Interview: Artist Cydne Jasmin Coleby On Bahamian Textiles & The Women In Her Life

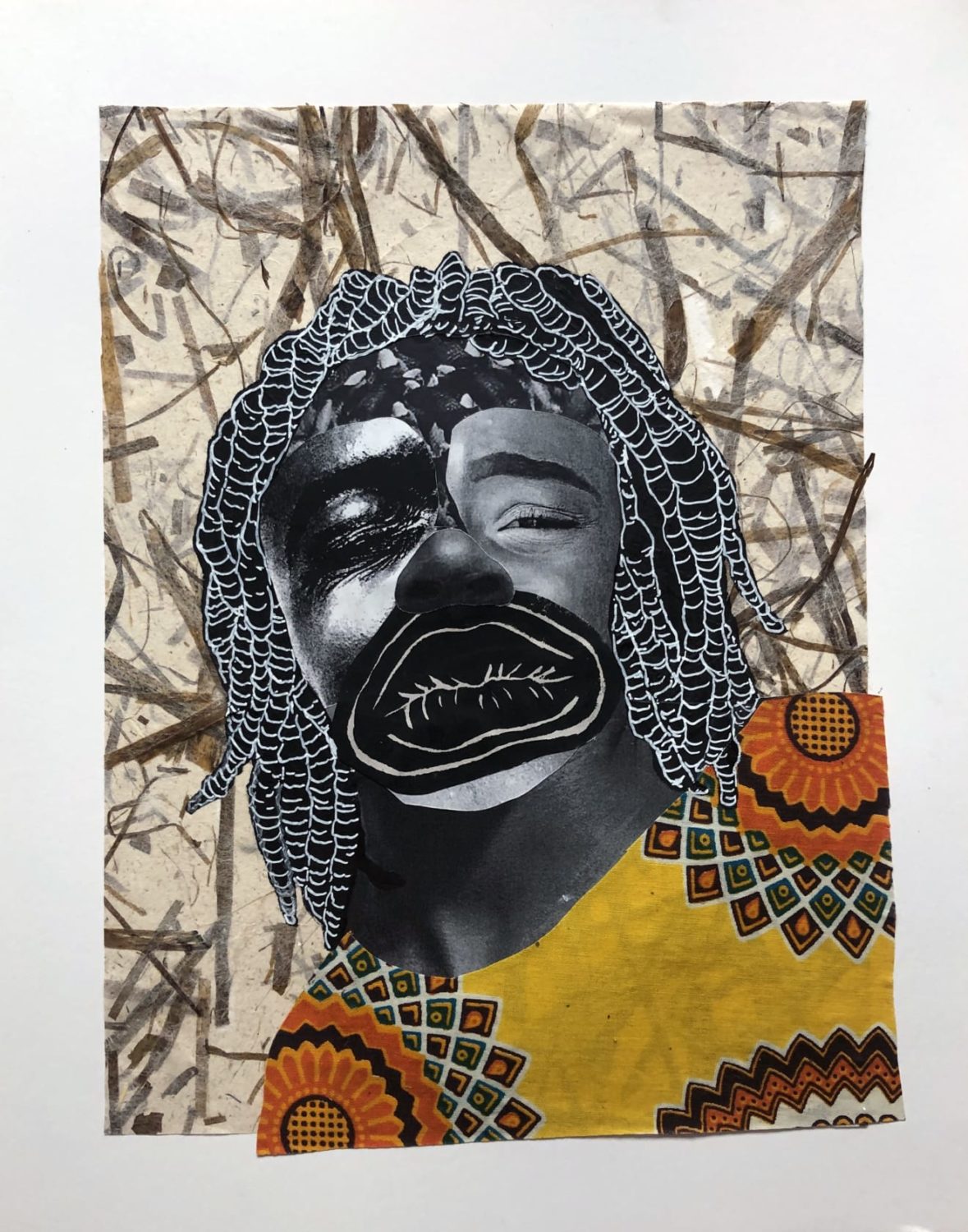

By Something CuratedNassau-based Bahamian artist Cydne Jasmin Coleby considers the matriarchs of the family in her latest body of work. The digital and mixed media collage artist attended The University of The Bahamas, and following a career in graphic design returned to her art practice, going onto exhibit extensively in her native country as well as more recently in Europe. Presented by Unit London and running until 23 April 2021, Queen Mudda is a celebration of Black women and girls. With nods to Rococo alongside the hyper-embellishment of the Caribbean and African diaspora, Coleby’s dynamic works oscillate between the ruffles and frills of the Baroque period and the vibrating patterns of African wax print fabric, Junkanoo, and Carnival. There is a severe exploitation of unseen labour in Black women the world over, and in an age where being is appearing, Coleby offers the matriarchs of her family line the opportunity to appear as elevated as the care they give. To learn more about the artist’s practice and her current exhibition, Something Curated spoke with Coleby.

Something Curated: Can you give us some insight into your background; when did you first become interested in artmaking?

Cydne Jasmin Coleby: My earliest memory of being introduced to fine art was when I walked into the family home of prominent Bahamian artists Stan and the late Jackson Burnside. Their sister, Julia, is good friends with my mother, and when we went to visit her I walked into a house with walls covered in salon-hung paintings. I had never seen anything like it and was just in awe. Julia explained to me that Stan and Jackson were artists, and that was when I knew I wanted to be an artist as well. From then on my parents supported my interest to pursue an art career at every stage of my life.

I enrolled in the College (now University) of The Bahamas’ art programme, but unfortunately I wasn’t able to finish my degree. Despite that, I knew I didn’t want to settle into a non-creative field. So I taught myself how to use Adobe Creative Suite, and worked as a corporate and freelance graphic designer for about eight years. In 2018 I decided to make art again, utilising all I’d learnt and experimented with in college as well as during my time as a graphic designer. And I’d say things have been going well ever since.

SC: Can you tell us about the selection of works included in your upcoming exhibition Queen Mudda at Unit London?

CJC: The works in Queen Mudda are all portraits of women in my family. I wanted to have a show that honoured these women, highlighting them in a space in which they normally wouldn’t see themselves. Inspired by real life photographs, I reimagine the images in a way that retells their stories in vibrant celebration of these women.

SC: How do you think about storytelling through your fascinating works?

CJC: In these works I find the storytelling is a bit more nuanced than in other pieces I’ve made. In traditional portraiture there is a focus on capturing the essence of the people being depicted, and I think that carries over in Queen Mudda. My practice generally speaks on trauma, but with these works I didn’t want that narrative to be at the forefront. I admire the strength and endurance of these women, and wanted to acknowledge them beyond their experiences. Then I take things a step further by empathising myself with these women, incorporating photo collages of elements of my face as a way of highlighting my relationships with them.

SC: Could you expand on your use of materials from African wax print fabrics, to newspaper clippings and plant fibres?

CJC: I’ve always been fascinated by the use of various textures and materials in art. And all of the materials I use in my work, excluding the paint, have some connection physically and/or visually to The Bahamas. The batik wax fabric in my work is actually Bahamian. It’s called “Androsia” and it’s produced on the island of Andros – an island in which I have family roots. The Androsia factory was started by Rose Birch in the 1960’s as an easy, fun, and affordable, in terms of production, way to celebrate the island and provide employment to Bahamian women. Outside of this connection to womanhood, the fabric is also seen as the unofficial fabric of The Bahamas.

You’ll also see in some of the works I’ve mixed Bahamian sand with paint to create texture. There have been a lot of interesting conversations/debates regarding the beaches here – questions about ownership and access, especially during the height of the Covid-19 pandemic when restrictions to beaches were in place. Nonetheless the beach is understood as a birth right and all Bahamians have a right to utilise them. So outside of texture and any conversations as to what that roughness might be interpreted as, the use of sand in my work acts as a marker of a sense of place – a right to my/our homeland.

The crepe paper elements in my pieces are a nod to Junkanoo. Junkanoo is a cultural festival with West African roots that has been used through Bahamian history as an act of rebellion, protest and celebration. And finally the papers that I used, though not made in the Bahamas, are made from trees and plants you’d find here, such as mango and banana.

SC: How has the pandemic affected your way of operating?

CJC: Ironically the pandemic might’ve been the best thing for my art career. It allowed me the time to really focus in the studio unlike I’d been able to before. The only downside I’d say were the lockdowns and curfews. They affected my hours of operation a bit, but outside of that I have no complaints.

Feature image: Cydne Jasmin Coleby, Ushered In, 2021 and Thea in The Garden, 2021