Nostalgia, Interrupted: How Eastern European Artists Are Reshaping Their Cultural Heritage

By Something CuratedIf you’ve been having nostalgic thoughts or even dreams about places, people and objects from the past since the pandemic started, you’re not alone. When everything feels overwhelming, a trip to a safe and familiar space can be therapeutic, even if that space isn’t necessarily real. But how does one define the boundaries between “real” and “nostalgic” space? As an emigré, the idea of home might exist in a nostalgic micro-terrain made up of fairly elusive features like community, shared traditions, tastes, smells, music, jokes, or associations. To what extent does this space match up with the “real” home? In the case of Eastern Europe, nostalgia itself is an active force shaping the region’s identity and aesthetics. Perhaps “ruin pub” culture can serve as a good allegory – crumbling historic buildings manifest in the hegemonic Western eye as fetishised “ruins”; an image that in turn becomes internalised and sustained as a market. These present a retro paradise for the disposal of thirsty patrons from curious tourists to countless British stag do’s every year.

From their Soviet past through a period of liberal globalisation to a current conservative turn and various degrees of ultranationalist resurgence across Poland, Hungary, Slovenia and Romania, Post-Communist societies are generally still carrying the weight of previous economic and ideological systems. There’s an enduring chasm between cults of tradition and progress affecting cultural production and discourse, which spirals in a vortex of both national politics and an internalised Western gaze. How does one fully embrace progress when appearing less developed pays the bills? How do we untangle the aesthetics of nostalgia from the web of ideological, marketised bias and introduce it into present discourse as a critical (not self-ghettoising) force? This article explores such questions through the practices of four Eastern European artists. Working in both diasporic and regional contexts, they integrate artefacts, symbols and narratives from their heritage with other contemporary perspectives to give shape to the complexities of nostalgia and their experience.

London-based Polish artist Rafał Zajko borrows motifs from pagan parables, agriculture and Soviet rectilinear architecture for his works. These nostalgic tropes are blown into orbit, inhabiting ambiguous retrofuturistic landscapes that oscillate between dystopia and utopia. An example is Zajko’s human-sized Amber Chamber (2020), a mix between brutalist monument, ancient sarcophagus and sterile cryogenic freezing chamber. This bright totemic structure embodies the harvest as both an economic and spiritual event with a wheat icon carved into its chest. The transparent pod contains the cast of the artist’s own head strapped into a mask with long wheat pieces as the reincarnation of the mischievous straw figure Chochoł, who protects rose bushes from winter frost in the 1901 novel by Polish writer Stanisław Wyspiański. This rebirth chamber portrays life, myth and heritage itself within a synthetic metamorphosis.

While grounded in the realm of speculation, Zajko’s sculptures also incubate material histories of labour and industry – wheat, steel, drill bits, cement, and wood. His recent exhibitions Filter (2020) at Goldsmiths College and Resuscitation (2020) at Castor Projects present his ongoing research around wheat as a complex symbolic and somatic framework within rural working-class ecosystems and mythologies. The artist himself grew up in the Polish Region of Podlachia, where daily rituals interlink with systems of agricultural production. In this body of work, the nostalgic and real homes intersect through global systems of production and myth that impact both macro-economic infrastructure and personal consciousness.

Much like in Zajko’s work, the sphere of labour and industry is deeply embedded in Czech artist Anna Hulačová’s nostalgic iconography. Growing up in a Czech village with a family of small farmers and carpenters, she is passionate about the impact of 1950s agricultural collectivisation policies on rural microcosms. Her ongoing series focuses specifically on insect and bee populations. The cement relief Cosmonauts (2018) shows two beekeepers throwing their hands triumphantly in the air like astronauts on a Soviet poster, contrasting nostalgic Space Age optimism with the dystopian ecological outlook of the present. This piece appeared alongside other biomorphic cement sculptures inlaid with delicate pencil drawings on aluminium and paper panels in her exhibition Graceful Ride (2018) at Kunstraum London.

Hulačová’s Social-realist figures are crossed with animals, plants, machines and characters from Greek to Slavic mythology, their facial features fractured into symbols and geometric shapes. Unfolding through robust outer shells of cement or wood, their insides reveal layers of silicone, honeycomb and other tactile materials. A self-admitted “retro-fetishist”, Hulačová fuses the aesthetic of Soviet brutalist architecture with layers of fiction and intricate craft to manifest complex ecological networks. Her and Zajko’s work steer nostalgia into the territory of the future and into utopian/dystopian speculation. Both are interested in composite bodies within which elements of the real and the nostalgic or imaginary clash and give birth to new, non-hierarchical iconographies.

Hungarian multidisciplinary artist Dominika Trapp gravitates away from speculative futures to focus on the critical axis of past and present within Hungarian folk culture. Similar to Hulačová, who creates work collaboratively with other craftsmen in her community, Trapp worked with a musical instrument manufacturer, traditional dancer and an architecture workshop among others on artworks for her exhibition “Don’t lay him on me…” (2020) at Trafó in Budapest. For this project, she deconstructs the nostalgic realm through a manifold inquiry into the somatic conditioning of the female body by hegemonic external forces. This is represented through a range of mediums and research informed by folk culture including vivid figuration, conceptual sculpture, recorded performance and archival documentation.

The Body of the Peasant woman (2020) is a central sound installation based on the real, tragic story recounted from the deathbed of an elderly woman who had given birth to 15 children from an abusive husband (which also gave the exhibition its title). This was adapted from “Asszonyok könyve” (“The Book of Women”) by ethnographer Olga Nagy – an anthology of interviews with peasant women in Hungary from the 1970s and 80s. The two smaller wooden structures are composed of different traditional chairs, the birthing chair at the bottom built in with a dead toddler’s casket in the middle and the milking chair at the top. Towered over by the domineering paternal seat, the unit of the three symbolic structures represents characters and events from the woman’s story while also tying into a broader history of gendered hierarchies and somatic conditioning within and beyond the traditional family unit. Trapp’s mother and two grandmothers read out personal interviews from “The Book of Women” in the haunting sound piece Asszonysorsok (Women’s Fates) as the living echo of oral and written continuity. This artwork ultimately grounds the nostalgic realm within real and collective space, practicing collaborative gestures of bearing witness to non-hegemonic narratives often overlooked or made invisible by force.

Much of the current political, erotic and economic reality of the female body is subject to such engrained biases in Hungary but also elsewhere in Eastern Europe, as seen with recent abortion laws in Poland. Violent structures of the “real” home as they are imposed onto personal consciousness and body become most clear in these cases.

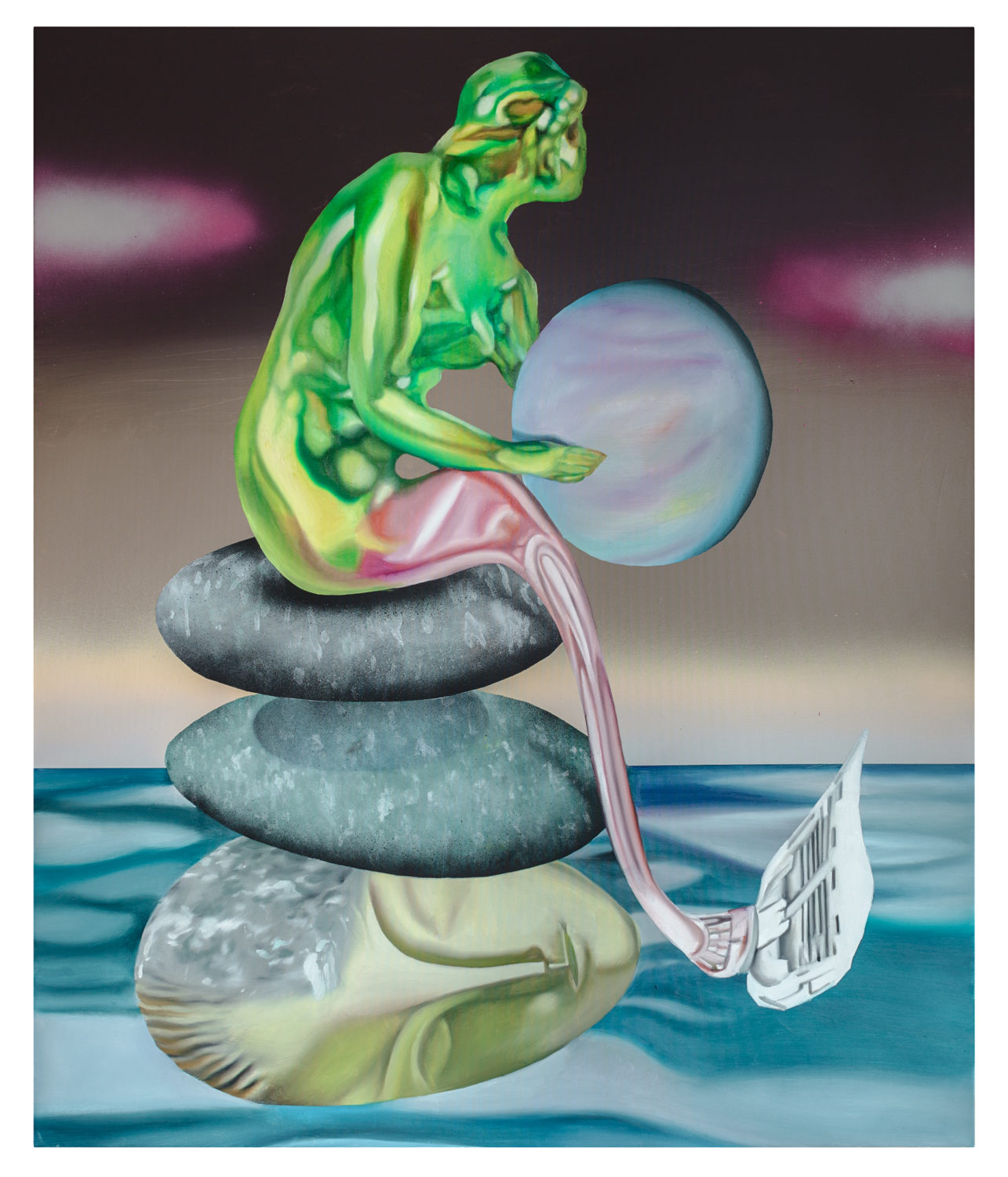

Hungarian-Romanian artist Botond Keresztesi’s paintings strike a more playful tone with nostalgia. His use of coded abbreviations with cheeky double-entendres in his titles are telling of the work’s ironic undertone, such as the recent P.C.P (Professional Camouflage Painters) at WTT Foundation in Kiev and D.D.R (Digital Dreams Recordings) at Future Gallery in Berlin. His future-nostalgic still lives assemble fragments of mainstream digital culture, classical art history and the monuments, landscapes and visual culture of his childhood in a Post-Socialist miner town, Tatabánya in Hungary. Nothing here remains sacred; lava lamps and details from Hieronymus Bosch and Caravaggio works share heads and limbs with Hungarian Zsolnay porcelain figures, mythical animals and surveillance cameras. These synthesised bodies present a kind of trans-evolutionary profile of human obsession. The screen-like surfaces of the paintings are like flattened digital black holes, reflecting the postmodern realm of aesthetics that is constantly accelerated by cyber culture. Keresztesi paints the nostalgic world as one that’s constantly recycled, whether through art, technology or libido. His world confronts the viewer with the relativity of cultural heritage and ideals, including his personal nostalgic home.

Viewed through such intersectional practices, nostalgic timelines reveal themselves to be interwoven with the economic and political biases and violence of real geopolitical space. Once this continuity is embraced, the nostalgic realm offers ways of challenging monolithic hegemony through various interventions or moments of collapse; whether through blending different iconographies within canvases, speculative sculptural forms, or by condensing timelines and foregrounding marginal histories through collective ritual. Progressive nostalgic vocabularies can be rooted in personal history while also given room to hybridise as reflexive tools for present and future realities. Though the artistic realm offers comparatively broad generosity for such expressions, nostalgia and identity are still marketing tools. Much like ruin pubs, peripheral identities tend to become fetishised and commodified, thus artists from marginalised backgrounds will be incentivised to focus on their peripheral identities in order to survive within the dominant system. This factor only adds to the complicated relationship between real and nostalgic home, identity and progress.

Words by Sonja Teszler.

Feature image: Rafal Zajko, Amber Chamber, 2020. Installation view at Castor Projects, London. Courtesy the artist and Castor Projects, London.