6 Contemporary Artists Using Textiles To Interrogate Histories Of Colonialism

By Something CuratedFrom khadi, a hand-woven natural fibre cloth originating from the Indian subcontinent, adopted by Mahatma Gandhi as part of a key movement to boycott British manufactured cloth, to Dutch wax prints, an omnipresent material found abundantly in Africa with a surprising backstory, textiles are laden with historical context, inherently linked to global geopolitics as well as colonial pasts. Artists have long utilised textiles as a means of expressing ideas, appropriating and subverting the versatile medium in countless ways. Something Curated takes a closer look at six contemporary artists unpacking and interrogating the complex sagas of imperialism imbued in cloth.

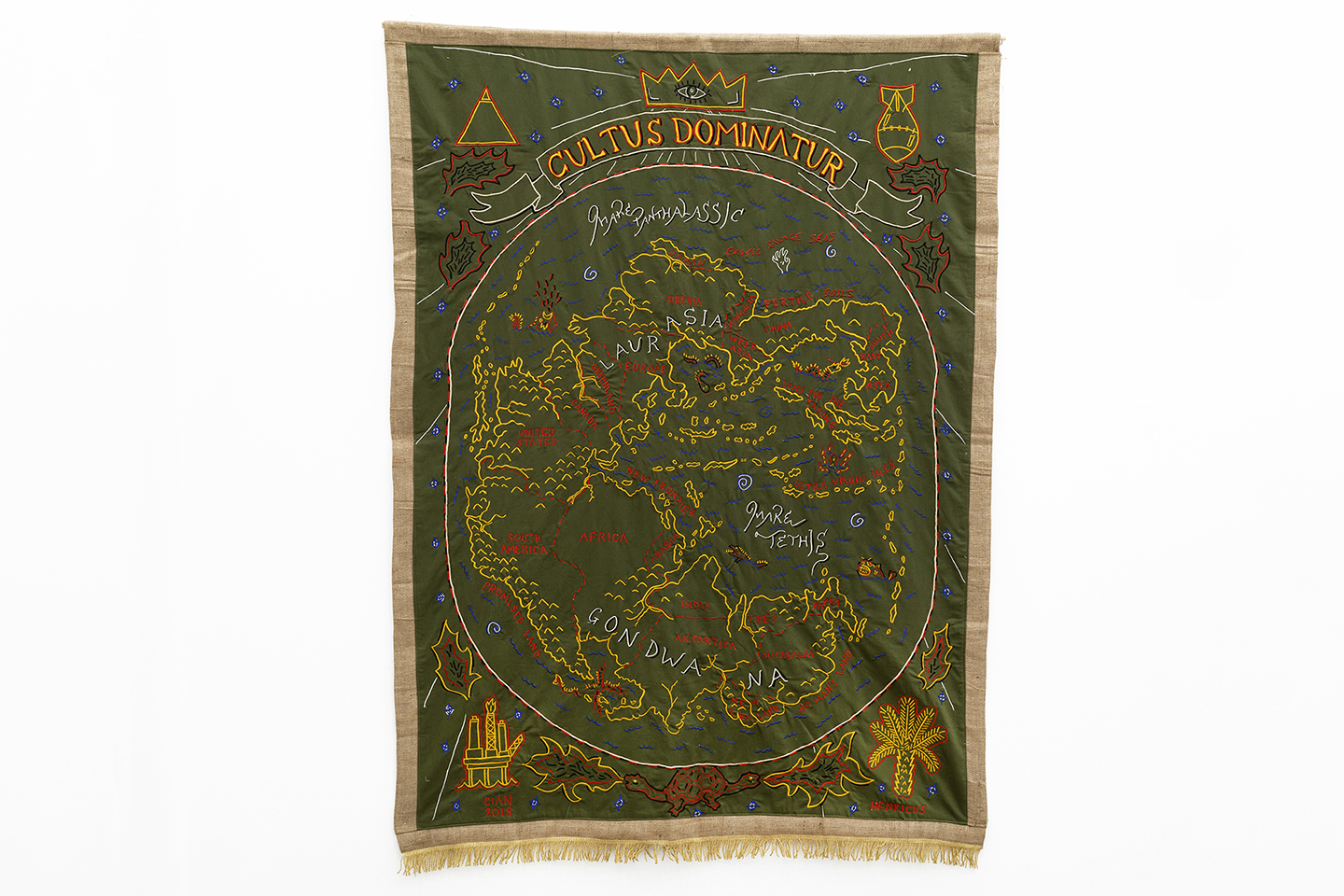

Cian Dayrit

Filipino artist Cian Dayrit’s practice draws from his extensive research into post-colonial legacies, counter-cartography, historical narratives and ancient mythologies. He creates elaborate visual compositions offering a critical examination of the seduction of nativism and nationalism within the moral universe of Filipiniana. The artist previously worked with archival photographs taken by Dean Worchester during his travels to the Philippines between 1890 and 1913; Dayrit’s critical reassessment of these images aims to dismantle the colonial gaze and imperialist view of indigenous culture. The artist uses textiles, talisman appliques and embroidered text to give new meanings to the photographs, in this way subverting their colonial frame and challenging the ways in which past and present have been severed by political necessity.

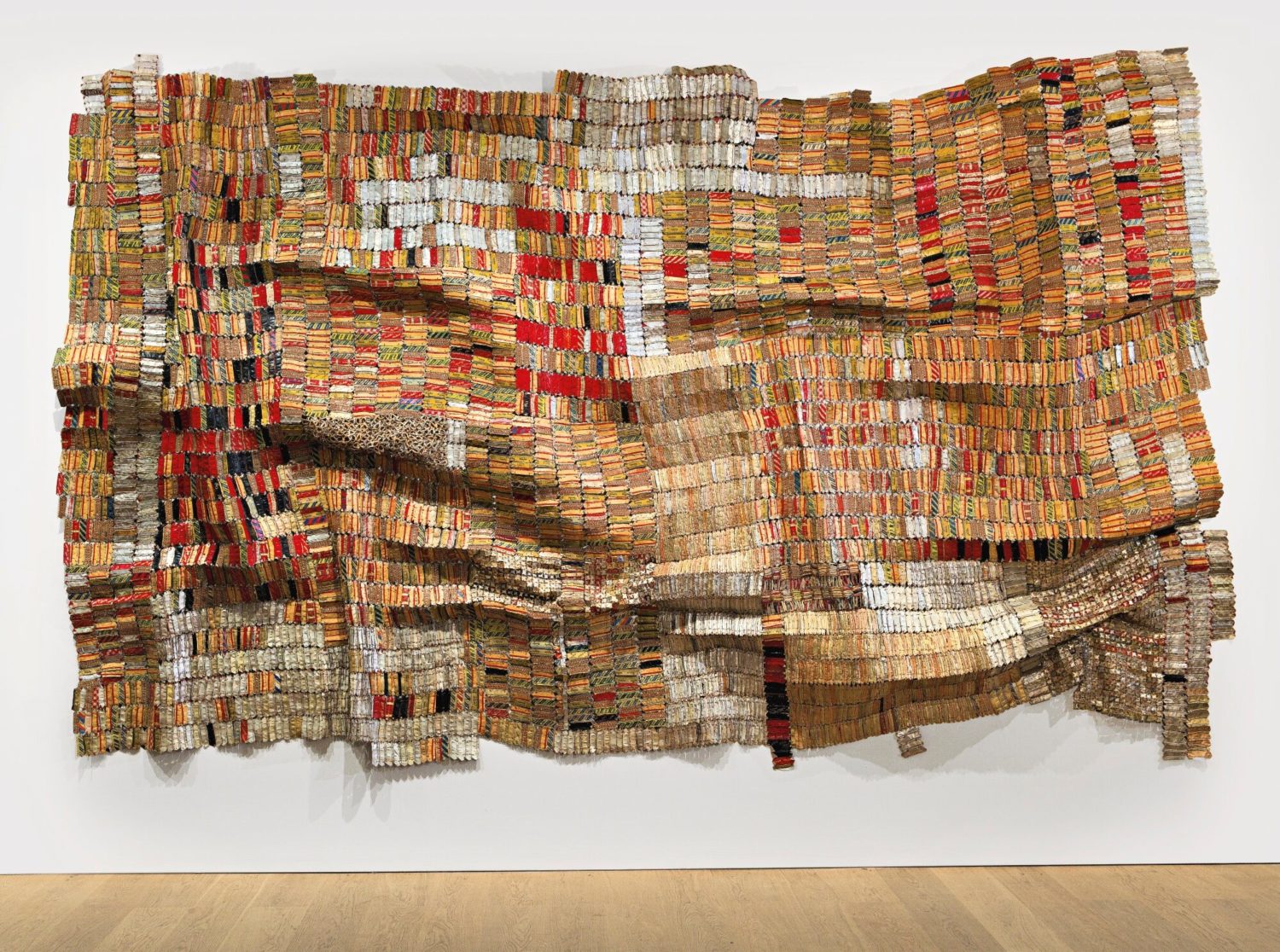

El Anatsui

El Anatsui pursues the themes of memory and loss in his works, especially the damage wrought by the colonial period and post-colonial aftermath. He uses cloth as a metaphor for both the fragility and the dynamism and strength of tradition. In his work, Old Man’s Cloth, 2003, for example, Anatsui’s choice of discarded liquor bottle caps as a medium has as much to do with their formal properties as with their historical associations. The artist explains, “Alcohol was one of the commodities brought with [Europeans] to exchange for goods in Africa. Eventually alcohol became one of the items used in the transatlantic slave trade. They made rum in the West Indies, took it to Liverpool, and then it made its way back to Africa. I thought that the bottle caps had a strong reference to the history of Africa.” The luminescent gold colours also recall the colonial past of Anatsui’s home country; Ghana was previously a British colony called The Gold Coast until its independence in 1957.

Yinka Shonibare

British-Nigerian artist Yinka Shonibare’s work explores cultural identity, colonialism and post-colonialism within the contemporary context of globalisation. A key material in Shonibare’s work since 1994 is the brightly coloured “African” fabric, Dutch wax-printed cotton, which he buys himself from Brixton market in London. “But actually, the fabrics are not really authentically African the way people think,” says Shonibare. “They prove to have a crossbred cultural background quite of their own. And it’s the fallacy of that signification that I like. It’s the way I view culture – it’s an artificial construct.” Shonibare points out that the fabrics were first manufactured in Europe to sell in Indonesian markets and then they were sold in Africa, when they were rejected in Indonesia. The artist examines, in particular, the construction of identity and the tangled interrelationship between Africa and Europe and their respective economic and political histories.

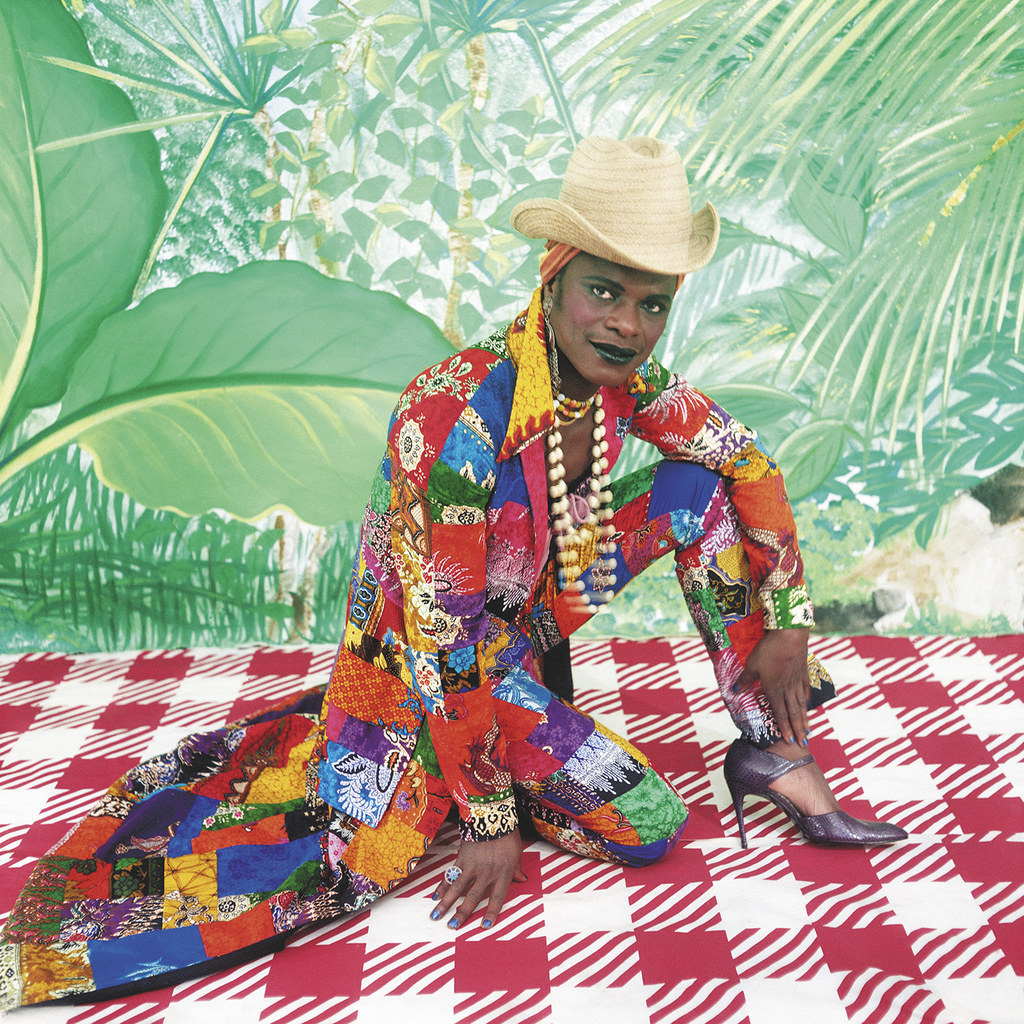

Samuel Fosso

Born in Cameroon to an Igbo family, photographer Samuel Fosso lived in Nigeria as a child, until the Biafran War forced him to flee. He moved to Bangui, Central African Republic, in 1972, when he was 10 years old. Fosso’s early work wasn’t about war and death; it was about the playful style of the streets of Bangui. The artist’s later work is more overtly political. In his self-portraits, textiles play an important symbolic role. In The Chief Who Sold the Africans to the Settlers, 1997, Fosso surrounds himself with colourful fabrics ubiquitous across Africa. Called lapa in Nigeria, panya in the Congo, and kitenge in Kenya, these textiles are from the same family of fabrics Shonibare works with. In The Liberated American Woman of the ’70s, 1998, Fosso refashions the fabrics in rebellious patchwork, reinterpreting them as a symbol of freedom. In The Dream of My Grandfather, 2003, the artist sits atop adire, an indigo-dyed cloth native to West Africa, practiced well before foreigners left their cottons on African markets. The cloth, which can take on any number of patterns, symbolises wealth and fertility.

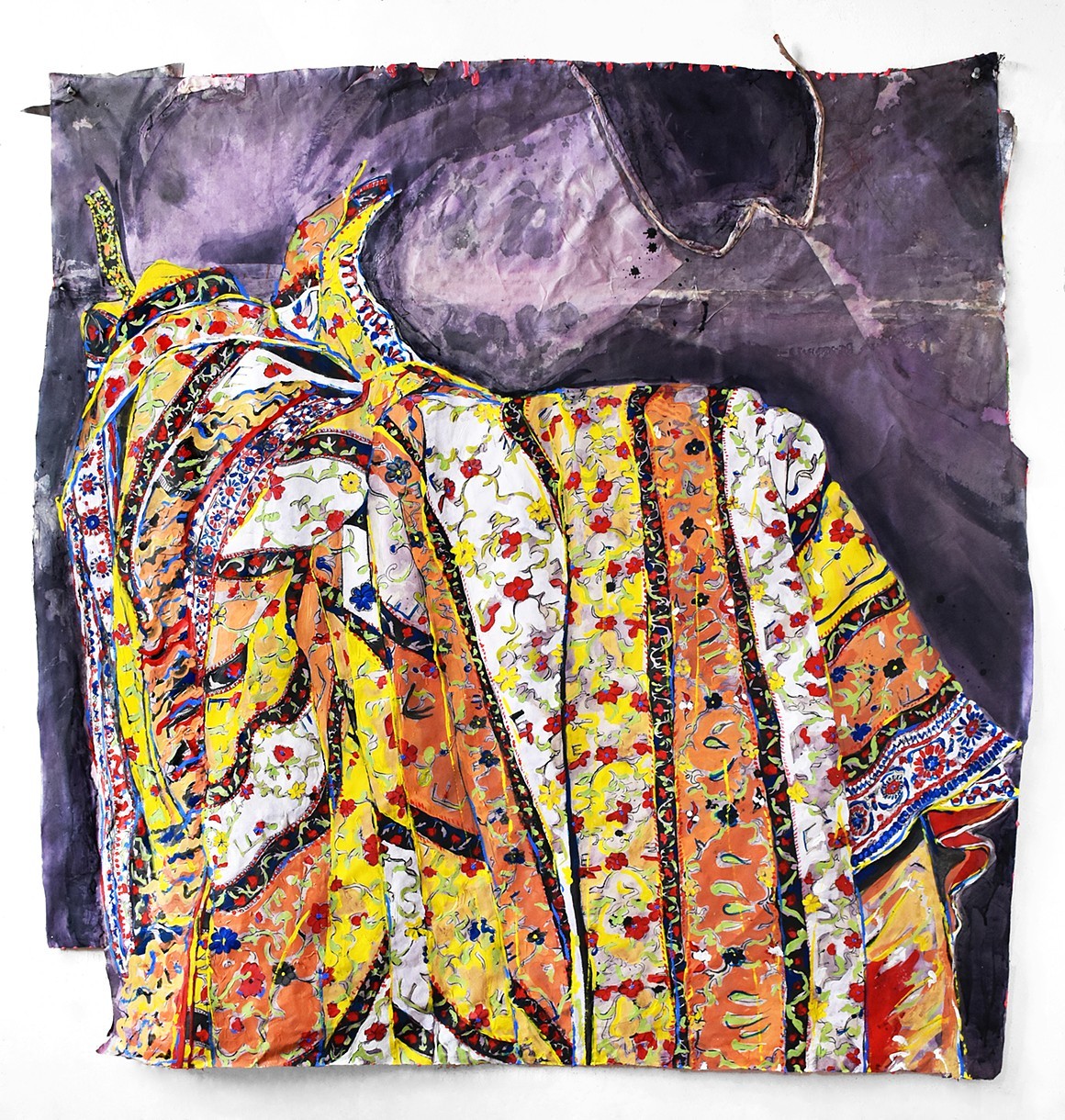

Meena Hasan

New York-based artist Meena Hasan probes the power structures present in her images, questioning given hierarchies and suppositions. The artist presents the Asian American experience by means of subtle manipulation of the everyday. Like all children of immigrants, she has inherited the post-colonial legacies of her family, and her works reveal complex and malleable ideas of self that lead to subject recognition, misrecognition and environments rich with textures and colours that mirror and distort the figures inhabiting them. In her recent works, Hasan investigates two aspects of the decorative: floral textiles and yellow-gold jewellery. The textiles present are tied to legacies of colonial influence and British intervention into South Asian patterning: the Chintz in John Everett Millais’ Vanessa, 1868, the Bengali Kantha hand-stitched quilt in Putting on Bangles and the Liberty London floral print of her mother’s shirt in Nape (Ambereen at home).

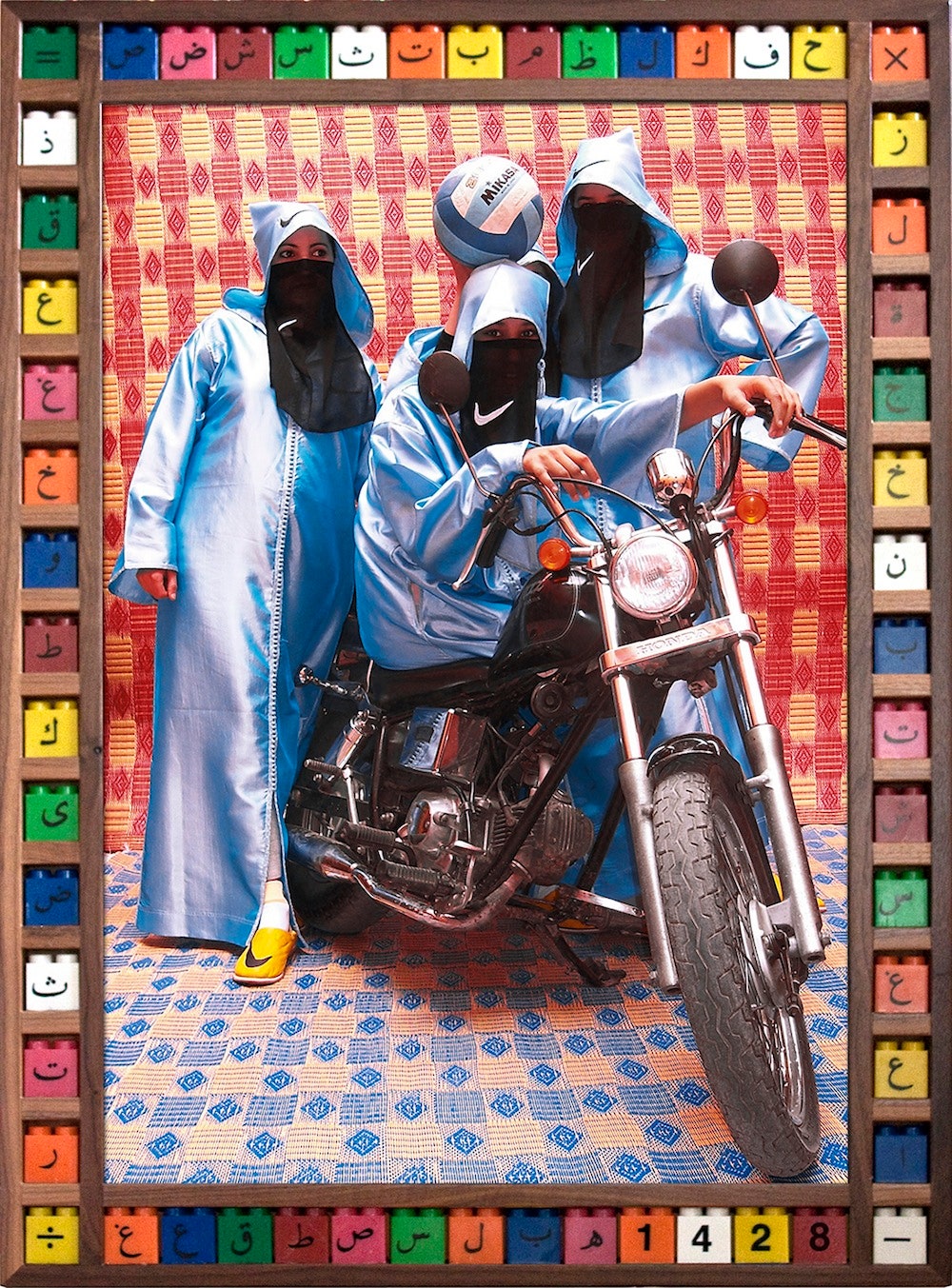

Hassan Hajjaj

Hassan Hajjaj is a contemporary Moroccan artist known for his photography, printed fabrics, and films. Subverting the Orientalist obsession with veiling, in perhaps his best-known series, ‘Kesh Angels, Hajjaj captures the distinctive street culture of young female bikers in Marrakesh. Set within frames of consumables, the artist’s images recontextualise both fine art photography and popular culture. Born in 1961 in Larache, Morocco, Hajajj relocated to London in 1975 at the age of 13. During the 1960s and 70s, following the collapse of French power in Morocco in 1956, Moroccan migration considerably increased owing to the growing need for workers in the newly recovered economies of Europe. Hajjaj’s works explore the mingling of cultures, that of the colonisers and the colonised, within a system of inherent inequality. His works represent the reclamation of both indigenous and non-native cultures under the influence of consumerism.

Feature image: Samuel Fosso, Liberated American Woman/A Self-portrait, 1998 (via Walther Collection)