The 70s Collective That Laid The Foundations For Intersectional Feminism

By Something CuratedActive between 1974 and 1980, the Combahee River Collective was born from a sense of dissatisfaction that both the feminist movement and civil rights movement did not address the needs of Black women and queer people. The collective joined together in the early 70s, seminally publishing The Combahee River Collective Statement, a key document in developing contemporary Black feminism. Their name came from founding member Barbara Smith, an author who played a significant role in building Black feminism in the United States. Wanting to name the collective after a historical event that was significant to Black women, she took inspiration from an action on the Combahee River that was organised by Harriet Tubman on 2 June 1863, freeing more than 750 slaves.

Smith and her cofounders, who attended the inaugural regional meeting of the National Black Feminist Organization (NBFO) in New York in 1973, became the foundation for the Combahee River Collective with their efforts to build an NBFO chapter in Boston — the NBFO was formed by Black feminists reacting to the failure of mainstream feminist groups to respond to the racism that Black women faced in the US. In her 2001 essay, “From the Kennedy Commission to the Combahee Collective,” historian and African American studies professor Duchess Harris states, in 1974 the Boston collective “observed that their vision for social change was more radical than the NBFO,” and as a result, the group opted to branch out independently as the Combahee River Collective.

Members of the group, including Smith and Demita Frazier, felt it was critical that the organisation address the needs of queer Black women, alongside Black feminists at large. Together, the group composed a powerful statement, facilitated by regular meetings and numerous retreats. In 1977, the collective released The Combahee River Collective Statement. The document remains one of the most compelling written works produced by Black feminists to date, highlighting an existence of intersectionality that other texts before it scarcely broached. It effectively relates societal problems specific to women and Black people, such as sexual and racial discrimination, and homophobia, offering a multifaceted lens on reality.

While the collective was not made up entirely of queer Black women, co-founder Frazier, in a 1995 interview with Sojourner: The Women’s Forum, noted, “In fact, most of us who were the founding sisters were lesbians or in the process of coming out: but there were heterosexual women who quickly joined us.” Frazier described many of the collective members as “refugees” from other movements — homophobia and misogyny was prevalent within the civil rights movement, and racism, propelled by a lack of diverse perspectives, was not uncommon in the feminist movement. Alongside Smith and Frazier, central members of the group included poet Audre Lorde and writer and educator Cheryl Clarke.

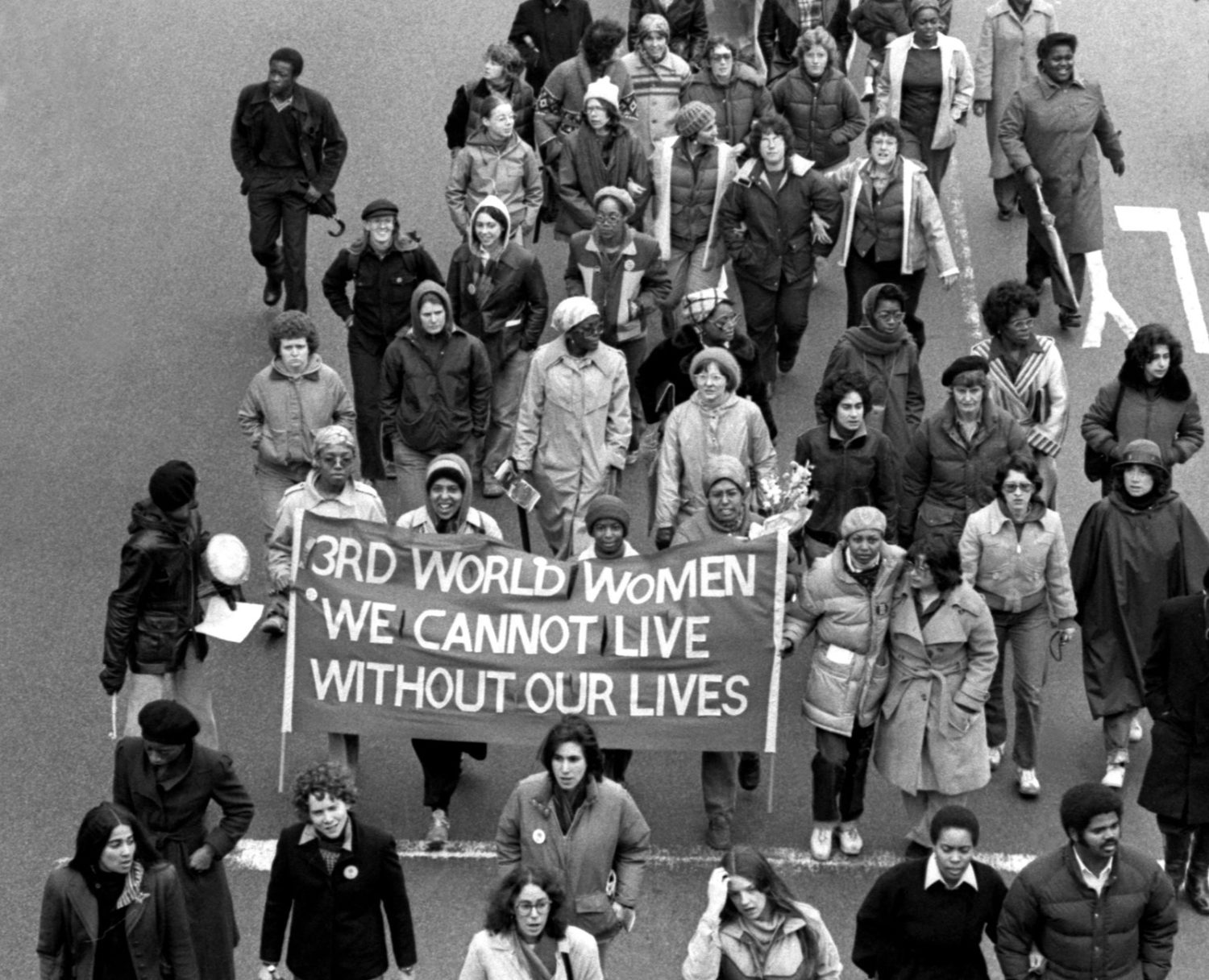

The collective were actively engaged in political struggles across Massachusetts, including desegregation in Boston schools and community campaigns against police brutality. “We believe that sexual politics under patriarchy is as pervasive in Black women’s lives as are the politics of class and race,” The Combahee River Collective Statement reads. “If Black women were free, it would mean that everyone else would have to be free, since our freedom would necessitate the destruction of all systems of oppression.” In 1979, twelve black women were murdered in Boston within the span of five months. Media coverage of the murders was minimal and there was no acknowledgement from the police that the murders were sexually or racially motivated.

Raising awareness and providing resources, the Combahee River Collective published a series of pamphlets condemning the murders, highlighting the racialised and sexual violence faced by Black women. At this moment, the collective became increasingly active, mobilising communities to protest the Boston Police Department and the media handling of the tragic murders. This culminated in a momentous march on 28 April 1979 at the Boston Common. Shortly after, the collective held their last network retreat in 1980, and disbanded the same year. Their work, and in particular their statement, remained fundamental in shaping the future of Black feminism, as well as, more broadly, identity politics today.

Currently open and running until June 2021, Boston Center for the Arts presents Combahee’s Radical Call: Black Feminisms (re)Awaken Boston, a multi-platform curatorial project co-curated by Arielle Gray, Cierra Peters, and Jen Mergel, and stewarded by the wisdom of original Combahee River Collective member Demita Frazier. The project takes the form of a series of public installations and programmes that re-enter the vital legacy of Black feminism, archives and the written word in Boston.

Feature image: Members of Combahee River Collective at the March and Rally for Bellana Borde against Police Brutality (Boston, 15 January 1980). Photo: Susan Fleischmann