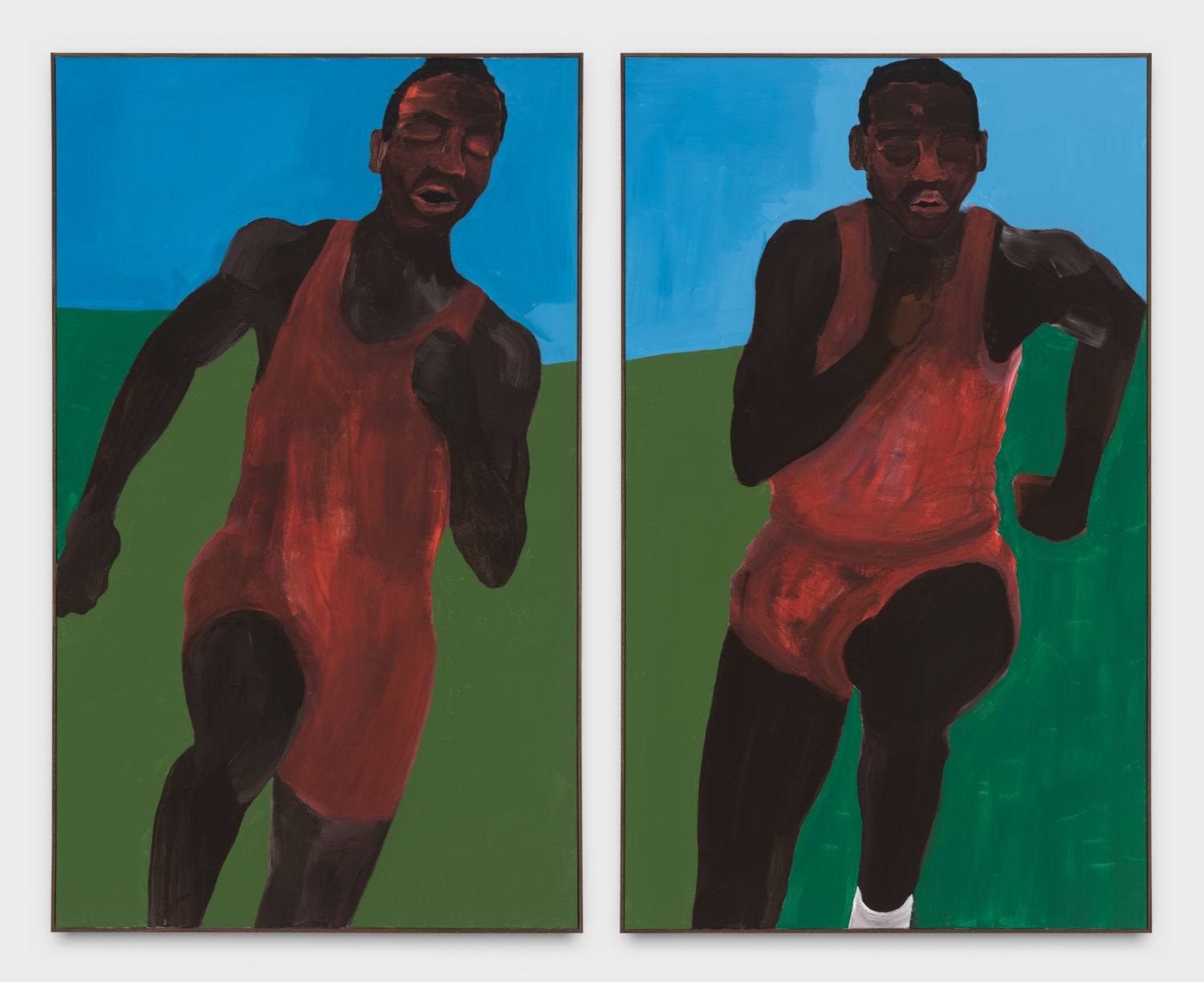

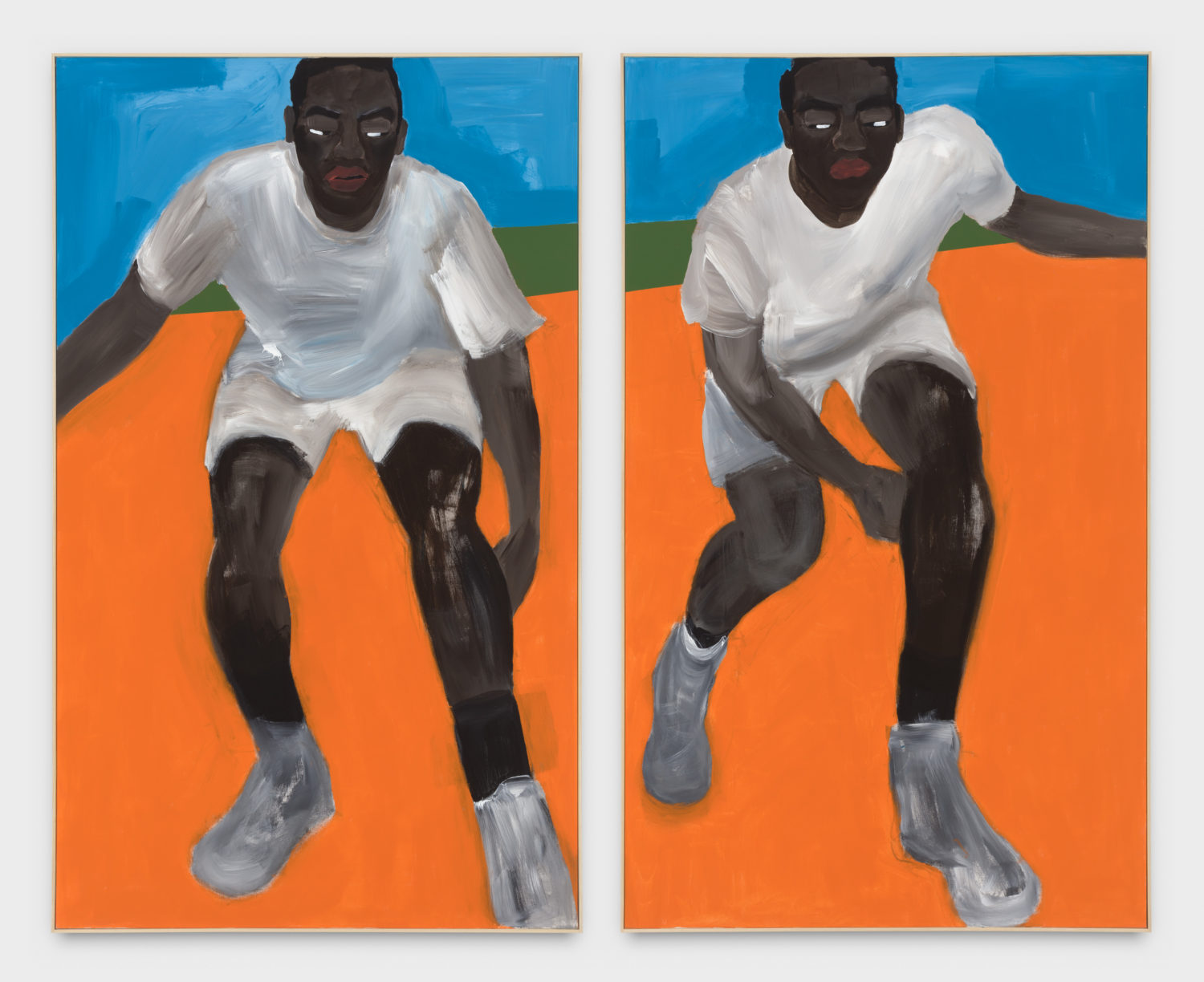

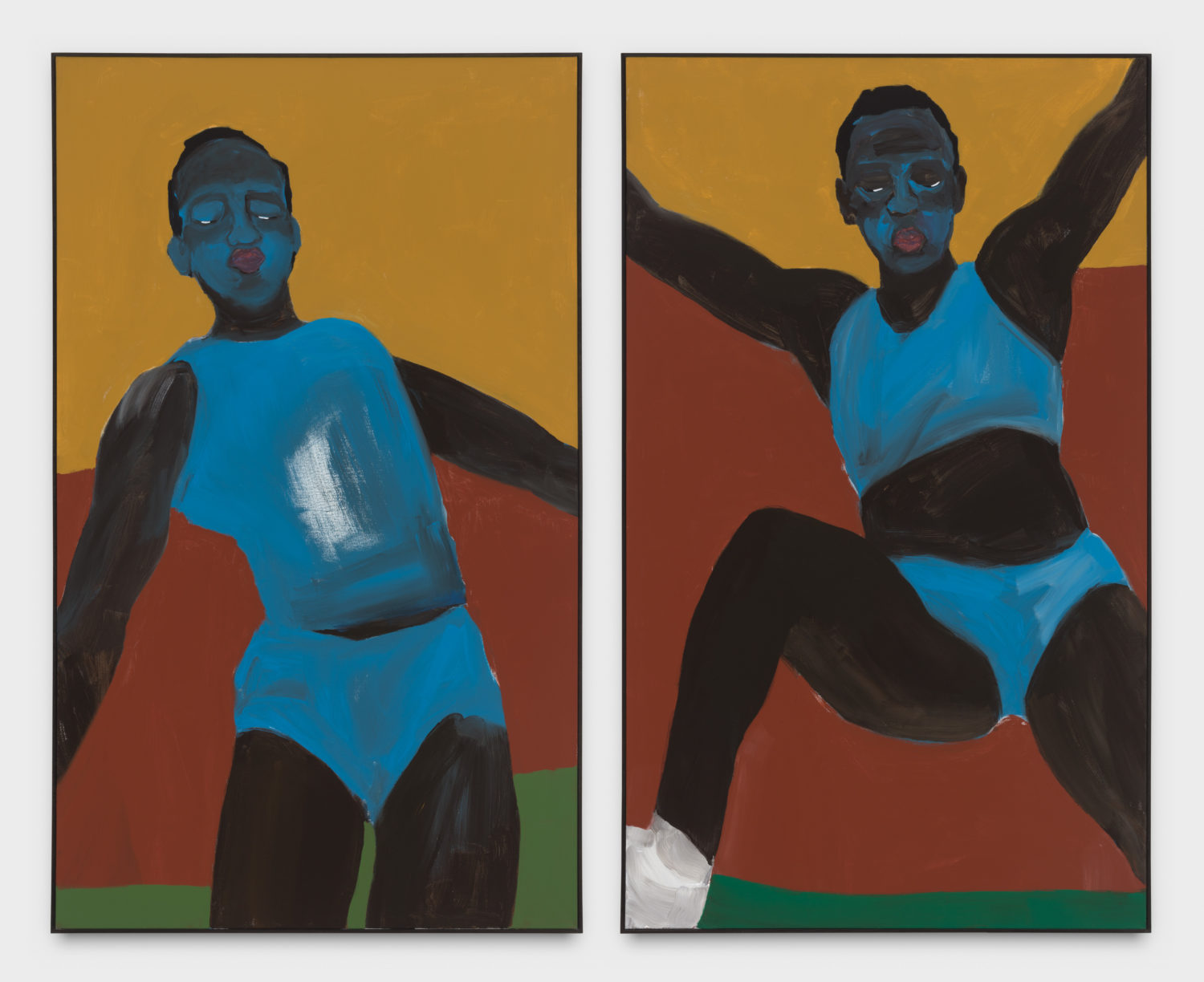

Interview: Painter Alvin Armstrong Questions Society’s Expectations Of Black Bodies

By Something CuratedOpening next month, 5 May, New York’s Anna Zorina Gallery is set to present To Give and Take, a solo exhibition of new works by New York-based artist Alvin Armstrong, curated by Stephanie Baptist. The upcoming show brings together a series of characters, alone and paired, stationary and in motion, to interrogate the vulnerability of Blackness in America. Tightly cropped portraits and towering figures are placed in unidentifiable backgrounds, raising questions around masculinity, gender and even self-determination. Black excellence in the form of athletic prowess is juxtaposed against references to societal and police violence. The artist explains, “Athleticism is used to showcase the ways in which Black bodies are often fetishised for entertainment. Black people in this country perform at optimal levels, and the work interrogates the way society conditions Black people to believe sports are the only viable pathway to obtain some form of safety from the inequities of Black American life.” To learn more, Something Curated spoke with Armstrong.

Something Curated: Can you give us some insight into your background and how you became interested in painting?

Alvin Armstrong: I feel like most of my life, I’ve been in search of something. I tried out many different careers before painting. From working with young people to the military to most recently being a licensed acupuncturist. As I was approaching graduation from acupuncture school, I started grappling with the fact that I didn’t see myself as a clinician. I was asking myself whether I could support my patients with their health, when I wasn’t centring my own health. In May 2018, I decided to get sober. Once I put down old habits, I was left with an abundance of time. Three months into being sober and after an inspiring trip to the Brooklyn Museum, I thought I’d try painting for the first time. I immediately became obsessed with it and was consumed by the desire to get better. From that first day, it’s been my everything and I’ve poured my heart into it. I believe I’ve finally found the thing I’ve been searching for all this time.

SC: What is the thinking behind the selection of works included in your upcoming exhibition?

AA: The pieces for To Give and Take were painted specifically for this exhibition from November 2020 through February 2021. When I started, I was pushing myself to convey more vulnerability in my work and be more expressive. I was and am always moved by stories of racial inequity in this country and found myself painting Black men in particular in moments of stillness in what could be seen as fear or vulnerability. Weeks later, I was compelled to paint Black athleticism or Black excellence, which has often been a theme in my work. Eventually these two concepts collided. What is often celebrated and revered about Black athletes, their power, their speed, their strength, are things that are seen as threats to society if the athletes’ uniform isn’t present. Those same attributes have been the cause of death for unarmed Black people in America. The title of the show To Give & Take is an attempt to speak to that. We give so much and yet so much is still expected and taken.

SC: Could you expand further on your exploration of Blackness in America, particularly through your representation of athletes?

AA: I am multi-racial, specifically, Black, White and Japanese but I learned at a very young age that I’ll always be seen, first and foremost, as a Black man in this country. I’m inspired by that. We’ve been misrepresented, erased, and undervalued for centuries but Black American culture is beautiful and it’s deserving of love and reverence. Painting from that point of love and reverence is what gets me up in the morning. I paint athletes because I am an athlete and I connect with the determination, the commitment and the showmanship of sport. I feel that sports are the closest thing to a meritocracy in this country. Of course there are still so many racial politics at play. But at the end of the day, the fastest, strongest, or most athletic person wins, which is why it’s often seen as one of only a few paths to success in Black America.

SC: How do you think about using colour?

AA: I try not to overthink colour. I listen to my intuition and I choose them as I’m painting. The background is usually last. Sometimes I’ll finish a painting and if the colour seems wrong, I’ll completely paint over it with a new colour until it feels right. If I use any kind of reference imagery, either it’s black and white or I’ll edit it to black and white in order to choose my own. Colour is very important to me.

SC: How has the pandemic affected your way of working?

AA: To be honest, I’m obsessed with painting and I’m a workaholic. Painting was my obsession before COVID-19 but the pandemic’s restrictions cleared out what little distractions were left. It’s increased my intensity to produce new work, because I only arrived at painting and entered this industry in my late 30’s, I’m hyper focused on my practice.

SC: What do you want to learn more about?

AA: I want to learn more about history, specifically my own. There are huge gaps in my family history on both my mother and father’s side. My paternal grandmother migrated from the south to Los Angeles but we don’t know much about her parents. My maternal grandmother came to America from Japan after the bomb dropped and was severed from her family. For so long I was seeking, to determine what I wanted to do and who I wanted to be in this life and that pulled me away from understanding where I came from. Now that I understand my purpose, I feel a strong urge to turn around and investigate my family history. Learning more about my history could help me learn more about myself.

Feature image: Detail from Alvin Armstrong, Track & Field, 2021. Courtesy the Artist, Medium Tings & Anna Zorina Gallery, New York