A Cosmic Soup Of Fantasy & Industry

By Something CuratedFluctuating between the secular and the religious, ‘Underpinned by the Movements of Freighters’ is a curatorial project led by artist Joe Moss inside The Florence Trust, St. Saviour’s Church, London. Featuring a symbolic number – that of Greco-Roman Gods and Christian apostles – Moss merges twelve emerging and mid-career creators from varying backgrounds, careers and cultures. A culmination of existing pieces in tandem with new works, the exhibition functions as an intervention to the historical atmosphere of the ecclesiastical space, encompassing economy, myth and science.

‘Freighters’, denoting a cargo ship made to carry goods in bulk, sets its tone. Shipping as metaphor is expanded to the notion of transmutation where items are transported and radically altered in the process. This fittingly describes the prime focus; movement. Opening at the beginning of July, we are starting to unpack what it means to return to the bustle of the everyday. Our lives were held at a standstill, leaving many of us no choice but to indulge in personal fantasies. In this show, mobility is both fantastical and industrial, a union suggesting that they are not as different as they may appear.

The Florence Trust is a Romantic era church with original art of the Romantic period – an optimal framework to puncture the specificities in folkloric heritage. The goal is to acknowledge the space it sits in while simultaneously disrupting it, the caveat being that there cannot be intrusive alterations due to conservation laws. This drove the curator to strategise around these legalities. Distinguishing the exhibition from the church by employing materials foreign to its makeup, the cathedral has sunk back into a looming illusion.

Moss characterises the show as a “cosmic soup” of intertwined elements. Citing the nuclear family as a fundamental mythology that has shaped Western civilisation, it intends to convey how myths become convoluted with broader histories. The synthesis of such is no easy feat. Bridging nineteen interdisciplinary artists and writers is a testament to Moss’ vested interest in communion. The word captures the intimate act of shared spiritual wisdom and the service of Christian worship. Both regard faith in community as a central tenet.

When entering the behemoth of the church, we are faced with Gabriel Birch’s ‘Second Skin’. This installation lights the entrance to the project space in blue and pink, supplying a permeating, otherworldly hue. The metal, organ-like fragments dangling from the mechanical rail reverberate a sinuous quality. Birch’s deft selection of metals are explicit allusions to industry and urbanism. Water (a source of contamination, catastrophe and life) condenses of the surface of the sculpture, both beautifying and dirtying its potency.

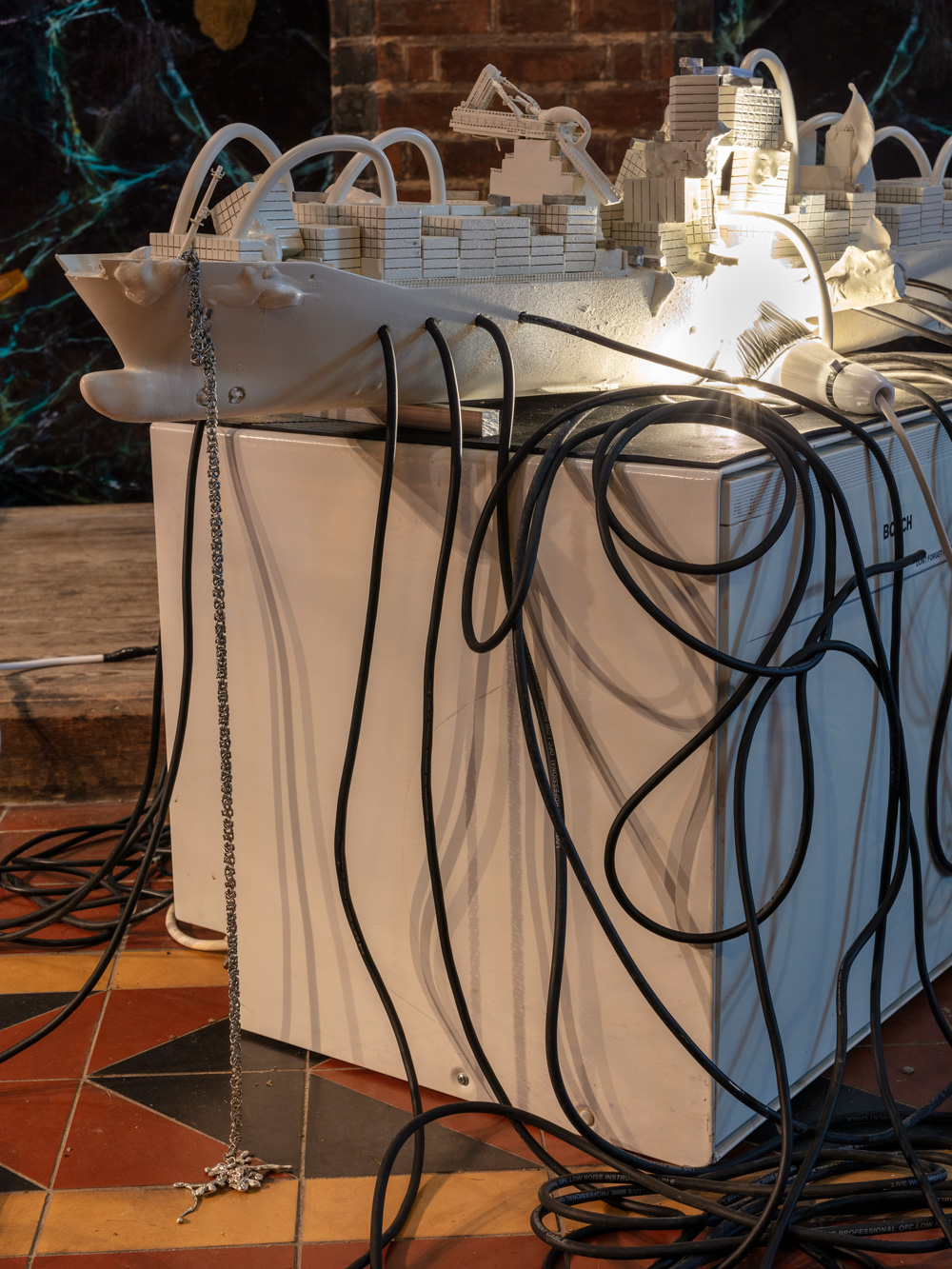

In the juncture between the walls, Bryan Dooley’s ‘Data Barge (Emma)’ is a ship maquette echoing the show’s title. Dooley pulls from his research into dormant patents, currently owned by Google, that relocate data farms to oceanic waters. Here, cold storage (preserved computer information) takes the physical form of the boat. In all its dystopian possibilities, it plays on the inevitable disaster that stems from immense technological development. The cables, denoting the transmission of intel, descend into an entangled chaos.

Facing the boat is one of the largest paintings in the show, Kemi Onabule’s ‘Midnight’. The canvas is a verdant utopia, an idealistic vision of what a greener future would entail. The artist draws from the African Ifá deities, apparent in the swollen breasts of her colorful, featureless figures. Onabule reinterprets a cosmos no longer burdened by capitalistic demands; the lush, undamaged vegetation depicted facilitates the reinvention of humankind, when all indicators of progress have become defunct.

One of Jane Davies’ ceramic sculptures of a face is smaller than a credit card. It is embellished with beads and thread and personifies the exact moment when one thing emerges from another. Davies is somewhat of an ‘outsider’, with no formal training. This bleeds into her preference for accessible mediums – notably beads, clay and wire. This modest but mighty portrayal is informed by pareidolia, the psychological phenomenon of assigning facial characteristics to random patterns and objects.

On a contiguous wall is yet another petite work, this time by Luke Samuel, titled ‘Row’. Though its close-up stylisation makes it an arguable abstraction, the semblance of interior space is visible. Boundaries are loosened on canvas with the tenderness of Samuel’s brush, delineating soft cushions that absorb each other’s weight. The hazy palette mimics blurry sight, as if peering at the room from a sheer curtain. The artist invites the spectator to become privy to something they were not supposed to see.

Away from the conflux lies Susan Jacobs’ prehistoric science lab. Abiogenesis, a theory of life forms having evolved from inanimate matter, is her main reference. Still a debated topic in academic circles, the principle is in folklore. Jacobs’ installment alludes to a 16th century recipe for creating scorpions out of bricks, exposing the “absurd origins of scientific method”. The blocks are subtly activated by a mechanism infused with holy basil, situating this outlandish array at the convergence of clerical belief and scientific inquiry.

Sophie Goodchild’s bronze-casted toad, is pulled between Jacobs’ and Dooley’s proposals, buckled and squashed by the weight of the intermediacy. Another surface connection to Jacob’s work comes from the ‘frogs’, the hollow cavity in bricks. Goodchild’s production is illuminated by witchcraft, as well as folkloric tales of the fantastic and absurd. The intricately crafted squashed toad, rendered meek by the imprint of a foot, was believed to personify the Devil in Medieval English fables.

Ajl a Yi’s ‘Limbic Juice’, a latex spill trickles from a pillar which impressively juxtaposes the formality of the site’s ancestry. Adjacent to it are two screens displaying Yi’s 3D animation of a futuristic symbol, referring to a community that does not yet exist. These are complemented by ceramic sculptures of new biological forms. The installation’s engagement with the Gothic building subverts its ideals and departs from the internal struggle of the ‘hero’, instead honing in on potential for new modes of collective being.

Alix Marie’s fragile glass limbs adapt to the immaterial emanations of the religious space; disembodied hands in a sickly shade of green arise from pink salt. Marie maximises the potential for three-dimensionality and crosses the threshold demarcating photography and sculpture. The artist views skin as a repository of secrets and taboos: the transparency of the parts both objectifying and complicating the vulnerable body, rendering it abject.

Ashleigh Fisk’s monoprints, influenced by her upbringing in the countryside, reveal the “darker side of folklore”. Though devoid of visible bodies, the ominous presence of someone is implied. Reengaging with nature became a refuge for many during the past year in isolation – but what if this routine turned sour? The river overflows the scene while the shriveled up trees bear witness to nature’s primal scream.

One of the largest works is Salome Wu’s steel blue canvas, ‘Oaths’, which examines otherworldliness formed through the interplay of grounded reality and the unseen. From a nonlinear sea of abstraction, a moon deity takes over the composition. Wu welcomes a sense of mysticism and sublimity in her depictions, while concurrently aspiring to heal. The color blue has historically been associated with loss and trauma, but here it is transformed into a soothing, glaucous melody.

The dark wallpaper, meticulously designed by Scott Young, is the backdrop of the paintings as well as one of his own. Young displays a still life with similar imagery to his upholstery, toying with the high status of painting in the space – yet another tradition inadvertently upheld. His custom wallpaper is a gateway highlighting the haphazardness of such distinctions. Young contradicts cultural hierarchy that refuses to validate the decorative, an outcome of mass-production taking over craft.

Alongside the exhibition, a limited-edition zine containing consolidating essays, poetry and prints that further illustrate symbiosis of lore and industry. Sabeen Chaudry investigates the history of salted caramel’s transition from fantasy to ubiquity, Cole Denyer remarks on the anachronism of London’s commuter belt, Nina Davies looks toward the myth of intent in slo motion video, Richard Phoenix ponders on the myth of abnormality, Stephanie Pollard deep- dives into the significance of chainmail, Sherie Situaze looks at quantum mechanics as a way of combating colonialism, and Huhtamaki Wab contributes an original animistic print.

We have been led to believe in and espouse the necessity of fixed binaries but times are changing. Visitors are encouraged to navigate the show by instigating the artworks comparatively, revealing a rich tapestry of history whilst allegorically reenacting the key myths. Mythologies contain ethical values, coding their morality into culture by storytelling – in spite of their rudimentary ridiculousness, they are essential to the formulation of modern identity.

Curated by Joe Moss, ‘Underpinned by the Movements of Freighters’ at The Florence Trust, St. Saviour’s Church, London runs until 16th July.

Words by Vanessa Murrell / Photography by Theo Niderost / Feature image: Ajla Zihan Yi, Limbic Juice