Studio Olafur Eliasson’s Quarantine Reading List

By Something CuratedDanish-Icelandic artist Olafur Eliasson consistently seeks to make his art relevant to society at large, engaging the public in striking ways both inside and outside the museum. For Eliasson, the potential of art is determined by the viewer’s own participation in and experience of the work. Covering a diverse range of media, from painting, sculpture, and photography, to architectural projects, installations, and ambitious interventions in urban space, his works continually prompt us to think about the nature of perception, addressing pertinent social and environmental issues. While we remain largely housebound, Studio Olafur Eliasson shares with Something Curated a thought provoking edit of reading material to discover.

Timothy Morton, Being Ecological, 2018

Don’t care about ecology? This book is for you. Timothy Morton sets out to show us that whether we know it or not, we already have the capacity and the will to change the way we understand the place of humans in the world, and our very understanding of the term ‘ecology’. A cross-disciplinarian who has collaborated with everyone from Björk to Hans-Ulrich Obrist, Morton is also a member of the object-oriented philosophy movement, a group of forward-looking thinkers who are grappling with modern-day notions of subjectivity and objectivity, while also offering fascinating new understandings of Heidegger and Kant. Calling the volume a book containing ‘no ecological facts’, Morton confronts the ‘information dump’ fatigue of the digital age, and offers an invigorated approach to creating a liveable future.

Doreen Massey, For Space, 2005

In this book, Doreen Massey makes an impassioned argument for revitalising our imagination of space. She takes on some well-established assumptions from philosophy, and some familiar ways of characterising the 21st century world, and shows how they restrain our understanding of both the challenge and the potential of space. The way we think about space matters. It inflects our understandings of the world, our attitudes to others, our politics. It affects, for instance, the way we understand globalisation, the way we approach cities, the way we develop, and practice, a sense of place. If time is the dimension of change then space is the dimension of the social: the contemporaneous co-existence of others. That is its challenge, and one that has been persistently evaded. For Space pursues its argument through philosophical and theoretical engagement, and through telling personal and political reflection.

Francisco J. Varela, Eleanor Rosch & Evan Thompson, The Embodied Mind, 1992

The Embodied Mind provides a unique, sophisticated treatment of the spontaneous and reflective dimension of human experience. The authors argue that only by having a sense of common ground between mind in Science and mind in experience can our understanding of cognition be more complete. Toward that end, they develop a dialogue between cognitive science and Buddhist meditative psychology and situate it in relation to other traditions such as phenomenology and psychoanalysis.

Jane Bennett, Vibrant Matter, 2010

In Vibrant Matter the political theorist Jane Bennett, renowned for her work on nature, ethics, and affect, shifts her focus from the human experience of things to things themselves. Bennett argues that political theory needs to do a better job of recognising the active participation of nonhuman forces in events. Toward that end, she theorises a “vital materiality” that runs through and across bodies, both human and nonhuman. Bennett explores how political analyses of public events might change were we to acknowledge that agency always emerges as the effect of ad hoc configurations of human and nonhuman forces. She suggests that recognising that agency is distributed this way, and is not solely the province of humans, might spur the cultivation of a more responsible, ecologically sound politics: a politics less devoted to blaming and condemning individuals than to discerning the web of forces affecting situations and events.

Created in 1988 by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), the objective of the IPCC is to provide governments at all levels with scientific information that they can use to develop climate policies. The IPCC prepares comprehensive Assessment Reports about knowledge on climate change, its causes, potential impacts and response options. The IPCC also produces Special Reports, which are an assessment on a specific issue and Methodology Reports, which provide practical guidelines for the preparation of greenhouse gas inventories. An open and transparent review by experts and governments around the world is an essential part of the IPCC process, to ensure an objective and complete assessment and to reflect a diverse range of views and expertise.

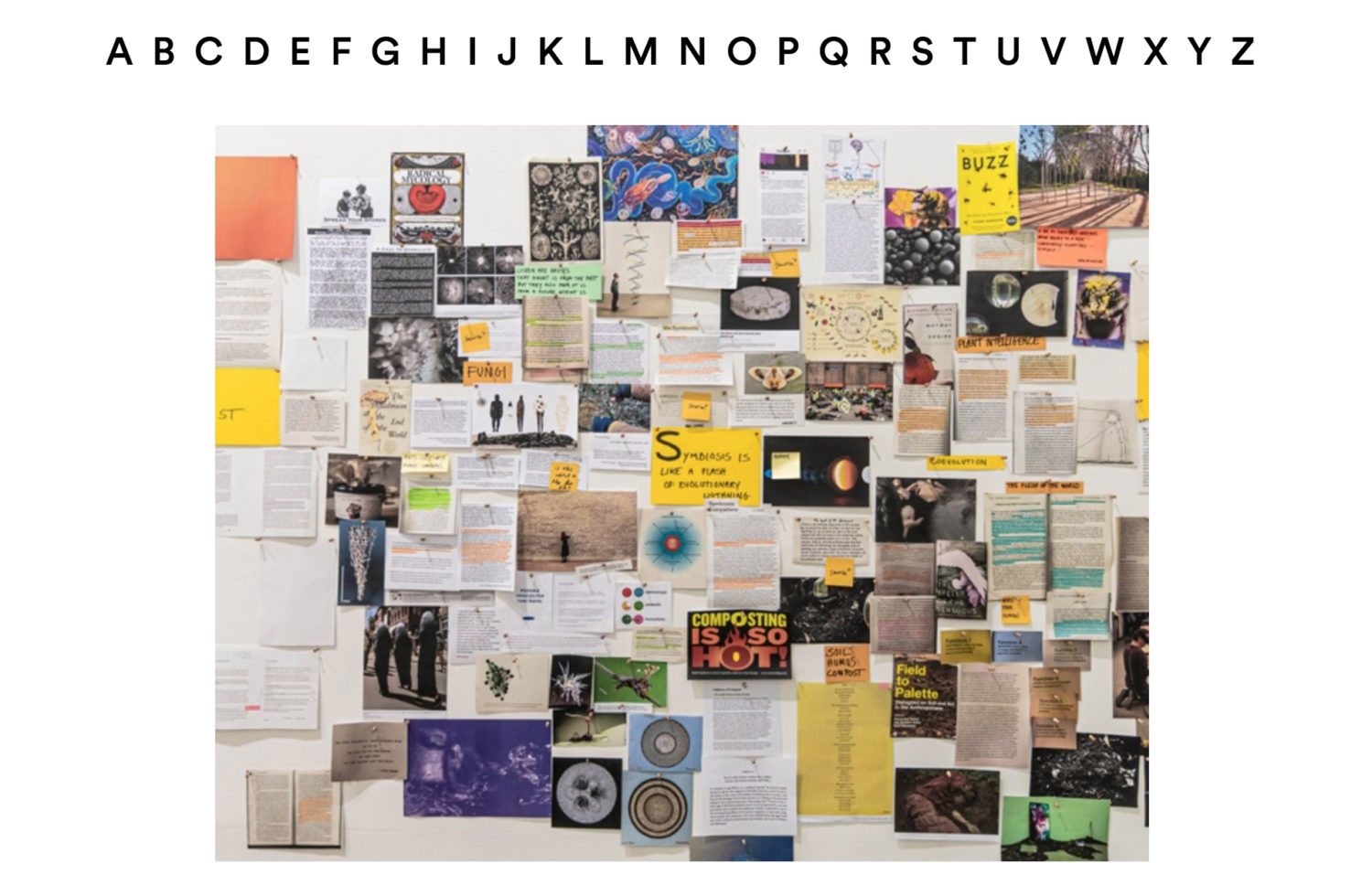

Here you will find the content and credits of the books, essays, articles, artworks, and images that have been included on the pin-walls in Eliasson’s exhibitions Symbiotic seeing, at Kunsthaus Zürich and In real life, at Tate Modern, London. Large panels replicate the pin-boards on the studio walls in Berlin, where Olafur and the team collect content across disciplines that informs and leads to projects such as Little Sun, Ice Watch, and Green light – An artistic workshop.

Feature image: Olafur Eliasson, Riverbed, 2014. Installation view at Louisiana Museum of Modern, Art, Humlebæk, Denmark, 2014. Photo: Anders Sune Berg.