Understanding The Inspired Architecture Of Bhutan

By Something CuratedCarved tools, weapons and remnants of large stone structures are indicative of Bhutan having been inhabited as early as 2000 BCE. Historians have postulated that the state of Lhomon – literally meaning “Southern Darkness” – or Monyul – “Dark Land” – a reference to the Monpa, an ethnic group in Bhutan and Arunachal Pradesh, may have existed between 500 BCE and 600 CE. The names Lhomon Tsendenjong – “Sandalwood Country” – and Lhomon Khash – “Country of Four Approaches” – have been found in ancient Bhutanese and Tibetan scrolls. A landlocked nation in the Eastern Himalayas, the Kingdom of Bhutan is bordered by China to the north and India on all other sides. The subalpine Himalayan mountains in the north rise from the country’s lush subtropical plains in the south.

In the Bhutanese Himalayas, there are peaks higher than 7,000 meters above sea level. Gangkhar Puensum is Bhutan’s greatest peak and is thought to be the highest unclimbed mountain in the world. The land consists mostly of steep mountains crisscrossed by a network of rapid rivers that form deep valleys before draining into the Indian plains. Much of early Bhutanese history is shrouded in mystery because most of the nation’s records were destroyed when fire ravaged the ancient capital, Punakha, in 1827. By the 10th century, Bhutan’s political development was heavily influenced by its religious history. Numerous subsets of Buddhism emerged that were patronised by the various Mongol warlords. Today, the country’s largest city, Thimphu, is its capital, home to some 115,000 citizens.

Bhutanese architecture remains distinctively traditional, employing rammed earth and wattle and daub construction methods, stone masonry, and intricate woodwork around windows and roofs. Traditional architecture uses no nails or iron bars in construction, and remarkably no planning on paper. Characteristic of the region is a type of castle fortress known as the dzong. Dzongs in Bhutan were built as strongholds and have served as religious and administrative centres since the 17th century. Traditional dzongs have only one entrance gate and every dzong has a central tower temple, which is surrounded by a courtyard. The walls of the dzong are characteristically slanted inwards and the structure’s windows are typically painted black, creating a bold contrast against the white walls.

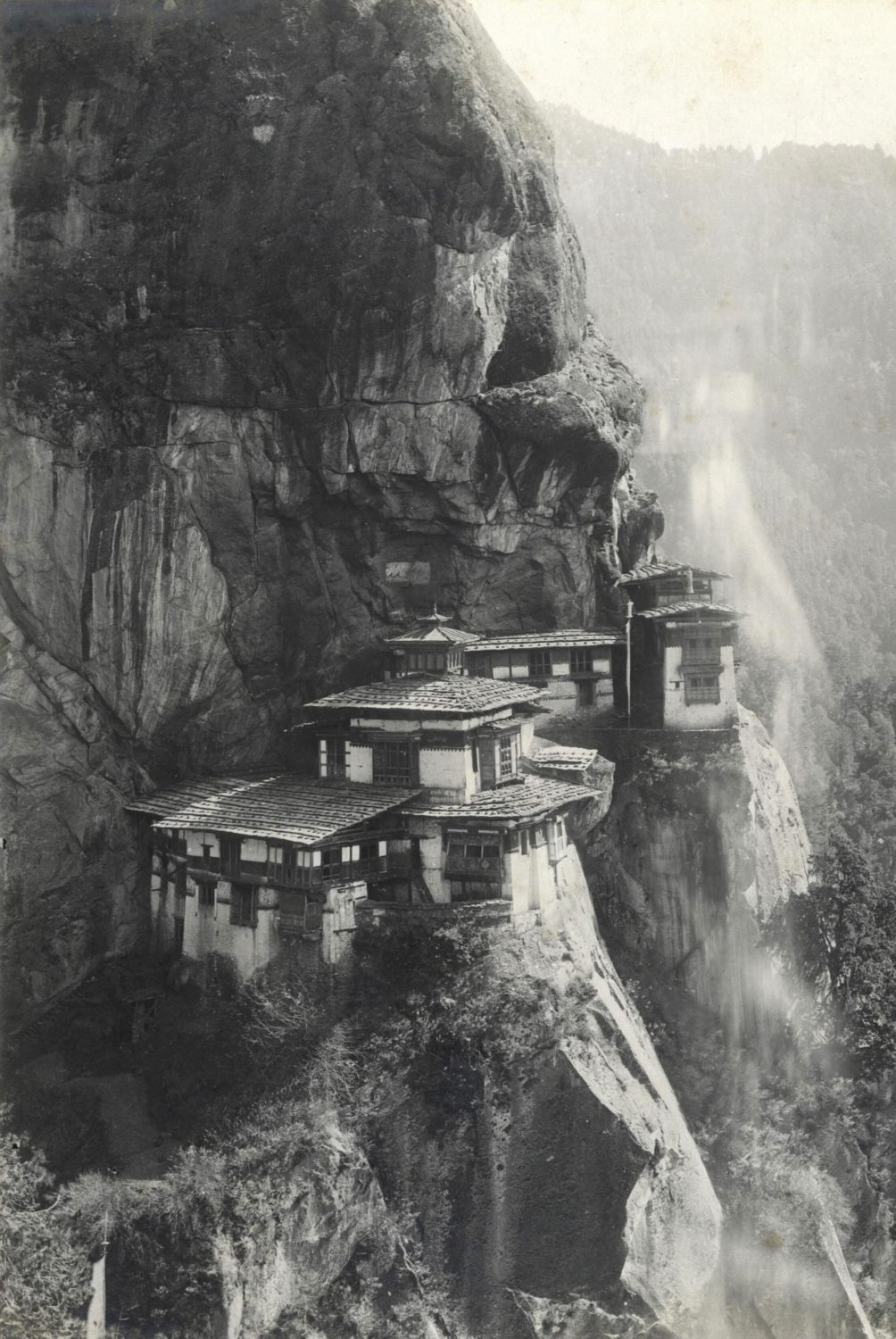

Paro Taktsang Monastery is one of the most significant symbols of culture and religion in Bhutan, situated high in the Himalayas. Its remote location centres around a taktsang – which means “tiger’s lair” in Tibetan – and is one of thirteen such Himalayan caves that were used for meditation by Guru Rinpoche, also known by Padma Sambhava. The temple complex at Paro Taktsang comprises four temple buildings and a series of eight caves. The buildings are connected by a network of tight stone walkways and a number of bridges, with the caves accessible behind the temple buildings. Like many important buildings in Bhutan, Paro Taktsang features stark white exterior walls and red shingled and golden roofs. The current buildings were constructed in the early 2000s after a fire broke out in 1998.

Owing to Bhutan’s dramatic topography, the majority of the country is connected solely by large wooden bridges. Traditional Bhutanese bridges make use of cantilevers, beams anchored to one bank and projecting horizontally to reach the other. Punakha Suspension Bridge, typically adorned with colourful prayer flags, is the textbook example of this. Linking Punakha Dzong to Shengana, Samdingkha, and Wangkha villages across the Tsang Chu River, this is one of the longest suspension bridges in Bhutan. For a roughly 520-foot-long structure, it’s surprisingly unwavering. Stabilising cables that taper off on both ends of the bridge provide a strong force of balance, while still allowing some inbuilt flexibility that enables the bridge to swing in strong winds.

As recently as 1998, by royal decree, all of Bhutan’s buildings are required to be constructed with multi-coloured wood frontages, small arched windows, and sloping roofs. Interestingly, many traditional structures feature paintings of phalluses. The story of this fascination with penises dates back to the 15th-century arrival of an unusual Tibetan Lama, a saint, named Drukpa Kunley. It is said that he shot an arrow from then-Tibet to locate a new land to share his teachings. The arrow landed close to the site of present day Chimi Lakhang in Punakha and led him to Bhutan. While searching for the arrow, he met a young girl who believed in his cause, and, gratified by her faith, he spent the night with her, “blessing” her with his offspring. Today, this unmistakable symbol of fertility continues to appear widely across the country’s architecture.

Feature image: སྤ་རོ་སྟག་ཚང་། Paro Taktsang (via Pinterest)