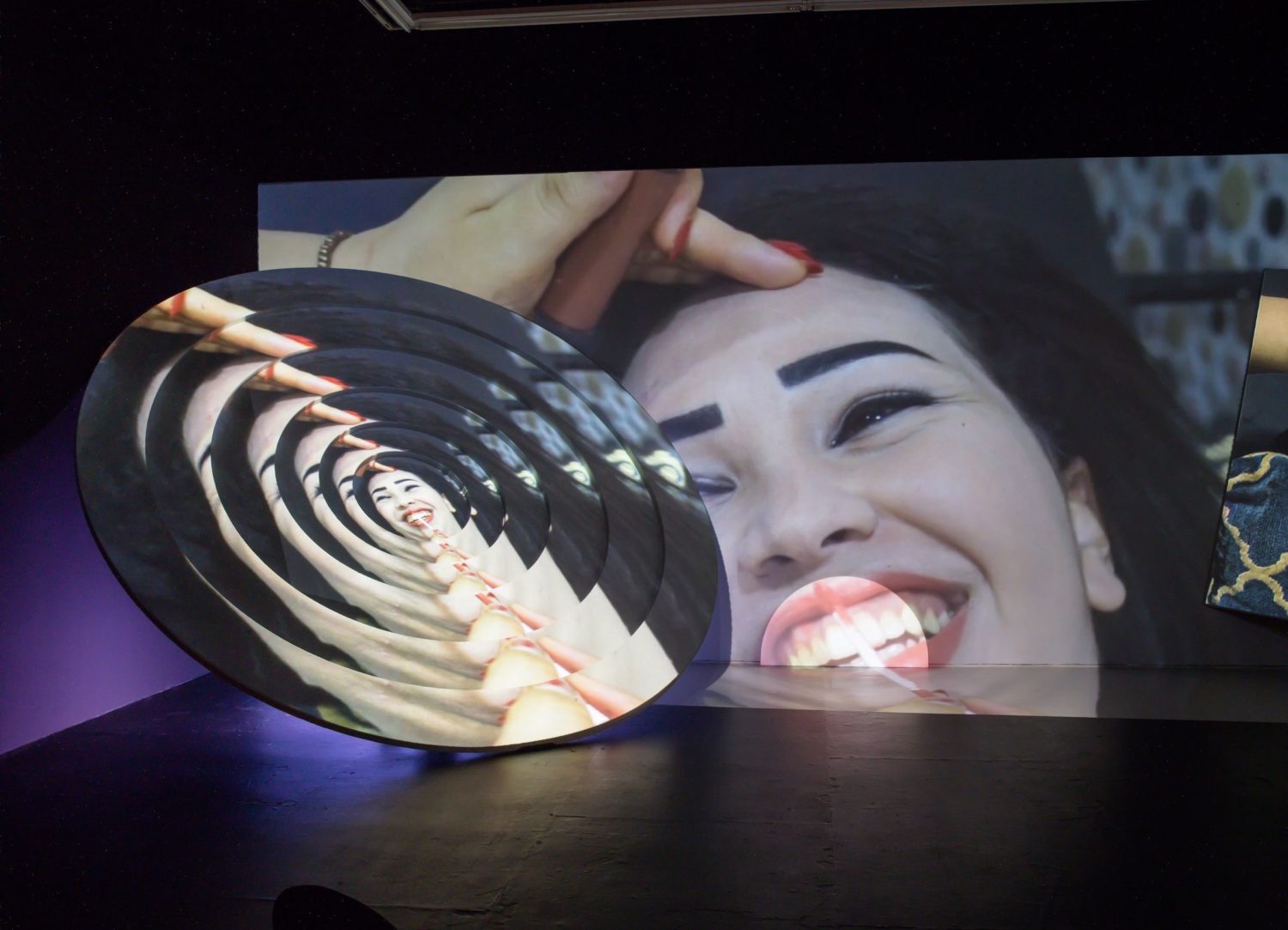

Together with history in a room filled with people with funny names 4, 2017 || Korakrit Arunanondchai

“Will you find beauty in this sea of data?” asks Korakrit Arunanondchai, speaking in his native Thai, in Together with history in a room filled with people with funny names 4. The film interweaves autobiographical elements, allusions to current events in Thailand and the United States, and hypnotic post apocalyptic visions. Opening with footage of Arunanondchai’s grandmother, who has dementia, as she touches various objects in her home whose personal significance she can no longer remember, the work segues into a poetic, dreamlike montage structured around a dialogue between the artist and a personal cosmology. This is the fourth episode in a series that investigates the entanglement of spirituality, technology, nature, and memory.

Siham & Hafida, 2017 || Meriem Bennani

In her Biennial work, MISSION TEENS: French School in Morocco, Meriem Bennani interviews teenagers in Morocco who attend French schools, a relic of colonialism that the artist also experiences as a French-educated Moroccan. As in much of Bennani’s video work, MISSIONS TEENS combines multiple visual languages, drawing on the aesthetic and narrative conventions of documentary, reality television, advertising, social media, and digital animation. Bennani often exhibits her work in multisensory environments rather than on a single monitor or screen, exploring the new patterns of media consumption that have developed around smartphones and other portable devices.

Civil War, 2017 || Josh Kline

Josh Kline explores the conditions of technology, politics, and labor, employing new tools and materials to transform and comment on cultural touchstones. Kline began a science-fiction cycle of works in 2014 to imagine both the possibility and the ruin embedded in our contemporary moment. In earlier projects Kline imagined what might happen if extreme political factionalism, economic inequality, and mass automation continue unabated. Kline directs his focus toward catastrophic climate change and its systemic causes.

Everyone grows relief, 2016 || Olga Balema

Olga Balema uses a wide range of found and fabricated objects in her sculptures and installations, referencing art history, cinema, literature, and personal narratives. Consistent throughout all of her work, however, is her interest in the notion of discomfort. In two of the works shown in the Biennial, Balema suspends unusual materials such as latex and fabric over metal armatures, creating a sense of unease. In Bread of Life, for example, she roughly wraps a length of beige tulle over steel rods, emphasising the tension between these two material elements.

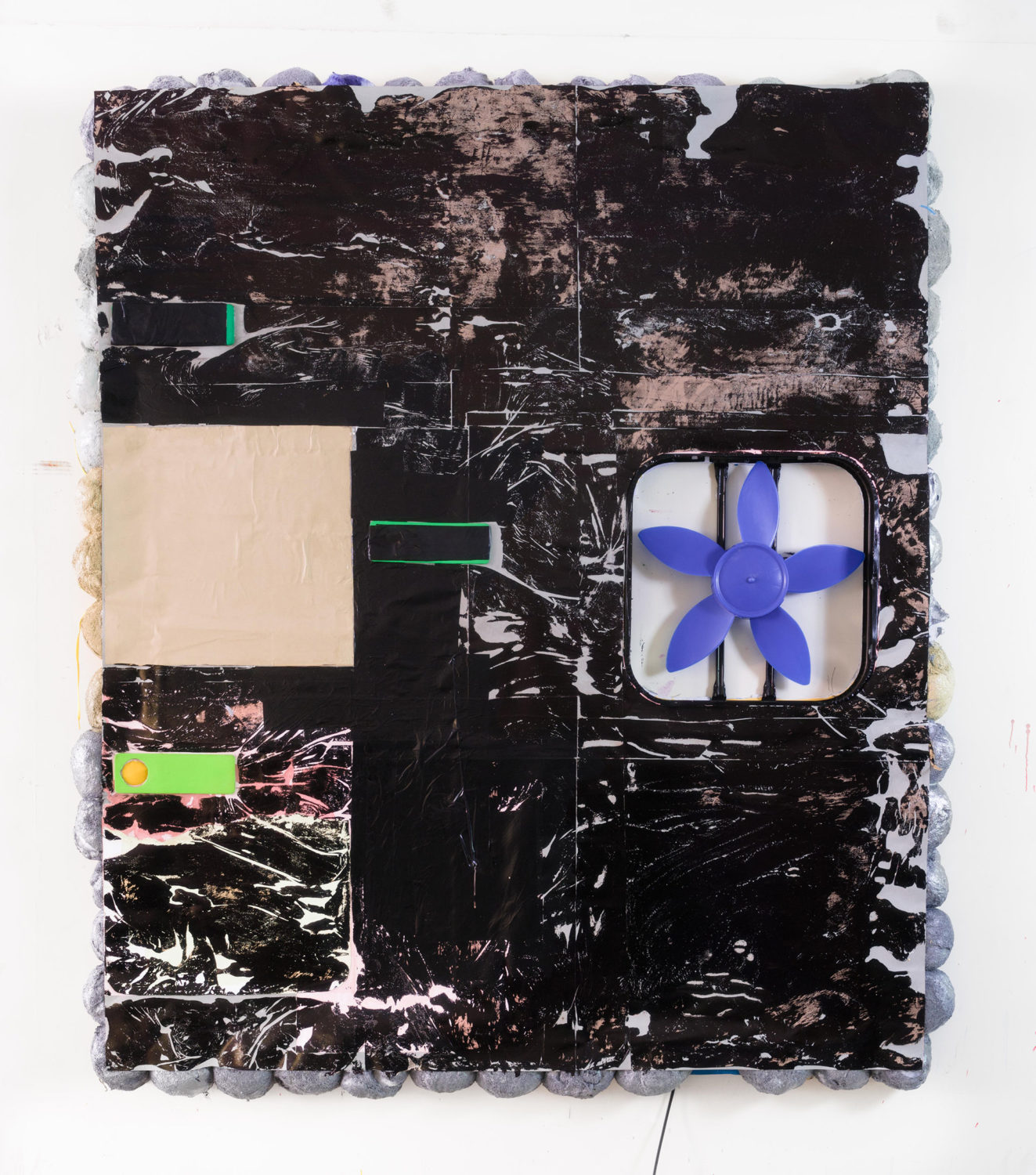

Untitled (Fan Puff), 2016 || Brian Belott

Brian Belott plays with and expands the parameters of painting, collage, and sculpture by encasing various pigments and abject objects that he has accumulated—among them, toothpaste, doorknobs, mustard, and an abacus—into rectangular blocks of ice. Backlit by light boxes inside industrial freezers, these frozen slabs of everyday detritus are temporarily transformed into spectacular multi-coloured ingots suggesting stained glass.

The Nonconformist, 2017-2019 || Lucas Blalock

In his images, Lucas Blalock uses the central tools of photography—the camera as well as Photoshop, which has become ubiquitous in the commercial photography that saturates contemporary life—to explore deceptively simple subjects. When Blalock started using photo editing software, he recalls that the effect of the polished, seamless image seemed “a newly inadequate picture of our world,” prompting him to seek ways to break the conventions of digital manipulation and its pretence of perfection.

Bondage Baggage Prototype 4, 2018 || Maia Ruth Lee

In Bondage Baggage, Lee re-creates packages that she grew up seeing in the Kathmandu Tribhuvan Airport in Nepal: luggage that Nepalese migrant workers packed when they returned home from employment in the Middle East. Tightly bound with rope, tape, tarp, fabrics, and cardboard for added security, Bondage Baggage models a condition of the self, as well as concepts of self-preservation, diaspora, the family, and the economic oppression of developing countries.

Feature image: Korakrit Arunanondchai, No history in a room filled with people with funny names 5, 2018. Image courtesy the artist; boychild; Carlos/Ishikawa, London.