What Is Land Art?

By Something CuratedBorn out of the conceptual art movement of the 1960s and 1970s, land art expanded boundaries of art by the materials used and the site-specificity of the works made. At first, the materials utilised were typically taken directly from the works’ surrounding landscape, including the soil, rocks, vegetation, and water found on-site, and the sites of the works were often distant from population centres – though not always. While sometimes fairly inaccessible, photo documentation was frequently brought back to the urban art gallery. Concerns of the art movement centred around a rejection of the commercialisation of art-making with an emergent ecological movement; this coincided with the popularity of the rejection of urban living and in its place, an enthusiasm for the rural.

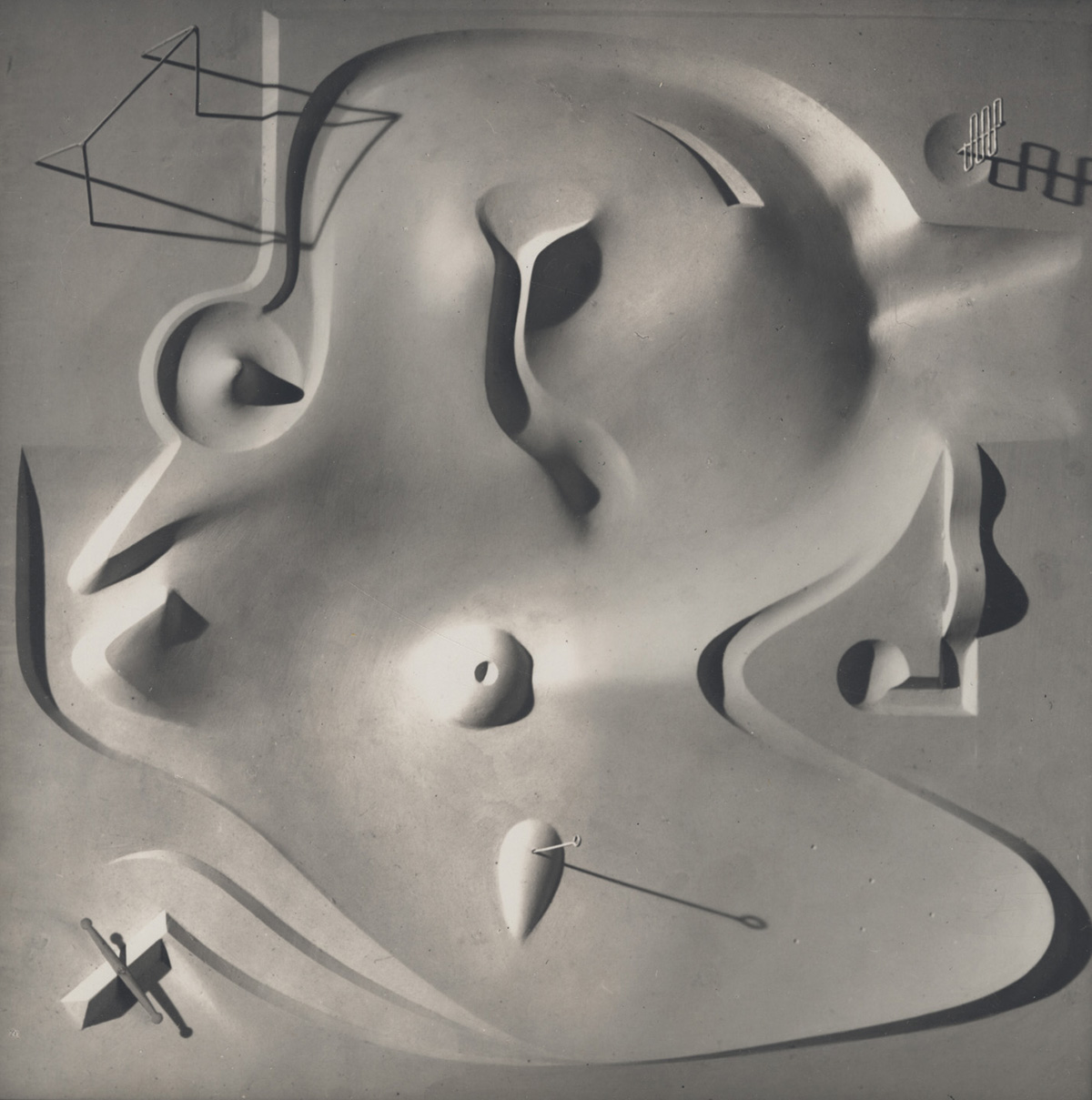

During this period, champions of land art questioned the museum or gallery as the setting of artistic activity and developed monumental landscape projects beyond the reach of traditional transportable sculpture. Land art was inspired by minimal art and conceptual art but also by modern movements such as De Stijl, Cubism, minimalism and the work of Constantin Brâncuși and Joseph Beuys. Many of the artists associated with land art had been involved with minimalism. Isamu Noguchi’s 1941 design for Contoured Playground in New York is sometimes interpreted as an important early piece of land art even though the artist himself never called his work “land art” but simply “sculpture.” Noguchi’s influence on contemporary land art, landscape architecture and environmental sculpture is evident in many works today.

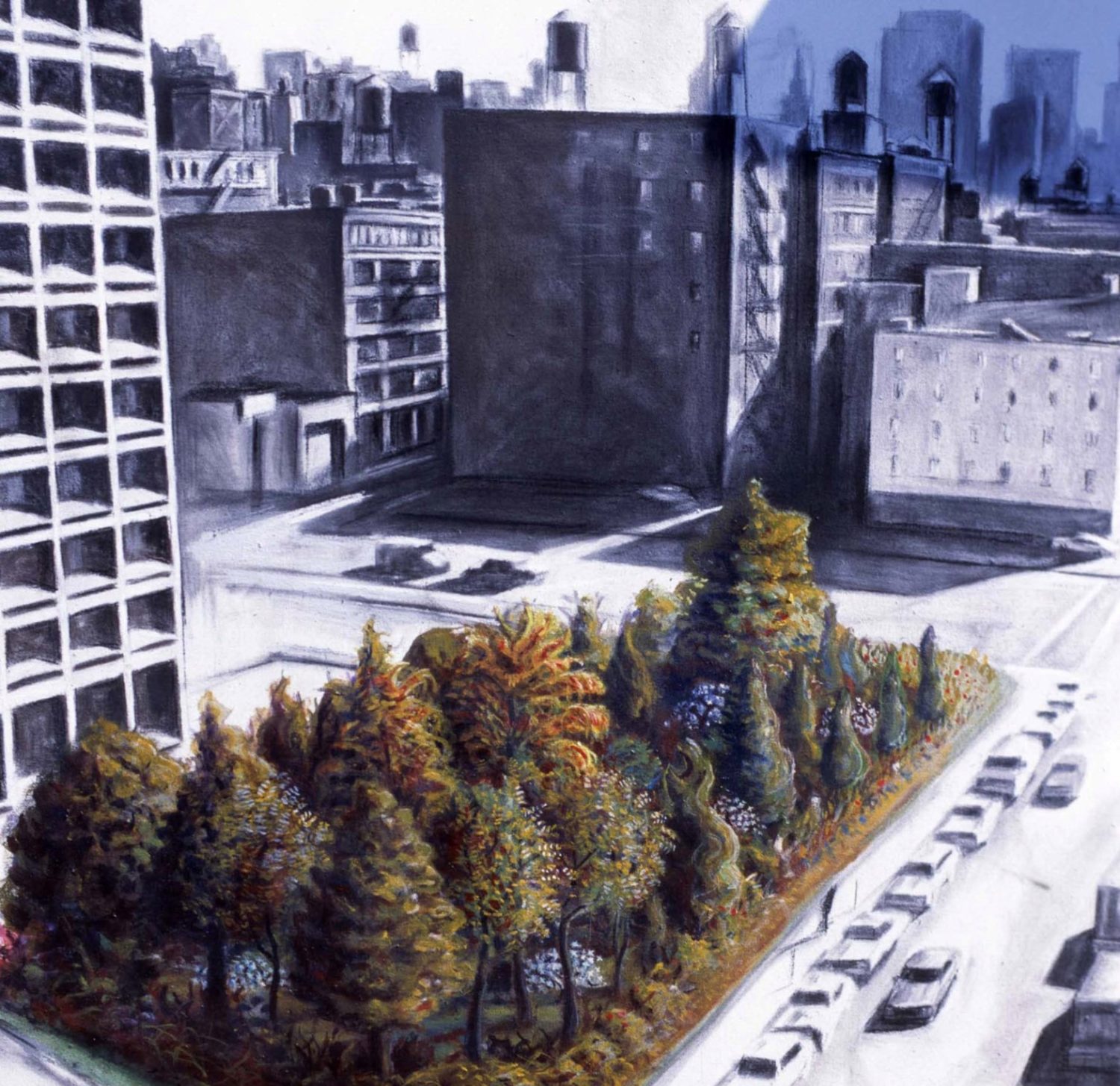

American artist Alan Sonfist brings historical nature back into the city. His most important work is perhaps Time Landscape, an indigenous forest he planted in NYC. He has also created several other Time Landscapes around the world such as Circles of Time in Florence, Italy documenting the historical usage of the land, and more recently at the deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum outside Boston. In 1967, the art critic Grace Glueck, writing in The New York Times,declared the first work of land art to have been executed by Douglas Leichter and Richard Saba at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture. The sudden appearance of land art in 1968 can be located as a response by a generation of artists mostly in their late twenties to the heightened political activism of the year and the emerging environmental and women’s liberation movements.

Perhaps the best known artist who worked in this genre was the American Robert Smithson whose 1968 essay “The Sedimentation of the Mind: Earth Projects” provided a critical framework for the movement as a reaction to the disengagement of modernism from social issues. His piece, probably the most famous piece of all land art, is the Spiral Jetty, 1970, for which Smithson arranged rock, earth and algae so as to form a long spiral-shape jetty protruding into Great Salt Lake in northern Utah. How much of the work, if any, is visible is dependent on the fluctuating water levels. Since its creation, the work has been completely covered, and then uncovered again, by water.

Cuban-born Ana Mendieta moved to the United States in 1961 at the age of 12, staying in refugee camps with her sister before relocating to Iowa. Mendieta’s father remained in Cuba as a political prisoner, and years of separation left the artist craving a deeper connection with the world around her. This childhood trauma permeates her seminal Silueta (Silhouette) series, produced between 1973 and 1980, in which the artist physically embedded her body into the landscape. For these “earth body” works, Mendieta would cover herself with blood, fire, flowers, and feathers, and push herself into the ground until she left her mark. Her flesh touched beaches, archaeological sites, and Mexican alcoves, among other locations, in radical gestures that combined shamanistic rituals, performance art, and the natural world.

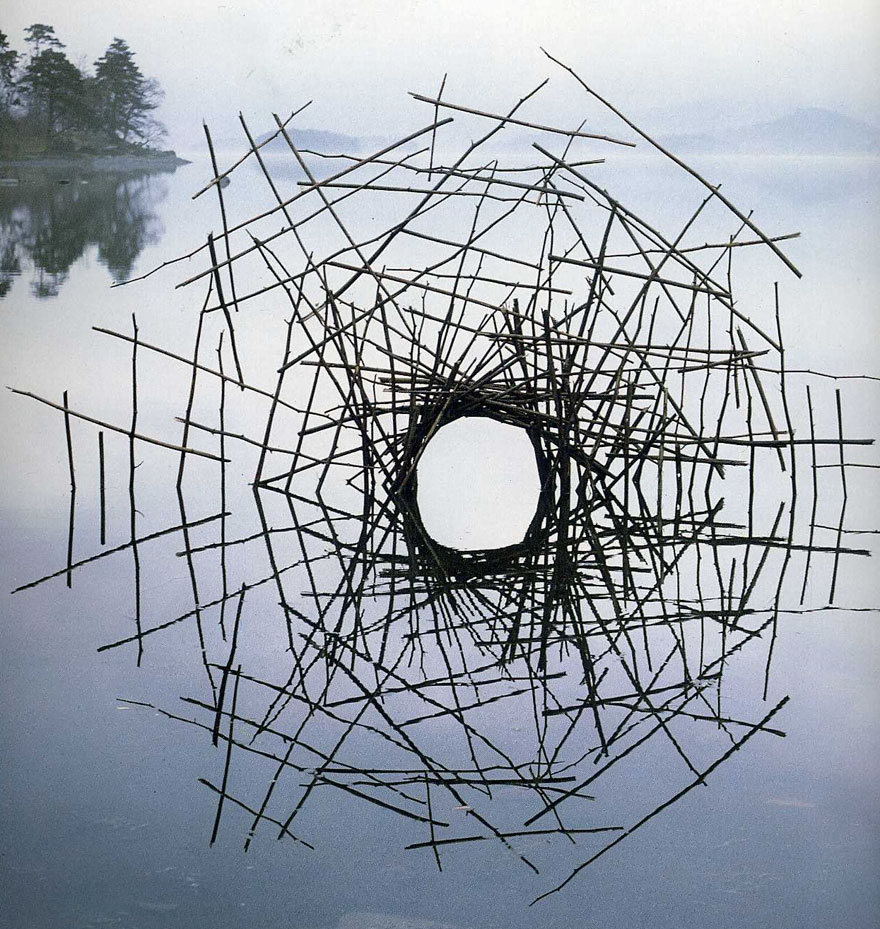

Nils-Udo is a German artist from Bavaria who has been creating environmental art since the 1960s when he moved away from painting and the studio and began to work with, and in, nature. He began as a painter on traditional surfaces, in Paris, but moved to his home country and started to plant creations, putting them in nature’s hands to develop, and eventually disappear. As his work became more ephemeral, Udo introduced photography as part of his art to document and share it. The artist seeks to offer a mutualist vision wherein nature as environment is an omnipresent backdrop. In revealing the diversity in a specific environment, he establishes links between human and natural history, between nature and humanity that are always there, yet seldom recognised. Udo uses natural materials, such as sticks, petals, and branches, to create his site-specific installations.

Another forerunner of the movement, Andy Goldsworthy, is a sculptor and photographer whose artworks directly engage with the environment, incorporating natural specimens and found objects into semi-permanent sculptures. Goldsworthy grew up in West Yorkshire, and worked as a farm labourer from an early age, an experience that allowed him to develop an intense awareness of his surroundings and an appreciation for the ephemeral qualities of landscape. While in school, he became familiar with other British artists following a similar environmental doctrine, including Richard Long and Hamish Fulton. Although the physical survival of his sculptures is rarely ensured, Goldsworthy photographs his sites before, during, and after he has created his structures within the landscape, allowing these photographs to serve as permanent records of each piece.

The land art of the 1960s was sometimes reminiscent of much older land works, like the Stonehenge, the Pyramids, Native American mounds, the Nazca Lines in Peru, Carnac stones and Native American burial grounds, and often evoked the spirituality of such archaeological sites. Today, land art continues to be a powerful means by which to engage our imaginations. Contemporary land artist Sonja Hinrichsen examines urban and natural environments through exploration and research. As an artist she feels the responsibility to address subject matters society tends to neglect or deny, particularly adverse impacts to the natural world. Her work manifests in immersive video installations, video performances and interventions in nature. Her participatory land art project Snow Drawings, evocative of geoglyphs in the snow, engages communities worldwide through its numerous iterations.

Feature image: Nils-Udo, Untitled, La Réunion, 1998. © Nils-Udo