Chilean-Peruvian Artist Ivana de Vivanco Gives Voice To The Overlooked Stories Of Nonconforming Women

By Something CuratedCovering painting, sculpture and video, Chilean-Peruvian artist Ivana de Vivanco examines capitalistic development through a feminist viewpoint in her site-specific intervention Two Pennies for Myself and Tea (2021) at London’s SCAN – Spanish Contemporary Art Network, warping male-centred systems of dominance and exploitation.

Despite its misleading resonance of a nursery rhyme, the title extracts a segment of German philosopher Karl Marx’s book Das Kapital (1867), which outlines the shockingly abusive terms agreed by children for their work in the silk manufacturers of Bethnal Green, where the show is located. Once a land of commons that sustained forests and marshlands, the area soon transitioned into a crowded, urban and poor quarter. Spotlighting the disintegration of communal territories, de Vivanco paints the entire floor of the gallery in fluor green. Simulating an open expanse of luscious grass in all its glory, its glowy coating reflects the underlying hue back to those present, like an avalanche of contamination that melts into one’s face: aromas of algae, infection, poison, snot, slime, or vomit – this is a synthetic colour that contains such radiance that it can rip and link the space all at once.

The largest painting in the exhibition, Captain Ann Carter (2021), embodies an archetype against patriarchy. A vibrant enactment of the conflicting protests of English activist Ann Carter, the wife of a middle-class butcher. In the midst of the industrial depression of the 17th century, Carter led riots in Malden in defiance of the escalating price of grain, encountering the inevitable fate of execution for her significant role in the uprising, her presumption of leading men, and her self-entitlement of the male rank “Captain.”

Referring to herself as “a composition freak,” de Vivanco’s work renders a turmoil of intercrossing perspectives epitomised in each gesture and silhouette. Advancing past the open greenery, the picturesque setting is strained by diagonal tensions that expose the intricacies of power-relations. de Vivanco’s figures in flux are amassed in their disposition, yet detached in their gaze, as if caught mid-commute during rush hour. No longer consenting to starvation, a fierce female carries away half a bushel of rye in her apron. Her stuffed physique is painted – almost painfully – red, but she marches heroically at the prospect of feeding her family.

However she is not alone. As sunny as it might seem, a Native female companion wears a woven hat, protecting herself from the cold as she pours rye in a vessel. Her thick, braided hair parallels the interlaced chains depicted on the border, which are torn apart, implying a necessary step in the process of human liberation. Fuelled by the possibility of food, a sketched infant follows, whose sharply delineated hand is clasping the legs of Carter in a subtle indication of not wanting to be left behind. Engaged in the frontline are those often outdistanced from mainstream society: children, women, colonial subjects – the others – or as activist Silvia Federici signals in her book Caliban and the Witch (1998), those who are essential for keeping communities together and for defending noncommercial conceptions of security and wealth.

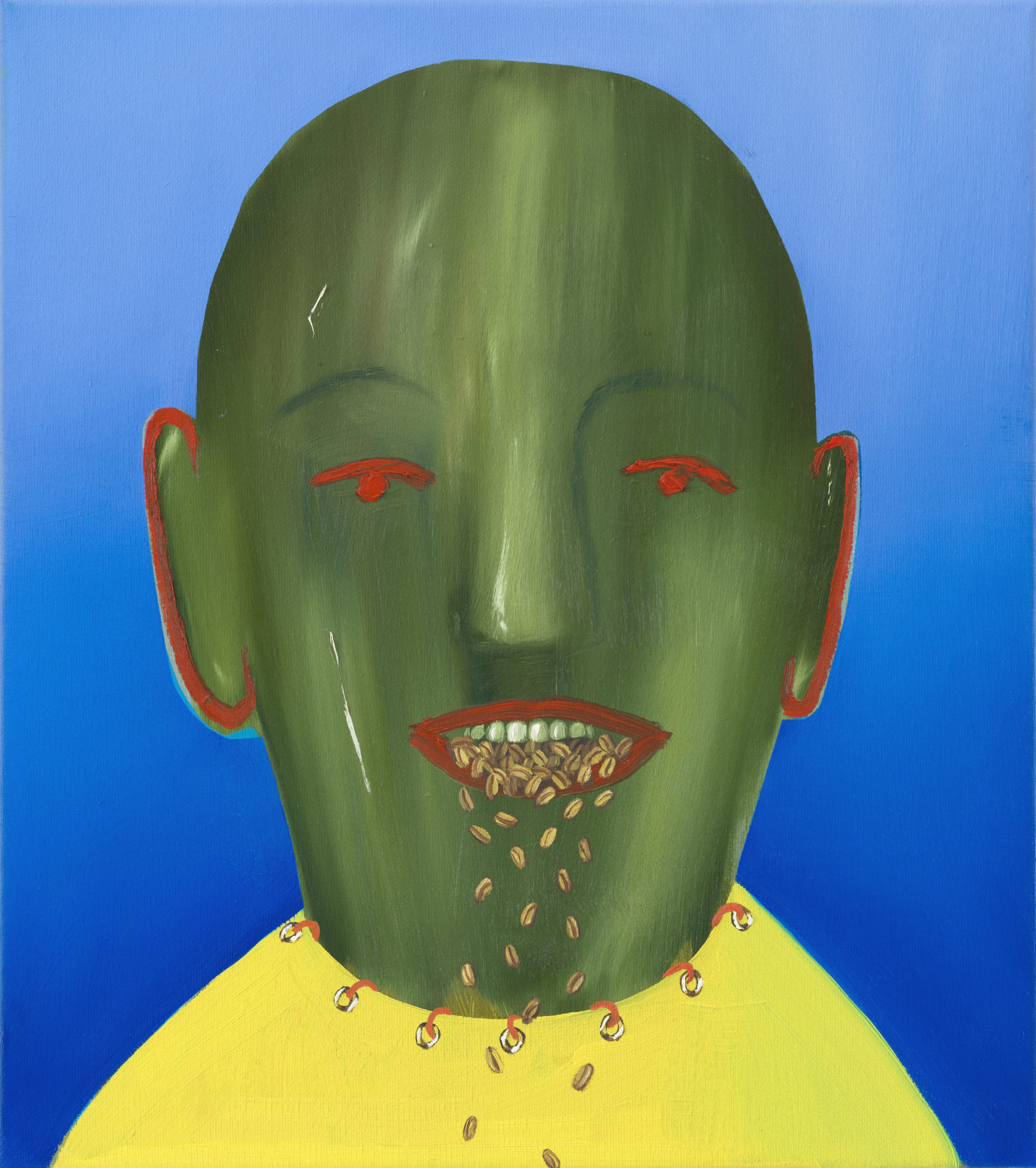

With a passive facial expression, an anonymous character crosses a fence in a state of complete coordination. His right palm is held upright towards the unlawful receivers in an attempt to stop them immediately from trespassing. Simultaneously amorphous and definite, his enigmatic profile is symbolic of “the establishment,” also referred to as the bosses, the influential politicians, the well-connected upper-class, those undetermined and yet so pronounced. In Headquarter (2021), the artist offers an intimate portrait of this invisible force. Modest in scale but monumental in authority, he devours grains with such intensity that they spill out of the canvas, pilling onto the floor.

Also reaching the bottom surface is a headless giant made of fabric and hair that hangs from the ceiling, whose disproportionate pendulous arms stretch too far away from its body. The fragmented sculpture Capital Distancing (2021) and its performed video evoke with humour the breach between labour and value, questioning philosopher René Descartes’ understanding of bodies as extended, transportation vehicles of our independent minds. Featuring a persona seated at a dinner table, her green-tinted bare head echoes the lost commons and makes an allusion to the witchcraft trials, where the women accused were shaved so men could search for “witchery marks.” Within the bourgeois tableware, the subject, who dresses in the same ridiculously long garment that is suspended in the room, is being fed wheat in an absurd, puppet-like process. The distance is further reinforced by de Vivanco, who states “the hands produce, but are so far from the body of the producer. Labour works, the golden hands take.” In this disembodied transaction, the artist finds common ground by transforming violent histories of controlled bodies into sites of resistance that refuse capture.

Ivana de Vivanco’s Two Pennies for Myself and Tea at SCAN Projects, London runs until 30 September 2021.

Words by Vanessa Murrell