Surrealism In Egypt: The Story Of Cairo’s Pioneering Collective Art et Liberté

By Something CuratedIn March 1938, the Egyptian poet and critic Georges Henein and a small group of friends interrupted a lecture in Cairo given by the Alexandria-born Italian Futurist F.T. Marinetti, a supporter of Mussolini. Six months later, Henein, along with the Egyptian writer Anwar Kamel, the Italian painter Angelo de Riz, and 34 other artists, writers, and activists, signed the manifesto “Long Live Degenerate Art!,” birthing the collective Art et Liberté. The manifesto’s title, which borrowed the label the Nazi party gave to art they disapproved of, reflected the group’s refusal of fascism, nationalism and colonialism. Operating prolifically for a decade, they provided a frustrated generation with a platform for cultural and political reform. When Art et Liberté was initiated it was against a backdrop of highly conservative state-endorsed exhibition practices, imbued with nationalist thought. The collective unequivocally rejected the alignment of art with political propaganda.

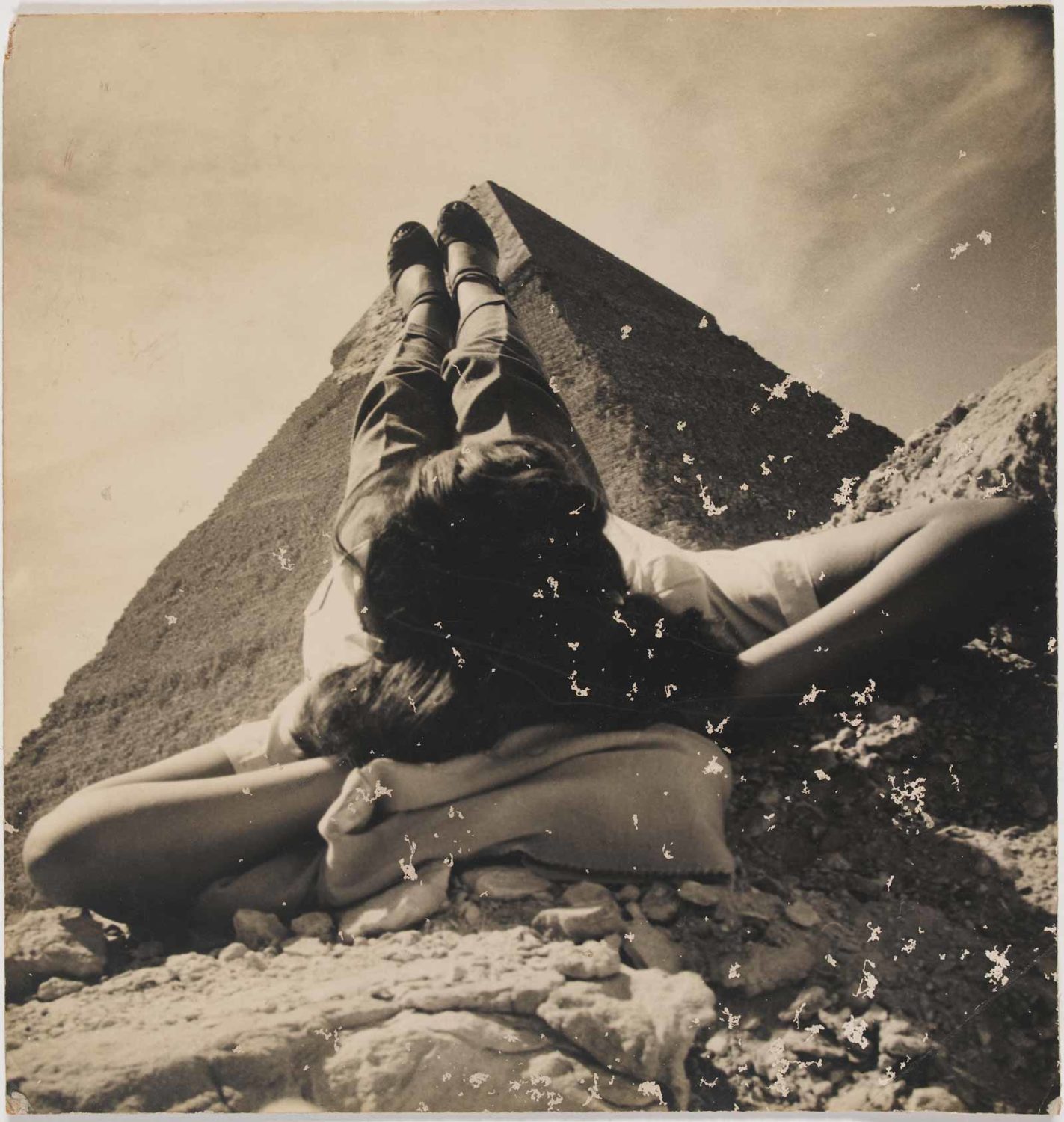

Redefining ideas of what surrealism was, the Art et Liberté group was as much globally engaged as it was entrenched in local artistic and political concerns. Taking an active role within an international network of surrealist writers and artists, they established a contemporary literary and illustrative language. The group’s resolve to affect social and cultural change was only fortified in the face of fascist ideologies that, beyond their firm grasp over Europe, had been on the rise in Egypt since the early 1930s. Though Cairo was not on the frontlines of war, Egypt, under on-going British political influence, put its national resources, along with its entire infrastructure, at the disposal of the British. By 1941, 140,000 soldiers were stationed in Cairo alone, and troops and tanks swarmed the city streets. A profound engagement with the war, and the destruction that it caused, informed the whole spectrum of Art et Liberté’s output.

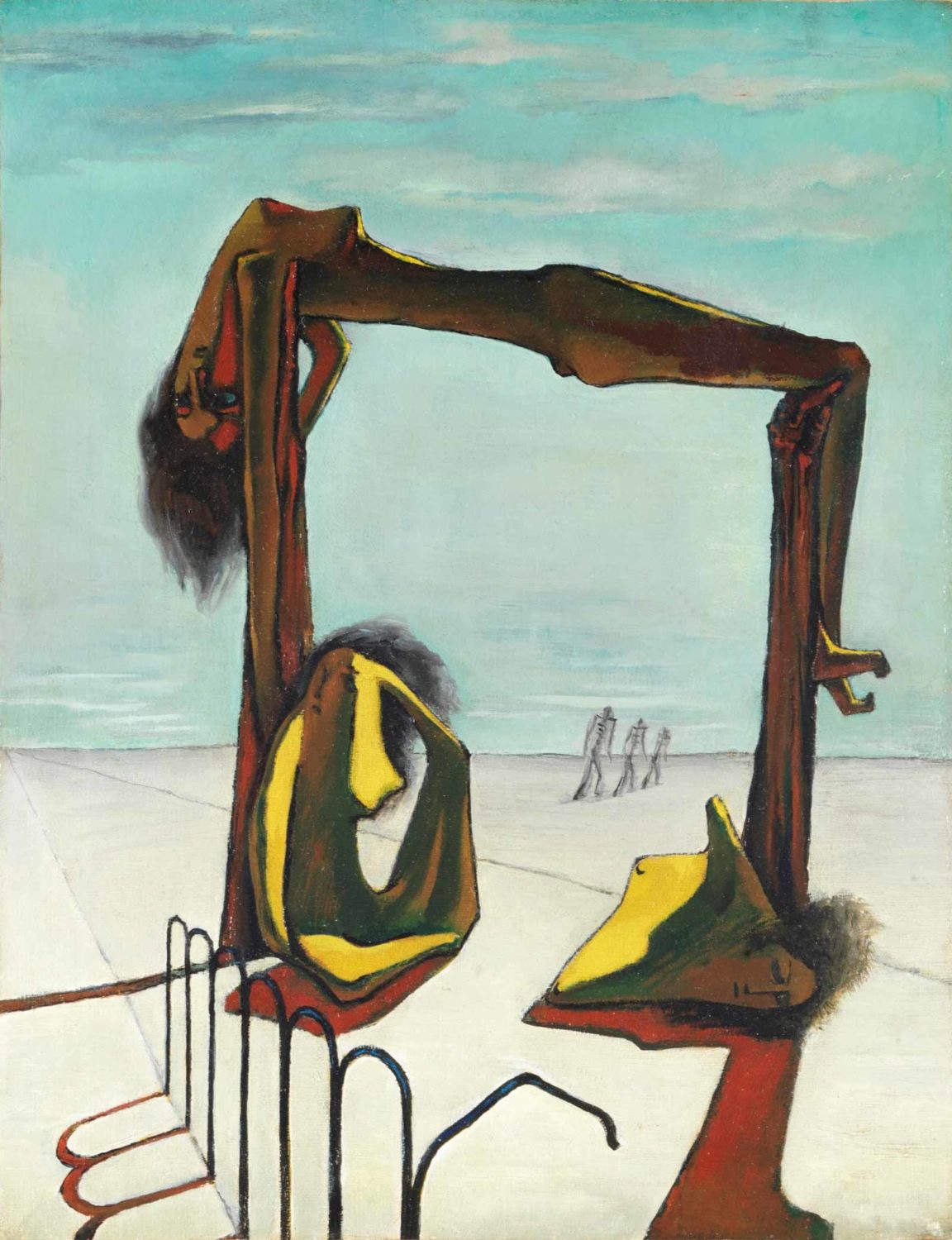

While Art et Liberté was active, Cairo faced extreme inequality. Most of the city’s wealth was held by a small percentage of feudal landowners and business magnates, while more than half of the population, mostly rural labourers and urban workers, endured poverty. The collective believed that this unfair distribution of resources was maintained by the prevailing economic, social and cultural mentality, manifested in broader cultural trends, such as the championing of national symbolism and realism in visual art. In these traditional styles, bodies were portrayed in an idealised fashion. In contrast, Art et Liberté painted deformed, dismembered or distorted figures, and the motif of the fragmented, or “emaciated body,” as Art et Liberté called it, became a site of social as well as artistic protest, illustrating the distinct economic injustice that plagued their society.

An essential feature of Art et Liberté’s creative expression is the close relationship between their visual art and literature. Frequently, a poem by one of the group members would provide the subject matter for another member’s painting. Similarly, a painting would inspire certain scenes in one of the group writers’ short novels. Several Art et Liberté painters were called upon by their fellow group writers to illustrate their publications, for example. Between 1940 and 1943, Fouad Kamel embarked on a series of portraits where a woman slumbers in a meditative trance-like state. In most of these, two objects continue to appear: a candle and a marijuana plant. Kamel’s paintings borrow many literary images that recur in Albert Cossery’s compelling love story, The Girl and the Hashish-Smoker, first published in Cairo in 1940. This dialogue between painting and literature perfectly demonstrates the interdisciplinary nature of Art et Liberté’s work.

Leading group member, theorist and painter Ramses Younane, reflected on surrealism as a movement in crisis. Recognising two types of surrealism, the first, epitomised by Dalí and Magritte’s fantastical juxtapositions, was considered by Younane as pre-meditated, leaving no space for the uncontrolled imagination. The second, consisting of automatic writing, pioneered by Breton and adapted to drawing, was deemed egotistic and disregarding of collective empowerment. Younane saw a need for a new type of surrealism, which he dubbed “subjective realism.” According to this new definition, artists could freely adopt the formal style of their liking or reflect on any subject they were interested in – hence “subjective.” Seeking to make use of symbols and settings that were easily recognisable by the public, they drew from a wide range of sources. These could vary from an ancient Pharaonic motif or a desert landscape, to a familiar architectural edifice – providing the “realism.”

Several younger Art et Liberté members cofounded an independent collective under the name of the Contemporary Art Group in 1946. The group remained active until the mid-1950s and a few of its members, such as Abdel Hadi el- Gazzar, Hamed Nada and Samir Rafi, would later become some of Egypt’s most prominent modern artists. From the late 1940s until the early 1960s, the question of how art can be made authentically Egyptian, furthered by the Revolution of 1952, became a principal concern for artists and intellectuals alike. The Contemporary Art Group, moving away from surrealism, turned instead to a language consisting of symbolic iconography, becoming perceived by the public as a movement that established the first truly modern Egyptian art. The main artists of Art et Liberté, who had separated in 1948, critiqued the Contemporary Art Group, who returned to more traditional realist means, as becoming representative of a new form of nationalism.

Feature image: Mayo, Coups de Bâtons, 1937. Image courtesy: Private collection, Milan