Interview: HQI The Rotunda Founder Muz Azar On White City’s New Experimental Arts Space

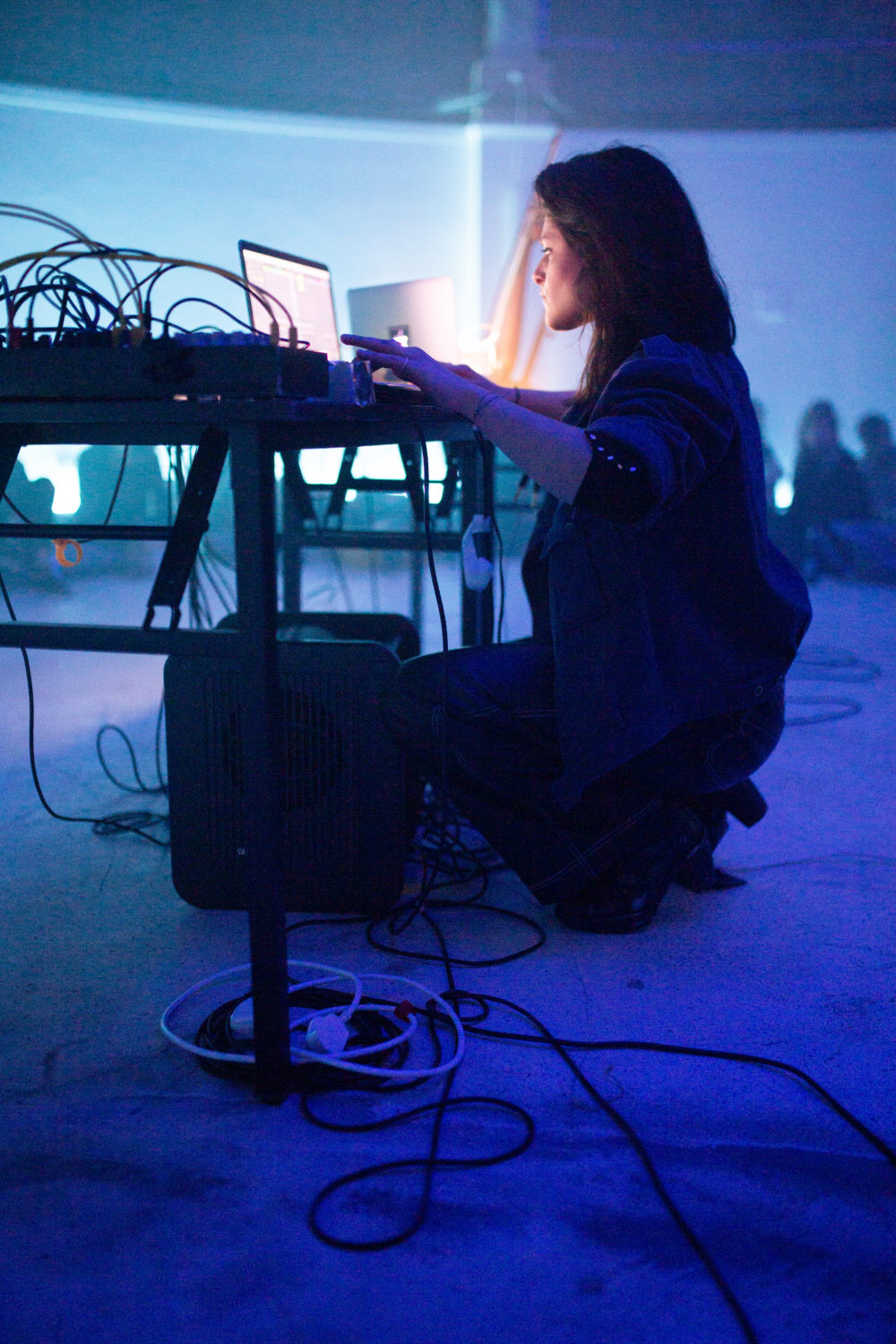

By Something CuratedThe brainchild of Muz Azar, HQI is an artist run non-profit which works with owners of vacant buildings to provide long-term arts facilities to visual and recording artists. The initiative’s first space, HQI The Rotunda, is inside a former BBC social club in White City, London. The project was born from a desire to establish an independent and nurturing space in the city in which to make work that is both collaborative and spontaneous. The site offers 24/7 access to its artist residents with 2 music and video editing studios, a communal visual arts studio, a workshop room and a 1500sq foot exhibition space and music venue. HQI will soon be open for new residency applications, with more information on the process available via their Instagram. All new artists are offered at least 3 months of free space with options to extend or contribute via a fee based on affordability. To learn more about the exciting new initiative, Something Curated speaks with HQI founder Muz Azar.

Something Curated: Can you give us some insight into your background; what interested you in founding HQI?

Muz Azar: London can be a very exciting but also intimidatingly difficult place to live and work when you haven’t quite found your path. When combined with the difficulties every artist will face as they refine their skills, I felt there would be many talented artists for whom the leap towards making their practice a sustainable prospect would be too great. The inevitable outcome seemed to be a potential decline in the diversity and quality of creative output to come out of our city. My own experiences developing as an artist were no different. Despite having the luxury of access to all the tools and resources I needed to make music, increasing isolation from peers and a lack of awareness about establishing healthy live work practices led to burnout and productivity grinding to a halt within a few short years of starting out. I reflected back to times when I was happier and more engaged as an artist, and all signs pointed towards a slow and gradual loss of my creative community. So I began to hatch thoughts of starting an experiment to rekindle a sense of camaraderie akin to what I experienced in earlier years as a giddy and excited artist fresh to London. A series of serendipitous events and meetings with people who felt the same ensued and HQI was born.

SC: What do you hope to achieve with the space?

MA: There are multiple positive outcomes we are looking to achieve with HQI. The first is related to the 25 upcoming artists per year for whom we have the facilities to provide R&D studio residencies. Our hope is that providing a space without a commercial burden, which is both well resourced for work and encouraging of community engagement, will dramatically accelerate the development of each artist’s individual practice. Second, our work would not be possible without the support of forward thinking landlords. Community can somewhat exist online, but it’s really not the same as having an actual space where people can assemble, and so maintaining an empathetic dialogue to the needs of our landlords is key to our sustainable future. We want to ensure our landlords don’t simply feel like they are offering us charity but that they are beneficiaries from a shared mission to support artists in the city, which undoubtedly has both cultural and commercial benefits for local communities, industry and beyond. With this in mind, we have had the good fortune of working with developer Stanhope PLC in establishing HQI. They have entrusted one of their buildings in the old BBC headquarters to us with minimal fuss and I would like to give special mention to Mike Horton and Claire Dawe at Stanhope for championing our cause.

SC: Could you tell us more about the artists you are facilitating, and what the thinking is behind the selection of creatives you’re supporting?

MA: Originally HQI was intended to support musicians as that was the industry I knew best and wherein I had felt support was most lacking. However, based on the physical layouts of our space, it quickly made sense to also open out to visual artists and break away from any precise delineation in our residency intakes. We’ve seen so many unintended positive side effects of combining multiple different disciplines under one roof, that we would certainly go forward in this way again should we start again or open up a new space. A non-silo’d approach to a residency programme also reflects the multidisciplinary nature of a new generation of artists who can learn anything and everything via YouTube, and may not specialise until much later than previous generations.

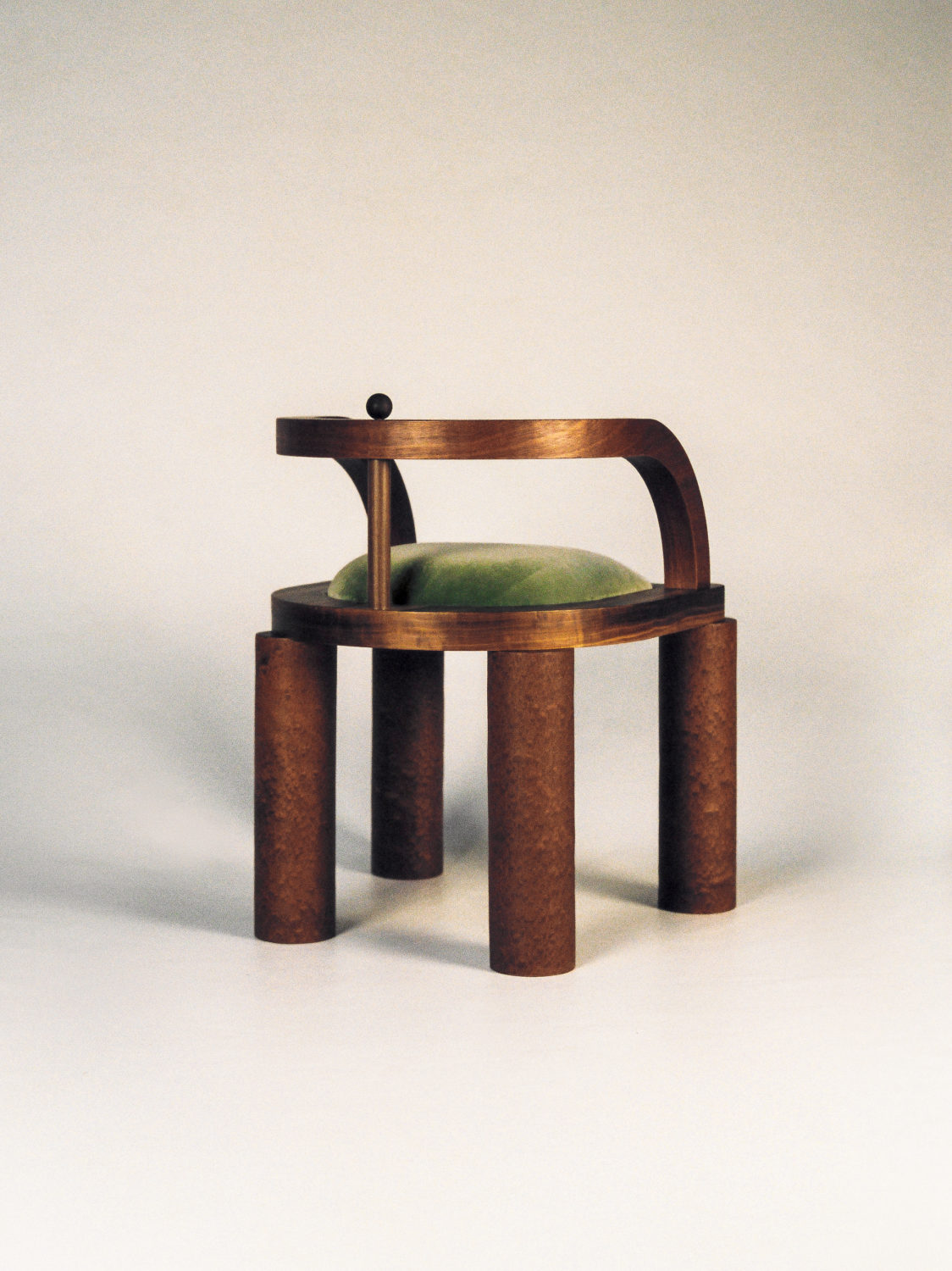

Secondly, each discipline has its own unique set of learned truths and rules which will have beneficial applications to seemingly unrelated disciplines. For example, recent conversations I’ve had with current HQI resident and furniture designer Lewis Kemmenoe has taught me more about minimalist aesthetics than in years of exploring the same old channels in music production. Following on from this, visual arts has a 100 year head start on music in regards to conceptual thinking, and from personal experience is an area in which most producers/musicians are less aware. The practical benefits in developing one’s conceptual frameworks are considerable in their capability to lead someone to yield more original ideas from their work, and potentially more fruitful than reliance on sheer technical prowess alone.

SC: Can you expand on some of the challenges you’ve experienced and have overcome or are still working to?

MA: Building a genuine community is always going to be a challenge but perhaps even more so for artists whose hermetic tendencies may render them particularly ill-equipped to take on the task of building or engaging with a community. We have found one solution is to build a loose framework, an unspoken but casually agreed upon code of conduct which ensures everyone’s trust in the community. The challenge here being to not overdo things so that we avoid our space becoming too formalised and rigid. It is also always difficult to know how to introduce new people to an environment, but this has been made easier by sticking to one rule, which is that no matter how prodigious an artist or their background, they must fundamentally be comfortable and happy to work amongst other people. “Being nice” can be often side-lined as non-essential by artists competing for resources and public attention, but it’s practical applications to inspire creativity should not be overlooked. It is our opinion that happy and safe places are more likely to induce productivity than environments which may seem fashionable on the surface but in-which pervasive self-obsession might actually leave their members insecure, miserable and uninspired in the longer term.

SC:What do you want to learn more about?

MA: I have a hunch that there are many people who aren’t artists and may have no connection to the arts, but who would want to participate in supporting upcoming artists if there were frictionless ways of doing so. Within every institution, company, there will be key decision makers who may be quietly passionate about collecting vinyl, photography, furniture and so on. Unbeknown to them, they may actually be in positions to help support a new crop of artists with access to facilities, sponsorships, mentoring and so on. I would like to learn more about how to engage with such individuals and include them in conversations about building cultural support networks for developing artists in our shared city.

On a personal level, I am also really interested in how people develop high levels of creative thinking and whether it is something that can be distilled, honed and passed on. Historical consensus has been that creative ability is something an individual will either have or won’t as a birthright. I am less sure of this conclusion, find few parallels with other high skill orientated disciplines and often think of children who display near universal creative tendencies no matter their later direction in adult life. My hope is that new findings in brain and behavioural science will shed more light on this most cryptic and misunderstood facet of human thinking, so that people are less likely to give up on their artistic ambitions before the full potential of their creative aptitude and originality of voice have been revealed.

Feature image: Ivor Alice / Courtesy HQI