How A Nude Le Corbusier Vandalised Eileen Gray’s Modernist Icon

By Keshav AnandA pioneer of modern design and architecture, Eileen Gray was one of few women to practice professionally in these largely male dominated fields before World War II. Born into an aristocratic household in Ireland in 1878, Gray spent her childhood between her family home, Brownswood House, in Ireland, and the family’s residence in South Kensington, London. In her early twenties she studied at the Slade School of Art, where she formed friendships with artists including Wyndham Lewis, Kathleen Bruce, Jessie Gavin, and Jessica Dismorr. Gray developed at this time an interest in traditional Asian lacquer and studied briefly with artist Charles Dean.

Weary of the London scene, in 1902 Gray relocated to Paris, continuing to pursue her art training. By the end of the decade, she and her fellow Slade peer, Evelyn Wyld, established a workshop to produce carpets and wall hangings. Gray also continued her study of traditional lacquer with Japanese craftsman Seizo Sugawara, with whom she formed a prolific partnership. In 1922, she opened her Paris shop, Galerie Jean Désert, at 217, rue du Faubourg-Saint-Honoré, where she sold home décor items. The Galerie also functioned as an exhibition space for modern art, making Gray, albeit working under a male pseudonym, one of the first female gallerists.

An open bisexual, Gray rejected traditions of marriage, determined to carve her own path. She mixed in the queer circles of the time, being associated with Romaine Brooks, Loie Fuller, Marie-Louise Damien, and Natalie Barney. In 1926, her then partner, the architecture critic Jean Badovici, suggested she find a spot in the South of France for a summer home for the couple. Excited by the prospect, after much searching, Gray decided upon a secluded hillside site, unreachable by car, located within a bushy grove of lemons and banana palms. There, she conceived an idyllic retreat, rendered in bright white and drenched in sunlight, replete with stylish but ultimately pragmatic finishings, dubbing the exquisite holiday home E-1027.

The distinctive property’s exterior comprised a rectangular box impacted into the hillside, bolstered by pillars, and disrupted only by a simple cube with horizontal strips of dark shuttered windows. Paying close attention to the types of furniture that would sit within the building, as well as the way its inhabitants would interact and navigate through the space, the design of E-1027 was immensely influenced by comfort. Custom built cabinets and drawers fitted seamlessly into rooms, with conveniently designed storage for summer apparel, while cosy alcoves provided opportunities for privacy, and thoughtfully positioned windows framed the most striking of views.

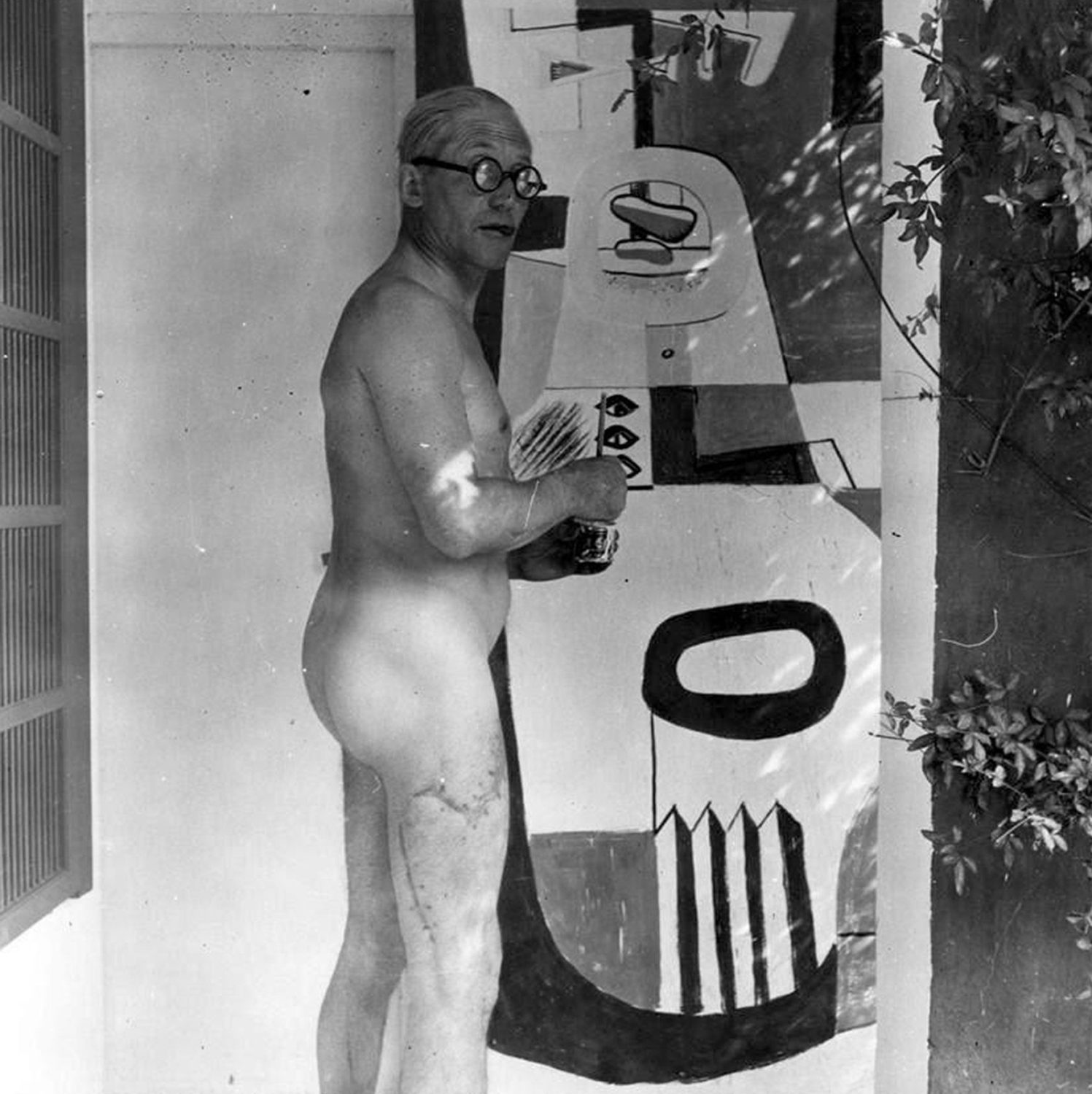

Peppered throughout were an assortment of chairs for every mood and postural requirement, alongside elegant drinks trolleys, reading stands and coffee tables. When E-1027 was finally completed in 1929, Gray was 51 years old. Sadly, the project was ill fated; it never functioned as the romantic getaway nest the couple had intended, and the pair split up within months. The bad luck continued in the years to come when Badovici invited his friend Charles-Édouard Jeanneret to stay at E-1027 with his wife, Yvonne. Jeanneret, who self-styled himself as Le Corbusier, had recently gained international acclaim for his Villa Savoye, and came to the seaside to unwind, sprawling around E-1027, often in the nude, as is well documented.

Gray asserted a home was a living organism, and had irritated Le Corbusier by questioning his thinking that a home was a “machine for living in.” E-1027 left Corbusier perplexed by how someone untrained in architecture, and a woman no less, could execute something so remarkable. This became a point of frustration for him, and he eventually felt the need to act in some way. He decided the white walls needed intervention and he painted eight provocative murals of Picasso-inspired female figures, some suggestively entwined, intended to mock Gray’s bisexuality. Angered, Gray defined these unwanted murals as an act of vandalism. After heated arguing, Badovici ultimately told Le Corbusier he was no longer welcome in the home.

Though Le Corbusier defended his actions later in writing, saying he was simply bringing some colour to the building, Gray was left justifiably offended. Word War II interrupted things, and E-1027 temporarily became a base of the Italian military. In 1956, Badovici, who had owned the property, passed away, and in and odd twist it was Le Corbusier who arranged for it to be sold to an affluent Swiss widow named Marie-Louise Schelbert. Schelbert in turn passed the home onto her doctor, an alleged morphine addict, Peter Kaegi, who was gruesomely murdered there in what a police report described as a sex tryst gone wrong. After that, E-1027 was abandoned and occupied by squatters.

Only relatively recently, the renovation of Gray’s villa occurred, opening to the public after decades of neglect in 2015. Cultural network Cap Moderne, covering the steep hillside between Monaco and the Italian border, accommodates Gray’s villa as well as Le Corbusier’s home, operating as a living museum highlighting the creativity that drove 20th century Modernism. Offering further insight into Gray, curated by Centre Pompidou’s Cloé Pitiot, a new exhibition, Eileen Gray, originally scheduled to run until 12 July 2020 at New York’s Bard Graduate Center Gallery, and discoverable in part online, explores the pioneering designer and architect’s rich practice and varied collaborations. The exhibition is accompanied by a fully illustrated catalogue designed by Irma Boom and distributed by Yale University Press.

Feature image: Le Corbusier’s paintings on E-1027’s walls during renovation, 2009-2017 (via Pinterest)